Image credit: Mark Thomson / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Scientist by day, nature-lover by weekend – in Alisha Dordi’s hands, stem cells become organoids, and the lab becomes a window into life itself.

Culturing tiny organ-like structures in the lab is just another day in the office for Advanced Research Assistant, Alisha Dordi, at the Wellcome Sanger Institute. An organoid is a tiny, self-organised three-dimensional (3D) tissue culture typically derived from stem cells. It is created to replicate some of the complexity of an organ to provide a window into disease and development.

Forming such a structure requires an advanced lab skill set – from cell culture experience to an understanding of developmental biology – and most importantly, a steady hand. That is where Alisha comes in. Born in Dubai, with a passion for biological sciences, Alisha left home at 18 years old to begin her research journey. Seven years later, she is here at the Sanger Institute, sharing her story about her career, work and latest hiking ventures.

What does a typical day as an Advanced Research Assistant look like?

I joined the Sanger Institute as a Research Assistant in 2022 and was working on experiments involving the gene editing technology, CRISPR-Cas9. I got promoted last year to Advanced Research Assistant, and then this year, I started working on a whole new area of biology – organoids. So, I have switched from 2D cell culture into more 3D cell culture.

The thing I love about my role within Cellular Services is that there is no typical day. Everyday can encompass something entirely differently. So, whether that is working with organoids themselves, taking them through our entire pipeline, which has different stages – from where they start as stem cells to growing them up and differentiating them into organoids, and then handing this over to our research faculty within the scientific programmes. But I also do other things like writing protocols, doing research and development (R&D), and working with faculty on a closer level to understand their desired outcomes for their projects. In particular, we work quite closely with the Cellular Genomics programme at Sanger, so I am constantly in communication with them. We have regular team meetings where we go through updates, look at how we are tracking and how the organoids are developing. We also discuss any R&D we want to do, for example, we have recently done a bit of optimisation on the organoid pipeline. By improving how many cells we use when starting cultures, we have seen much more consistent growth. This has shown us how important it is to have the right cell coverage for both our trophoblast stem cells and placental organoids to grow and develop properly. We have also been working on better freezing methods by trying out different ways to separate the cells, which has helped us maximise cell viability during thawing and improve the overall success of organoid recovery.

Within Cellular Services, we make sure we are implementing the 5S methodology for workplace organisation – Sort, Set in Order, Shine, Standardise and Sustain – to optimise our lab spaces and ensure best practice. We also work with the LEAF programme, which sets a standard to improve the sustainability and efficiency of labs. We are currently at bronze status. I am keen to get involved in things like this outside of my usual projects. It is a nice balance between doing lab work and just being a more active member of the team.

As my team sits in operations, I very much enjoy the variety within our projects as I get to work with different programmes. We are in the centre of how these projects are run. Our team will typically take ideas from the programme faculty and run them at high scale.

For example, last year I worked with Senior Group Leader and Interim Head of Cancer, Ageing and Somatic Mutations programme, Dr Dave Adams, on a CRISPR screening project. His team were looking at knocking out tumour suppressor genes within cells, seeing how they impacted cancer development and identifying synthetic lethal targets. These targets are genes or pathways where simultaneous inhibition or loss causes cell death, while inhibition of either alone does not. We were involved in scaling this project up to run more tests.

I am also fortunate enough to have worked with other teams outside of the programmes, including science engagement, the automation team and the sequencing labs – I am basically at the centre of a lot of different types of work, which I like.

Have you always wanted to be a scientific researcher?

I actually wanted to be a marine biologist growing up, but that ended very quickly, because I am terrified of the ocean. As soon as I found out that you have to be in the field to be a good marine biologist, my dream ended very quickly. But I have always known that I wanted to do something in the biomedical research field.

Alisha Dordi working with organoid cultures. Image credit: Mark Thomson / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

How did you end up here at Sanger? What was your journey to get here?

