Image credit: Luke Lythgoe / Wellcome Sanger Institute

As temperatures plummet this winter in the Northern Hemisphere, we found ourselves wondering what are the weirdest and quirkiest things currently stored in the Wellcome Sanger Institute’s freezers?

Walk to your kitchen and open the freezer door; what is the weirdest thing you will find? Ancient frozen vegetables that have followed you from one house to the next? Unlabelled plastic containers with a mystery gloop inside, or maybe a few frozen berries that have escaped their packaging.

At the Wellcome Sanger Institute, where we sequence samples from tumours to toads, and pretty much everything in between, there are a fair few weirder – but still wonderful – frozen samples waiting for their DNA to be studied.

In this blog, we have compiled some of the quirkiest characters currently queuing in deep freeze.

1. Giant deep-sea creatures

When it comes to species of large, scary-looking creatures from the deep, we highly rate giant deep-sea isopods of the genus Bathynomus, some of which can grow up to half a metre long!

Giant deep-sea isopods are crustaceans, as are their relatives, the terrestrial isopods. More commonly known as woodlice or pill-bugs, you can find isopods under plant pots in your back garden.

Bathynomus doederleinii is a smaller 'giant' deep-sea isopod – compared to the super giants – and is typically only found in waters around the Asian continent.

Dr Jess Thomas Thorpe, Janet Thornton Postdoctoral Fellow in the Sanger Institute’s Tree of Life programme, studies the genomes of different isopods to understand how this order of crustaceans has successfully adapted to so many different environments around the world.

Isopods live in lots of places, from polar regions to tropical waters, freshwater environments such as ponds and subterranean aquifers – they have even been found at high altitudes! These critters are not picky; they will colonise pretty much anywhere.

Jess’ ongoing research involves trying to understand how isopod evolution occurred. She is actively collecting samples from all over the world in order to diversify the species and genomes available to researchers studying isopod evolution. Jess and her research contribute to the Darwin Tree of Life project, the effort to sequence all life on the British Isles, which you can read more about in this recent Marine Biological Association article.

2. Plenty of poo

Who knew that studying the waste product of species could illuminate so much about their wellbeing? Sanger freezers are filled with stool samples from all over the world. In fact, it was hard to choose which stool samples to scintillate our audiences with.

It is a wormy world out there, so it should come as no surprise that members of the Institute’s Parasites and Microbes and Tree of Life programmes have freezers filled with interesting artefacts.

Career Development Fellow, Dr Steve Doyle leads a group that studies parasitic worms that infect both humans and other animals. Steve is currently part of a collaboration called STOP2030, which aims to evaluate a combination therapy of two commonly used anthelmintic drugs in order to improve the treatment of soil-transmitted helminths afflicting over a billion people worldwide. Steve’s group is focused on understanding the genetic responses to drug treatment by parasitic worms and monitoring the emergence of their drug resistance.

Most of the species that Steve and his team study live in the guts of their host, and so the best way to collect the worms is via stool sampling.

