Image credit: Kelly Sikkema / Unsplash

It is that time of year – the heated blanket is plugged in, the car de-icer is at the ready and the box of tissues is purchased in preparation for an impending cold. But for many, flu season has come earlier this year with hospitalisations rising by more than 50 per cent in one week.1 The so-called ‘super flu’ is causing a media frenzy – but what actually is it? Why are we seeing it earlier than usual? And how can we be better prepared in the future?

We caught up with Wellcome Sanger Institute’s Dr Ewan Harrison, Head of the Respiratory Virus and Microbiome Initiative, and Postdoctoral Fellow, Dr Marissa Knoll, from the Parasite and Microbes programme to unpack these questions further. From how the flu virus works to how vaccines protect us, they share how their research tracking respiratory viruses in healthcare workers with the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) could help us stay one step ahead.

What is the so-called ‘super flu’?

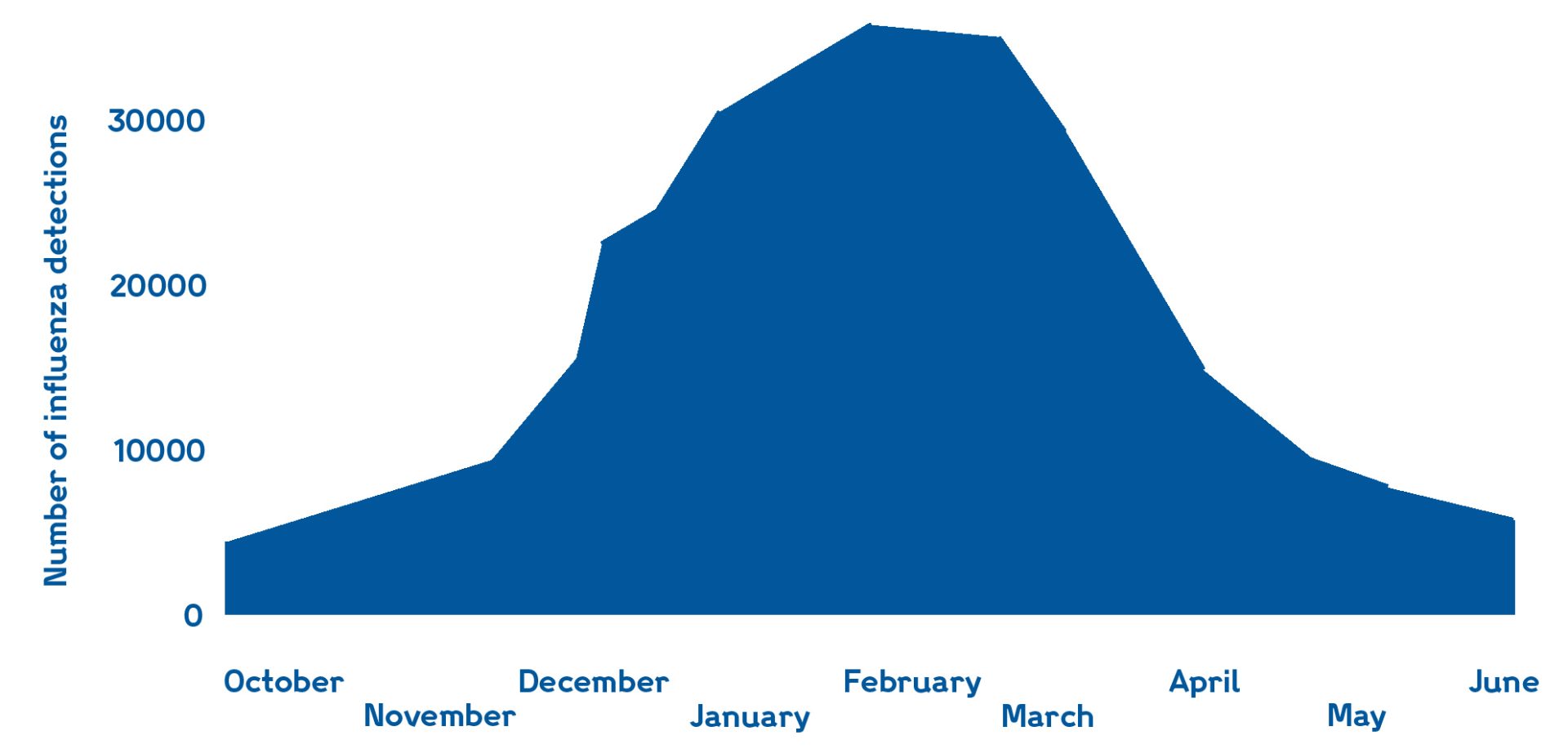

Media outlets are terming the latest influx of flu cases as the ‘super flu’ – but in fact, it is simply just the flu. Flu is a seasonal virus – every year, you see a clear spike in the emergence of flu cases during the winter season. There are several reasons for this, including the ability of influenza and other respiratory viruses to survive longer and transmit more efficiently in cold, dry air, increased time spent indoors socialising and seasonal variation in host immune responses. Flu predominantly impacts older adults, children and those with preexisting health conditions as their immune systems are typically less likely to be able to control infection and handle its consequences. This is why vaccine recommendations are targeted at these groups.

Seasonality of flu cases in the northern hemisphere, with the height over the winter season. Adapted from World Health Organisation (WHO) report.

Every year, there are three main variants and subtypes of flu that circulate seasonally within human populations: influenza A subtypes H1N1 and H3N2, and influenza B – the latter is often less likely to be the main cause of disease. H1N1 and H3N2 usually co-circulate together but one tends to dominate each season. This winter in the northern hemisphere, H3N2 is dominating – but this time, earlier than expected. This year we are seeing a variant of the H3N2 virus known as sub clade K. This variant has alterations in the protein that binds to human cells to cause infection.