Seven years ago, I came to the UK from Dubai and went to the University of Birmingham to do an undergraduate degree in Biological Sciences. I did that for three years and really enjoyed it. As I said, I always knew I wanted to go into something biology related, but at that point, I was too young to know what I wanted to do specifically. Toward my final year, I specialised in genetics and was particularly interested in cancer. It interested me so much that I decided to stay at the University of Birmingham and complete my Master of Research in Cancer Sciences. This was a programme that was specifically designed for people who were really interested in the research field but also wanted to go into something cancer biology related in the future. It was a bit different to a normal master’s in science, because it had the research element to it. I was placed in a lab for eight months, and I was given my own project to do. I was thrown in at the deep end a little bit; it is very similar to the first year of a PhD.

The eight-month placement I did in this lab provided me with all the skills I needed to get my job at Sanger. I finished my master’s in 2022 and then in the winter of 2022 I joined Sanger as a Research Assistant. So, I moved from Birmingham to Cambridge.

What was it like moving from Dubai to the UK?

It was a bit of a culture shock. In Dubai, the schooling is very specific – you are able to choose whatever school you go for. Funnily enough, I did the Cambridge International examinations, which is a British curriculum, so the type of schooling I got was very similar to what people get in the UK.

However, there was definitely a shift in moving from there to here. I think here is generally more freeing for me; I have got to be more independent. I sometimes miss the luxury of Dubai, and it is a very safe city too. Also, all my family are still there so I do get homesick. I think every international student experiences this. This was probably the hardest thing about moving and I was quite young when I moved across the world. But most of the genetic research is happening in the UK or USA, so for the work I want to do and how I want to contribute to it, this is the perfect place for me right now.

Can you tell us about your latest research project?

I am working on a project in collaboration with Dr Roser Vento-Tormo’s group in Cellular Genomics. Her team are focused on learning all they can about the female reproductive system. The project I am working on is called TrophoSphere, which is looking into how the placenta works and develops during pregnancy. In the lab, this translates to creating placental organoids, which are really good biological models for studying how the placenta works, how it grows, how it interacts during a healthy versus unhealthy pregnancy and what those differences are. For example, expecting mothers can get preeclampsia, which causes symptoms like high blood pressure, and can be fatal. Others can also get sudden miscarriages. Reproductive diseases are generally not well understood; there are a lot of unknowns – which is what Roser’s team want to change.