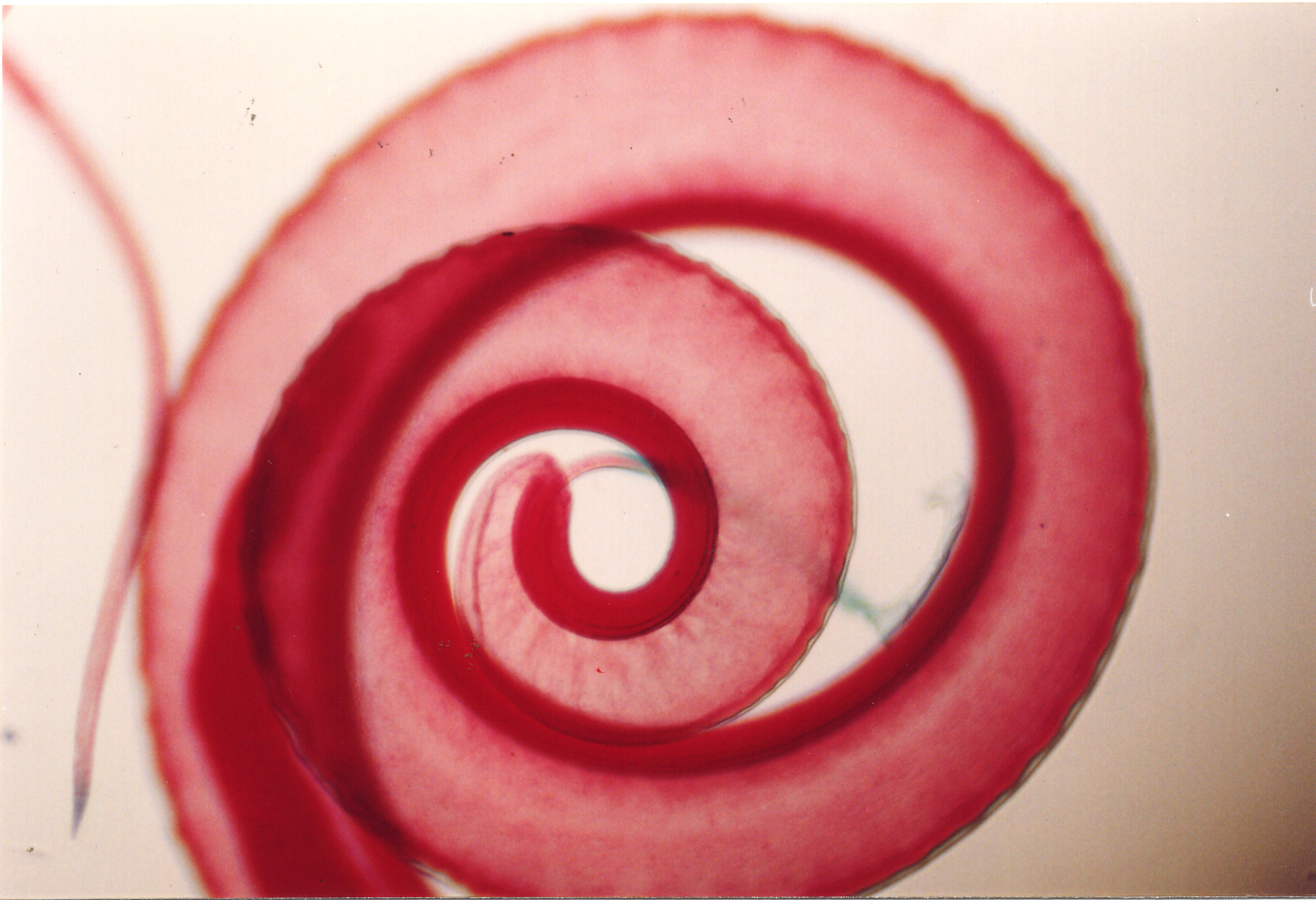

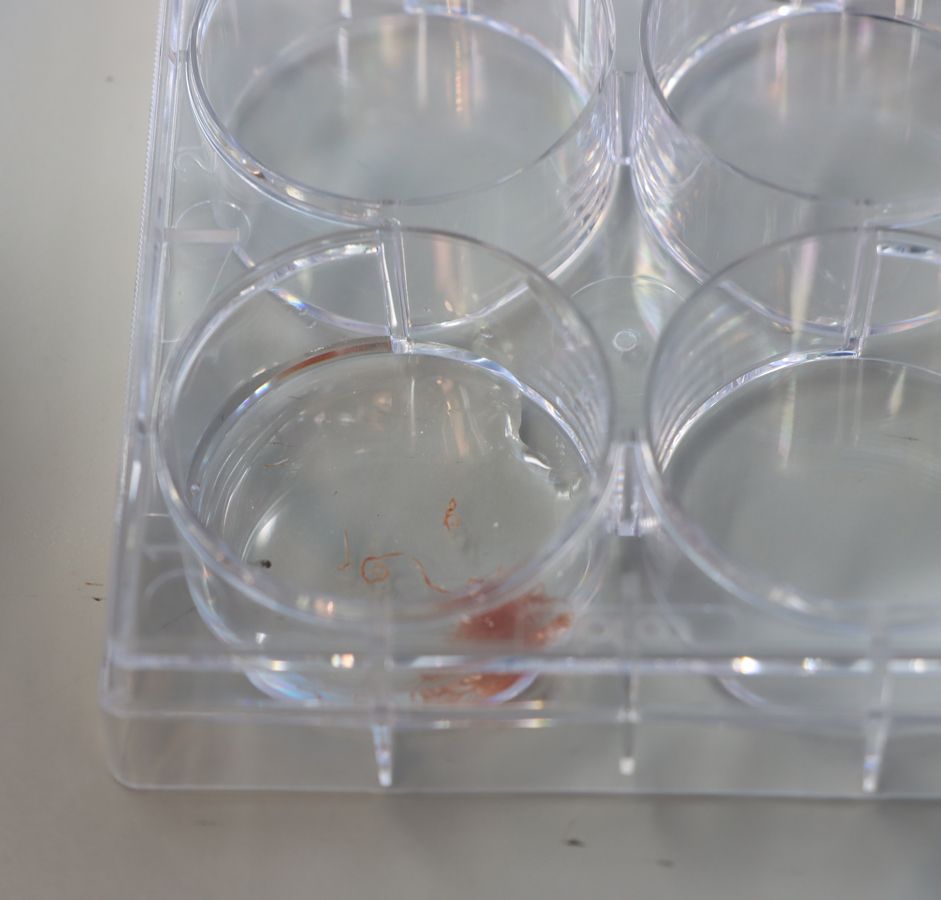

The samples in the Doyle lab freezers contain different species of worms, such as samples of Trichuris trichiura, more commonly known as the whipworm.

Trichuris trichiura up close and personal. First photo: a male worm seen through a light microscope. Second photo: High-resolution image using scanning electron microscopy. Image credits: Punlop Anusonpornperm / Wikimedia Commons and Dave Goulding / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Whipworms cause significant global health issues, affecting