Image credit: Carmen Denman Hume / Wellcome Sanger Institute

The basement. The setting for every horror movie. While we all shout at the main character to not go down there to inspect the strange noise, sometimes it is all too enticing.

At the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the basement noise is a combination of spinning sounds, clicking and humming – and Craig David playing on the radio. This is where Colin Barker’s workshop is and the hub of some very exciting engineering projects.

Listen to this blog:

Listen to "Basement builds that are shaping our research" on Spreaker.

Colin is a trained engineer. After completing his GCSEs, he got his first job working on mining lamps. He later went on to do an apprenticeship and became one of the first people to create carbon fibre moulds for helicopter blades.

Now, Colin has been working at the Sanger Institute for 23 years, solving researchers’ problems and innovating to streamline their work. We caught up with Colin in his workshop to discuss some of his latest projects.

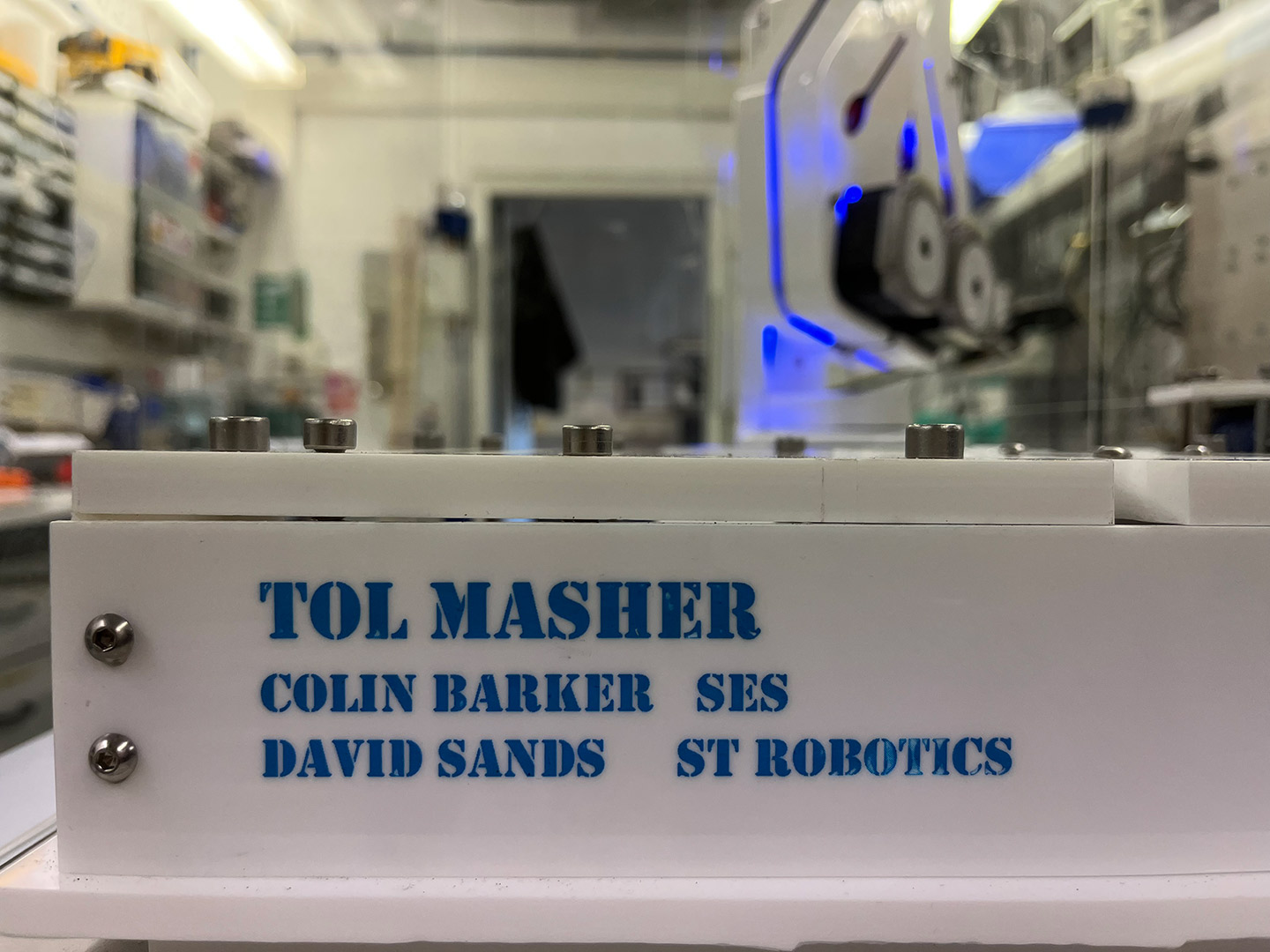

Tree of Life masher