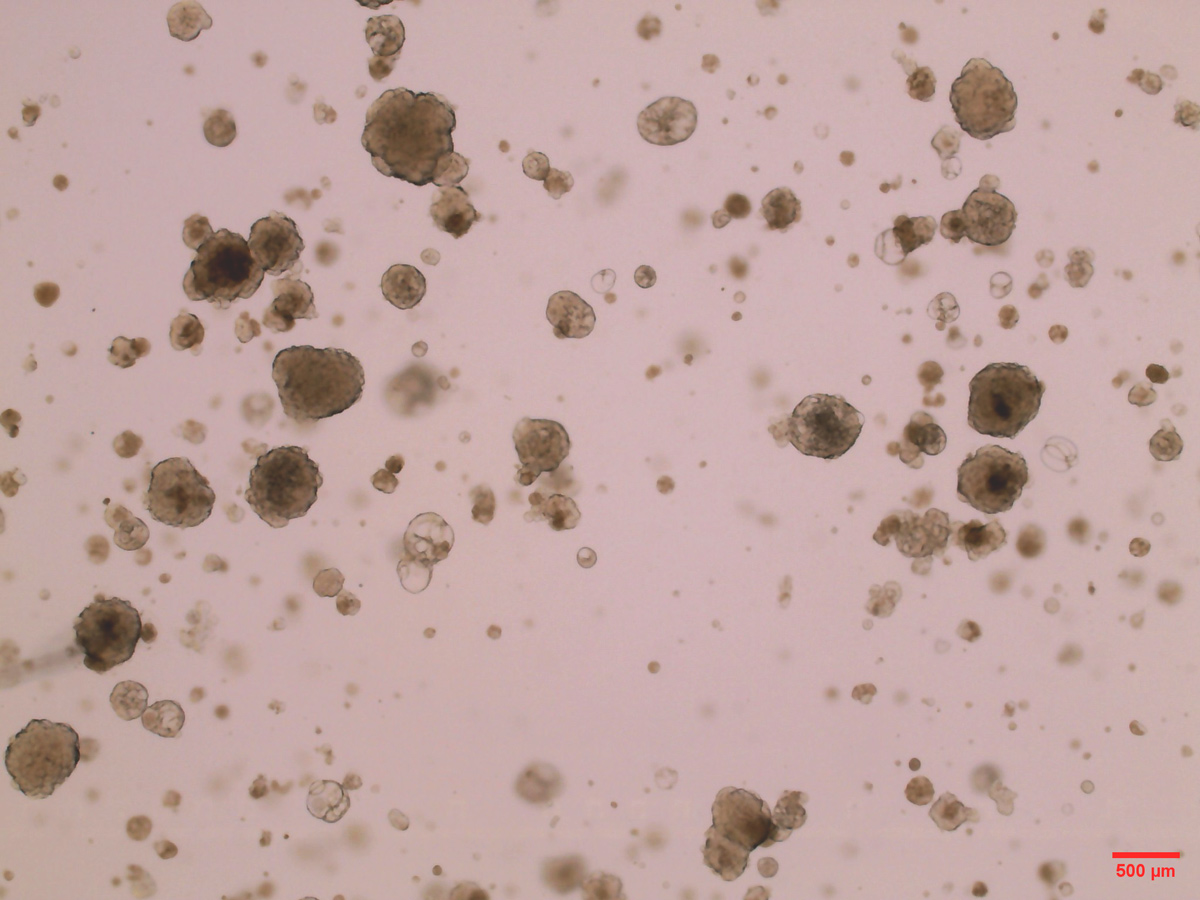

Organoids are relatively new in the field. They are tiny, simplified, 3D structures grown in the lab that mimic organs in the actual human body. So not only are they good for us, but they are also good in the sense that we do not have to rely on animal models as much anymore.

TrophoSphere specifically focuses on growing and differentiating placental organoids. We culture human trophoblast stem cells using well-characterised cell lines which are derived from first-trimester placental tissue. These stem cells are expanded under defined conditions before being introduced into 3D culture systems, where they self-organise into organoids that model key aspects of early placental development.

From left to right: Trophoblast stem cells, placental organoids after differentiation, and placental organoids before differentiation. Image credit: Alisha Dordi / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

When pregnancy happens, you essentially get fusion of the fertilised egg into the endometrium – the inner lining of the uterus; this is how it implants. Sometimes that does not happen very well, for example, the fertilised egg will not implant enough, in which case you may get miscarriages. Sometimes it happens a bit too well and the egg goes a bit too deep into the endometrium, in which case it may cause preeclampsia.

So, it is just about understanding how these things work, what metabolites are involved, what genes regulate it, and that sort of thing. We are trying to grow these placental organoids to mimic that process.

What has been the most rewarding and hardest parts of your work?

I think the most rewarding thing is getting to work with different projects. I transitioned into working with organoids at the start of this year, so I am relatively new to the field. I have learned so much in the last six months, not just about placental organoids specifically, but organoids in general.

When I worked with CRISPR screening and 2D cancer cells, that gave me a whole range of exposure. But then I expressed that I wanted to learn more about the models that were coming up in research, the ones that could potentially be more useful for personalised medicine and gene editing techniques. So, with the help of my manager and team, I got into organoid research.

"The most exciting thing is just being able to learn on the job as I go, it is quite flexible; you can work on a range of projects, and just learn new things."