more than 500 million people, particularly individuals in low- and middle-income countries. Steve’s group leverages genomic insights to improve treatments, interventions, and public health policies.

You can read more about worms in Steve’s research labs in this blog.

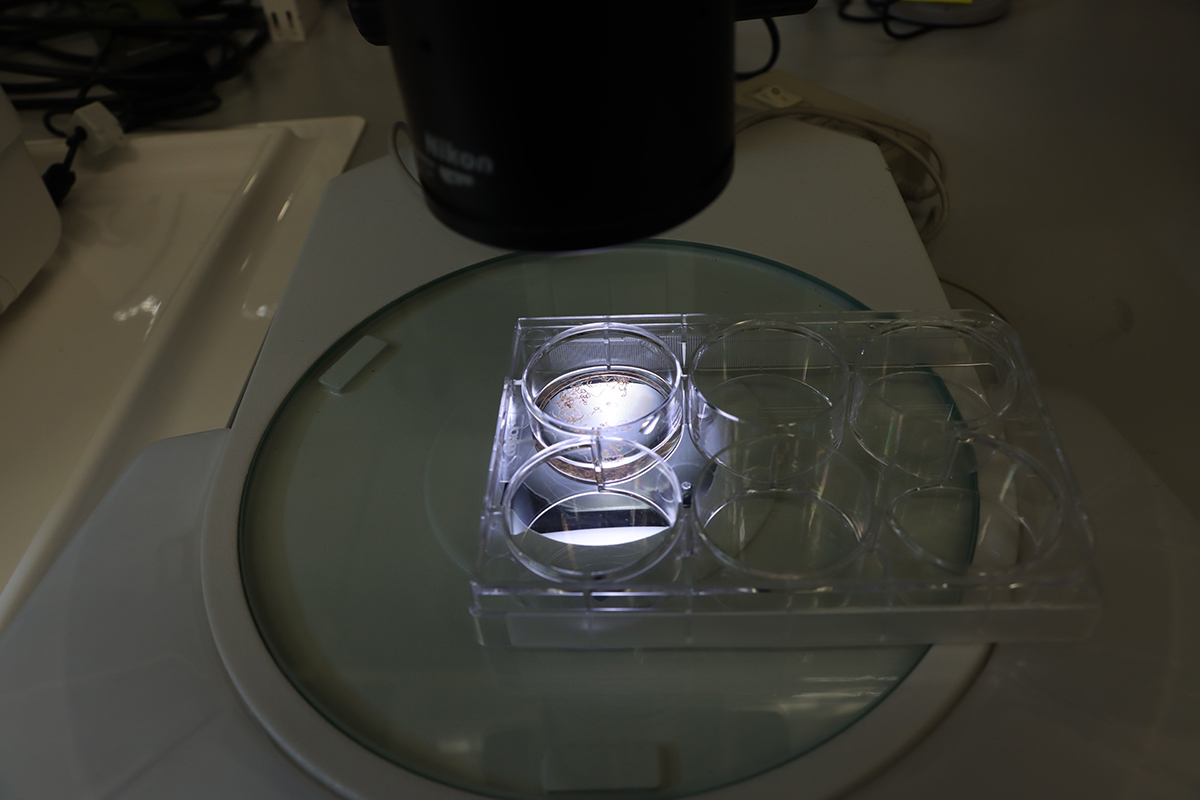

Not to be outwriggled, but Dr Lewis Stevens, Postdoctoral Researcher in the Tree of Life programme, also studies parasitic worms. Lewis is a nematode expert and is set on devising tools to make studying worms easier and create a more diverse database of nematode genomes.