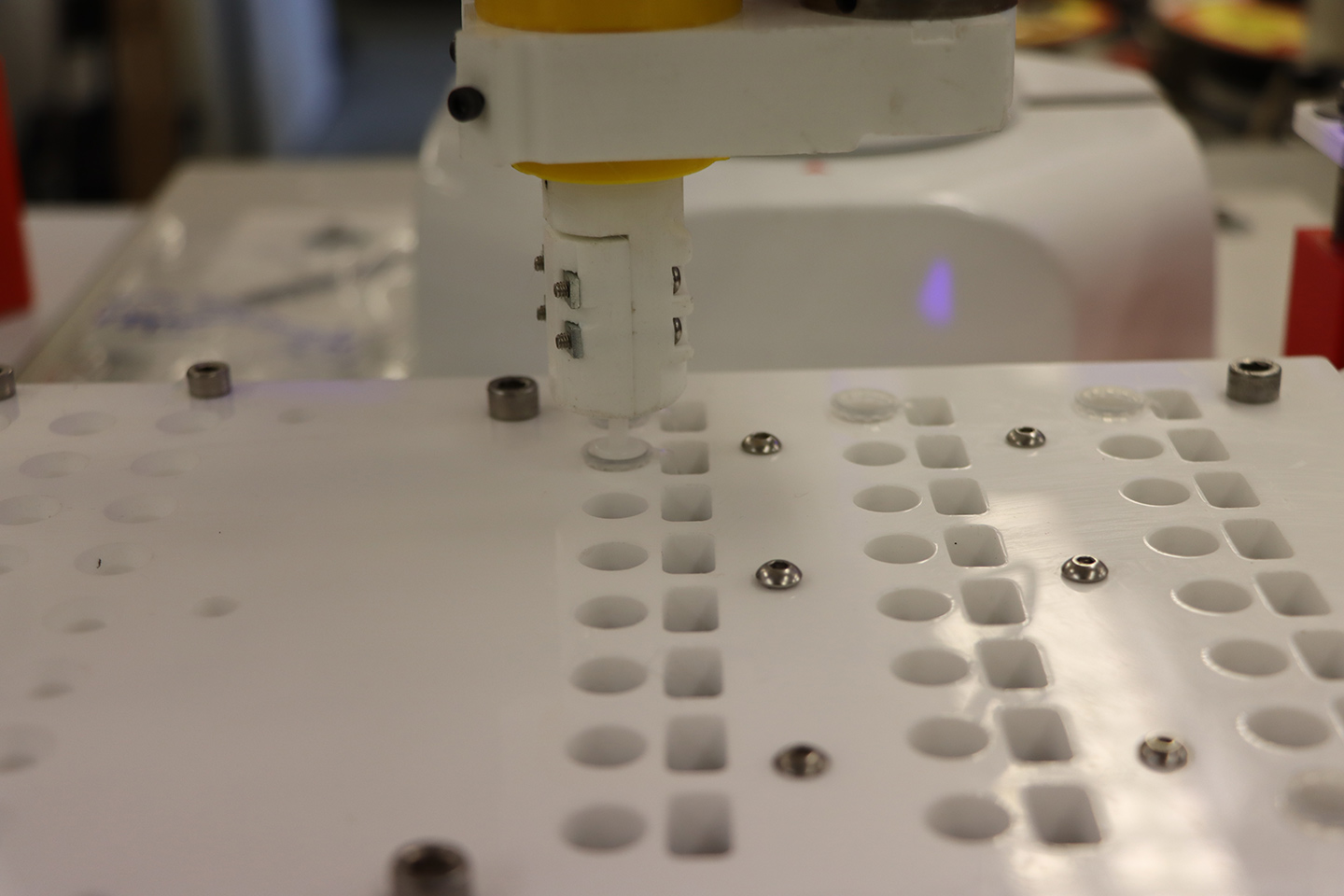

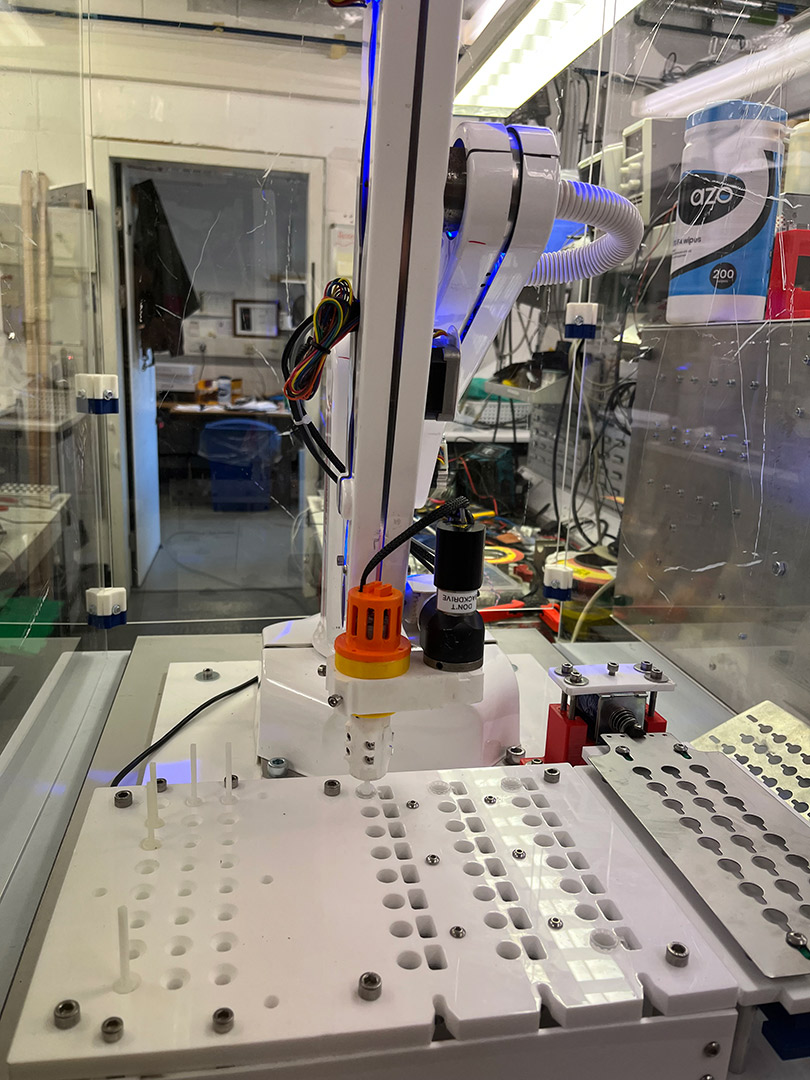

The Tree of Life programme at the Institute is working to investigate the diversity and origins of life on Earth. In a video, published on our social media accounts in 2022, Colin heard all about this work and stumbled upon a clip of a researcher manually mashing their sample with a small tool, called a BioMasher, to release the genetic material. This inspired him to see if he could automate it.

Flash forward to 2025, and Colin is building a robot to run this very process. To do this, he has used an old robot and created other key components using a 3D printer. The robot arm is linked up to a computer that controls the process. It begins by picking up a fresh pestle head that mimics the BioMasher. It then moves into the first well and starts to break up the sample, exactly like what would be done manually. The number of times this is done is controllable via the computer. Once the sample has been broken up, the arm moves and loads the attached piece into a different empty well. Colin has set the robot up so that it goes around the wells to avoid contamination.

The current prototype aligns with the first three lines of a 96-well plate. While this would previously take a whole morning to do manually, Colin’s invention takes around 50 minutes. His next goal is to create reusable attachment pieces that mash the sample in order to reduce waste.

Tree of Life Masher: Clockwise from top left to bottom left - The masher was designed and built by Colin and David Sands, Colin testing the masher robot in his workshop, the masher at work in an eppendorf tube, the 'recycled' robot arm, the computer and software that run the robot masher, the specially designed and 3D printed mechanism of the pestle and mortar.

Stepping image camera for BIOSCAN

The BIOSCAN project is a part of the Tree of Life programme and aims to study the genetic diversity of one million flying insects from across the UK. Samples are collected by researchers from the Institute as well as from UK collaborators and are put into 96-well plates. One insect goes into each well along with ethanol to preserve the sample. Before sequencing begins, researchers must identify the insect in the well.