“It is likely that we are seeing an increase in cases because the sub clade K variant of H3N2 has an advantage that makes it more effective at causing infections compared to other strains of influenza currently circulating in the human population,” explains Marissa.

What effect does the vaccine have on the ‘super flu’?

Another reason why we are seeing an increase in cases is the fact that the variant is not as well matched to the H3N2 that is in the current flu vaccine. Each year, the flu vaccine is developed based on what viruses are circulating roughly six months prior in addition to forward modelling. The benefit of the northern and southern hemispheres having winters at different times of the year, means that researchers can use data from previous flu samples to try and predict what might be circulating in the other hemisphere when winter arrives. Experts use this information and mathematical modelling to determine the likely direction of evolution from the population that they have. They then try to account for this when the World Health Organization makes their recommendations for what strain of those three different influenza viruses should go in the next vaccine.

There are many online comments from people who say they have never had the flu vaccine and seem to be fine. This is true of many aspects of life: some people can be exposed to infections or other illnesses and experience little to no impact, while others seem to be more susceptible. That variability is precisely why public health recommendations focus on protecting those who are most vulnerable.

The flu vaccine is still essential for people at high risk and their caregivers. While there may be slight genetic differences between the virus in the vaccine and the one that is circulating, the vaccine still provides protection against severe disease.2 Importantly, there is also currently no evidence to suggest that the virus is evading the protection from this year’s vaccine; estimates suggest it may be slightly more transmissible, but the evidence is not strong enough yet to say this with certainty.3 Therefore, vaccination is still important for protecting against severe illness.

How can we better understand respiratory viruses?

Just as we learned with SARS-CoV-2, understanding more about viruses can enable us to be better prepared. “If we had understood more about the evolution and biology of seasonal coronaviruses, we would have likely been better equipped to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic,” notes Ewan.