Studying nematode genomes reveals how they survive, spread, and cause disease, but current approaches involve dissecting dead hosts to retrieve adult parasites.

Lewis hopes to develop new methods that make parasite genetics easier by adapting methods for juvenile parasites. Why? The juvenile parasites can be easily obtained from the faeces of infected hosts.

Some of the sheep that have contributed to Dr Lewis Stevens' research. Images credit: Martin Stoffel.

Lewis has poo samples collected and frozen from wild sheep that live on a remote Scottish island. His hope is to reconstruct the genomes of the most common parasite species and identify the genetic differences between individual parasites. If successful, this new approach will make it much easier to study the genomes of parasites and explore how they cause disease.

3. Testes – yes, you read that right

Flies can transmit their genes in surprisingly unusual ways. Dark-winged fungus gnats are a striking example, carrying an entire set of chromosomes that exist only in the germline. Germline-specific DNA is the genetic material found in reproductive cells (eggs and sperm).

Dr Kamil Jaron, Group Leader in the Sanger Institute’s Tree of Life programme, explores the genetic inheritance of these germline chromosomes by sequencing reference genomes using a single pair of fly testes.

Dark-winged fungus gnats have DNA in their sperm and eggs that is not found in the rest of their bodies. Image credits: Robert Webster xpda.com / Wikimedia Commons and Mike Pennington / Wikimedia Commons.

Dr Aleksandra ‘Sasha’ Bliznina, postdoctoral fellow in Kamil’s group, pioneered the approach to study evolution via germline chromosome sequencing of individual fly testes.

This approach has unlocked new information found in hundreds of fly species that live around us; yet we do not know how to cultivate them (except of the few pesky species found in flowerpots).

What kind of role these genes play in the biology of species and how they have survived in the fly germline for tens of millions of years is a mystery researchers are trying to solve.

Kamil and Sasha are keen to study organisms that reproduce their genomes in unusual ways. By examining species with unconventional modes of genetic inheritance – and crucially doing so at scale through the Tree of Life Genome Production pipeline – they aim to uncover new principles governing how genetic information is passed between generations. You can read more about research in Kamil’s group in this blog.

4. Naked mole rats

In the Sanger Institute’s Somatic Genomics programme, naked mole rat testes and colon are also commonly found in the freezers. This subterranean species is never really active above ground, has poor eyesight, and bare skin. Yet, naked mole rats have exceptionally long lifespans compared to other rodent species.

Researchers led by Group Leader, Dr Jyoti Nangalia, hope to figure out why naked mole rats can ‘defy’ ageing by analysing somatic mutation patterns in their different tissues: blood, colon and testes.

PhD student Riley Jung, who works in Jyoti’s group, studies these tissues to investigate the peculiarities in the naked mole rats' somatic mutation landscape. Riley hopes to learn how such information could help mitigate age-related diseases in humans.

5. Tiger, giraffe and shark

As part of a project to compare somatic evolution across species, Group Leader, Dr Inigo Martincorena and collaborator, Dr Alex Cagan, Group Leader at the University of Cambridge, have collected a wide range of samples. They are trying to understand how somatic mutations accumulate over the lifespan of organisms, and how this process relates to ageing and cancer risk across species.

Using colon samples from 16 mammalian species, their work – published in 2022 – provided the first experimental evidence for an inverse relationship between species lifespan and somatic mutation rate. This showed that short-lived species accumulate mutations far more rapidly per year than long-lived ones, yet often reach a similar total number of mutations by the end of life.

These findings support the idea that longer-lived species have evolved enhanced DNA maintenance mechanisms that ‘fix’ mutations, helping explain cancer resistance in animals such as whales and elephants.

Now, Inigo and Alex are expanding this approach beyond mammals and beyond the colon, using ultra-accurate sequencing methods – such as NanoSeq – to study multiple tissues and species. Through collaborations with London Zoo, the UK Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme and other expert groups, they hope to uncover how different organisms protect their genomes, how these mechanisms shape ageing and cancer susceptibility, and whether insights from evolution can inform healthier human ageing and cancer prevention.

Next time you wander towards your deep freeze for dinner prospects, consider yourself lucky that you are not dodging poop, whale tissue, or worms to get your grub on.

At the very least, perhaps it is time to defrost your own freezer and start fresh for 2026, with fewer rogue blueberries rolling out the door.