Alisha Dordi,

Advanced Research Assistant, Wellcome Sanger Institute

Another rewarding element of my job is when experiments go to plan from start to finish, which they do not always do. You get a sense of satisfaction that you are doing something right. I am also quite excited about the future implications of the placental organoid work, because we are trying to understand such a niche thing that not many people in the world have successfully researched – it is quite amazing that we can do that in our labs.

The hardest thing is probably when things just do not work out in experiments, and you do not know why. So, we have had instances where we cannot pinpoint a specific reason as to why the cells do not grow. It might not even be a single cause, it might be a variety of causes, in which case we have to go back to the drawing board and talk with faculty. We then have to do R&D work to find out what has gone wrong and even then, sometimes we do not always get an answer, and we just have to accept it.

How do you continue learning and developing as a scientist?

I love attending conferences, so when I transitioned into working with organoids at the start of this year, I knew very little. I have obviously heard of them and wanted to work with them, but at a base level, I was just a beginner.

So, there was a really good opportunity at the start of the year where we got to attend the World Organoid Research Day, which Sanger hosted at the conference centre on the Wellcome Genome Campus. This day introduced me into the field, it helped me network and see the different types of organoid research going on across Europe.

I think there are also so many seminars and talks that go on every week at the Institute, from different faculty groups, different operations teams, etc. I like going as much as I can so I can learn different things. We also have monthly meetings within the team where people share their results and introduce the different projects they are working on. I also really like presenting posters myself at conferences – I think they are a really good way to spread knowledge.

What are your plans for the future?

I would like to bring together my previous experience working with CRISPR and my current work with organoids to explore new ways of studying human development and disease. While I am not currently working with cancer organoids, I believe the potential of this technology goes far beyond oncology. Organoids – whether placental, intestinal, brain or otherwise – offer a powerful, adaptable platform for gene editing. By applying CRISPR to these models, we can begin to ask precise biological questions, explore gene function and even mimic disease mutations in a controlled environment. Ultimately, I would love to contribute to building accurate, gene-edited organoid models for a wide range of diseases – each one tailored to better reflect human biology and improve our ability to understand, prevent or treat illness.

Alisha Dordi looking at organoids under a light microscope in the lab. Image credit: Mark Thomson / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Has there been anyone or a group of people that have shaped your career?

I would say Dr Felicity de Cogan’s lab where I did my master’s in Birmingham. The team – the postdocs, research assistants, students and my supervisor – helped me grow so much as a scientist. I would really recommend people do a Master of Research because it was such a pivotal moment in my career. I really learned everything about cell culture, working in a sterile environment, working with chemicals, the hazards of working in a lab – everything about being a lab scientist. It really helped me to realise how much I love research and remove any hesitations I had about pursuing a career in science. It is natural to wonder whether you are making the right decision, and I had a lot of imposter syndrome at the time. But this opportunity really reaffirmed that I was making the right decision.

What advice would you give to individuals considering a similar path?

This might seem a bit obvious, but I would say: just ask questions to people – ask your lecturers and ask your peers.

I also think if you get the opportunity, try to gain practical experience in the lab. Having that experience will embed those skills before you even start a job – like it did for me. I would say this experience really helped me get the job at Sanger. Even if you do not want to pursue that route, trying it will make you quickly realise whether you want to be a dry lab scientist instead, for example, focussing on computational work. I just think learning practically is really important.

"Also, stay curious and opened minded. These are the things that have worked best for me."

Alisha Dordi,

Advanced Research Assistant, Wellcome Sanger Institute

What do you like to do in your spare time?

I like being outdoors. I try my best to go on walks – I would like to attempt climbing Mount Snowdon next year.

I listen to a lot of podcasts – I really like the New Scientist one. I recently listened to one about brain organoids and how in the future they might be used to power microchips, which I thought was really interesting.

I like reading; I would recommend my latest book, Yellowface – that was really good. The last science book I read was Sapiens and that is probably my favourite – it is about human evolution.