To support with this process, Colin has developed a contraption that enables imaging of each well in the plate. The camera goes down into the well and takes staggered images at different heights. After this, all focussed images are then made into one clear image for identification. Colin has mounted LED lights to ensure that the light is correctly angled into the ethanol to avoid reflection. A light is also at the bottom to help illuminate darker specimens. The team are already using the imager and will continue to tweak and improve its functionality as they go on.

This new imager, built from old robots that were no longer being used by the Institute, provides improved quality compared to previous imagers. Before, the BIOSCAN team could just about tell what order – fly, wasp, beetle, etc. – each specimen was. Now, they can identify clearly the order for every specimen, family level for many and even genus or species for some.

Evolution of the BIOSCAN automated imager. From left to right: Prototype with both the camera set up and its holding mechanism 3D printed, testing the holders with the real camera, testing optimal lighting set up, seeing the results of automated image capture.

Plate desealer

Plate desealer.

When samples arrive at the Sanger Institute in 96-well plates, researchers have to gently remove the tight seal, which is put in place to avoid evaporation and contamination during transport. However, the removal of the seal can prove challenging for researchers and can actually result in spills and contamination.

To get around this, Colin previously developed a flat, rigid board to stabilise the plate when removing the seal. The board can be screwed to a researcher’s work bench and then the plate securely inserted inside. This allows them to pull the seal off easily with two hands. This is now a standard product around the world and circumvents the cost barriers associated with more advanced machines that punch through the seals.

Bead dispenser

Bead beating is a method used by researchers to disrupt biological samples by shaking them with beads in a specialised device. Getting a specific number of beads into each separate tube is a very laborious and manual process, but necessary for standardisation across samples.

To streamline this process, Colin has created a ‘pin ball’ like machine that allows researchers to put all of their beads onto a surface and then shake them until they drop into small wells within the surface. Each well only allows a certain number of beads in it, depending on what is needed, and can be adjusted for different requirements. This process is fast and efficient – and dare I say fun.

Bead dispenser: From left to right: the mechanism to release the beads, the full bead dispenser and tube holder, Colin displaying the inside of the tube holder.

3D-printed lab tools

Colin is a master of 3D printing. He has a whole room of different types of machines, with different functions – all of which he uses for some small but useful tools for the lab. He first uses a computer-aided design (CAD) program to create 2D and 3D models of his creations. This allows him to fine tune the measurements and shapes of his objects.

For example, every lab has a few yellow Bio-bins that are used for the disposal of non-sharp waste. These bins are made of paper and therefore, are prone to falling over. Stainless steel stands to hold these up can be a bit costly and as such, Colin decided to create his very own stands all from scrap acrylic.

3D printed tools. Clockwise from top left to bottom left: Collection of different-sized jar openers, bespoke falcon tube holders with a Stars Wars twist, acrylic Bio-bin stand, 3D printed jar opener.

Other 3D-printed tools Colin has created include stands for tubes and conical flasks that are not available on the market. These are always seen in our labs at Sanger to improve organisation and support the tubes that are being used. But while most of Colin’s designs follow the standard format, he also ensures that he showcases his creative flare in his work by designing a stand for falcon tubes that mimics the Millennium Falcon starship from the Star Wars franchise.

Another useful invention of Colins, is a number of different jar openers. Our researchers work with a lot of different chemicals, some of which are even harder to open than that jar of jam at the back of your cupboard. These openers make it easier for researchers to conduct their work and also reduces the repetitive pressure on people’s wrists.

Colin creating solutions in his workshop. From left to right: Colin with a freshly-printed bespoke tube holder, Colin with the workshop's 3D printers, Colin designing his solutions for 3D printing.

Unlike the people in horror movies, visiting Colin’s workshop is like stepping into Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. It contains a series of inventions that most people wouldn’t think to create, but when in action, can make lives and research so much easier and more cost effective.

“I never make anything the same twice. Every time I test something, I refine it. I want to make it better than the version before. Even in a short period of time, I enjoy finding ways to improve the creations I have made. Whether something becomes more compact or has improved features, it is my job to make the product fit for long-term use. It is interesting to see how many things I have made that I would personally deem simple, but to other people, they make such a big difference to their day-to-day work.”

Colin Barker,

Scientific Instrument Maker, Wellcome Sanger Institute