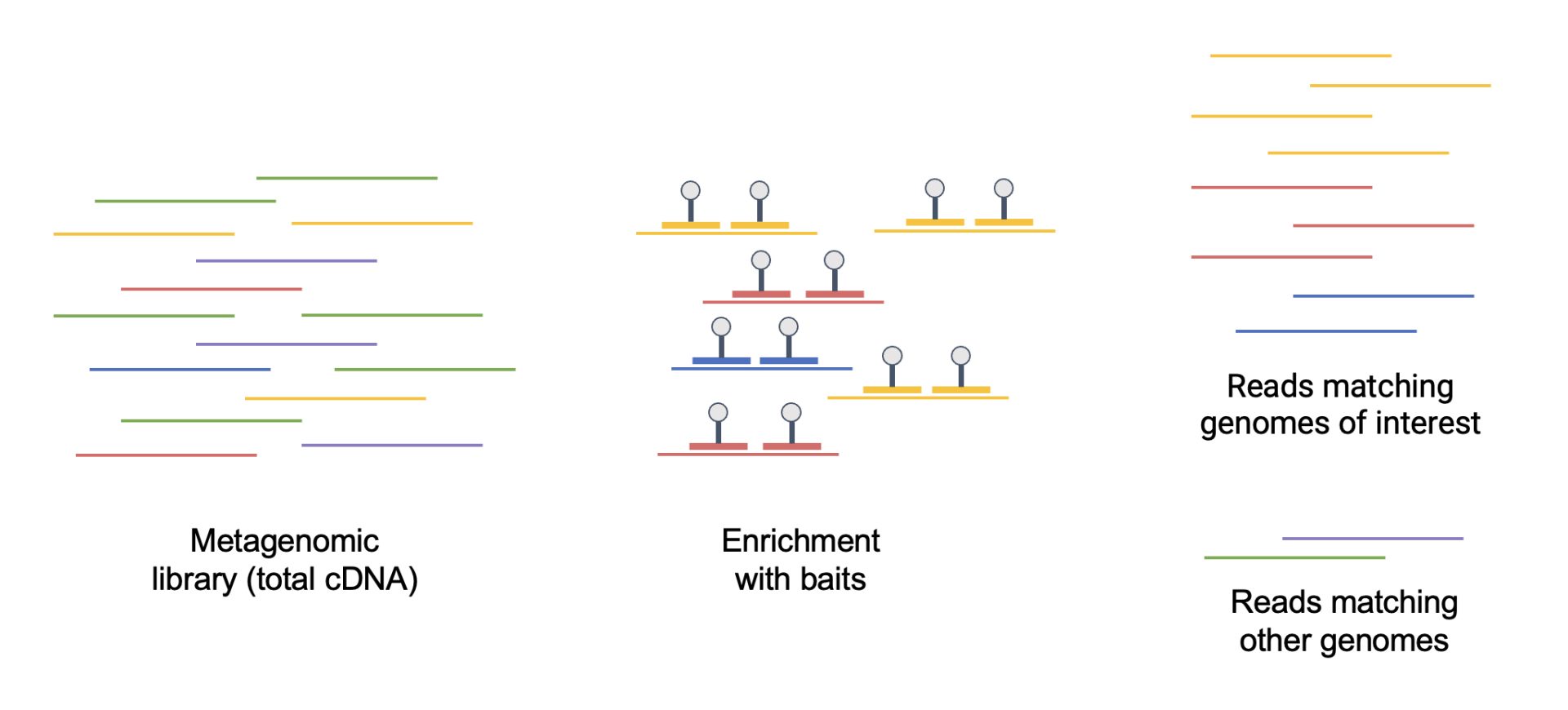

At the Sanger Institute, as part of our efforts to understand SARS-CoV-2, we established large-scale workflows to help sequencing. Now, researchers involved in the Respiratory Virus and Microbiome Initiative have expanded on this to sequence all clinically important respiratory viruses. The team has been harnessing bait capture, a targeted method that uses synthetic DNA probes (baits) to enrich specific genomic regions. More specifically, the team is using baits that target 29 species and variants of mostly respiratory viruses – including the flu. This approach allows individuals to sequence closely related viruses, for example, if we had this technology at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic we would have been able to sequence SARS-CoV-2 with SARS-CoV-1 baits.

Bait capture technique to enrich targeted DNA sequences. Image credit: Diego Teixeira / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

The team is using bait capture as part of a collaborative project with the UKHSA. This work involves sequencing samples from the UKHSA-led SIREN – SARS-CoV-2 Immunity and Reinfection – study. The SIREN study was established early during the COVID-19 pandemic to understand immunity following SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination amongst healthcare workers. The study involved regular nasal/throat swabbing as well as the collection of blood samples and questionnaire data. Now, the UKHSA SIREN team have established a collaboration with the Respiratory Virus and Microbiome Initiative team at Sanger to expand our understanding of the impact of different respiratory viruses circulating amongst healthcare workers in the UK.

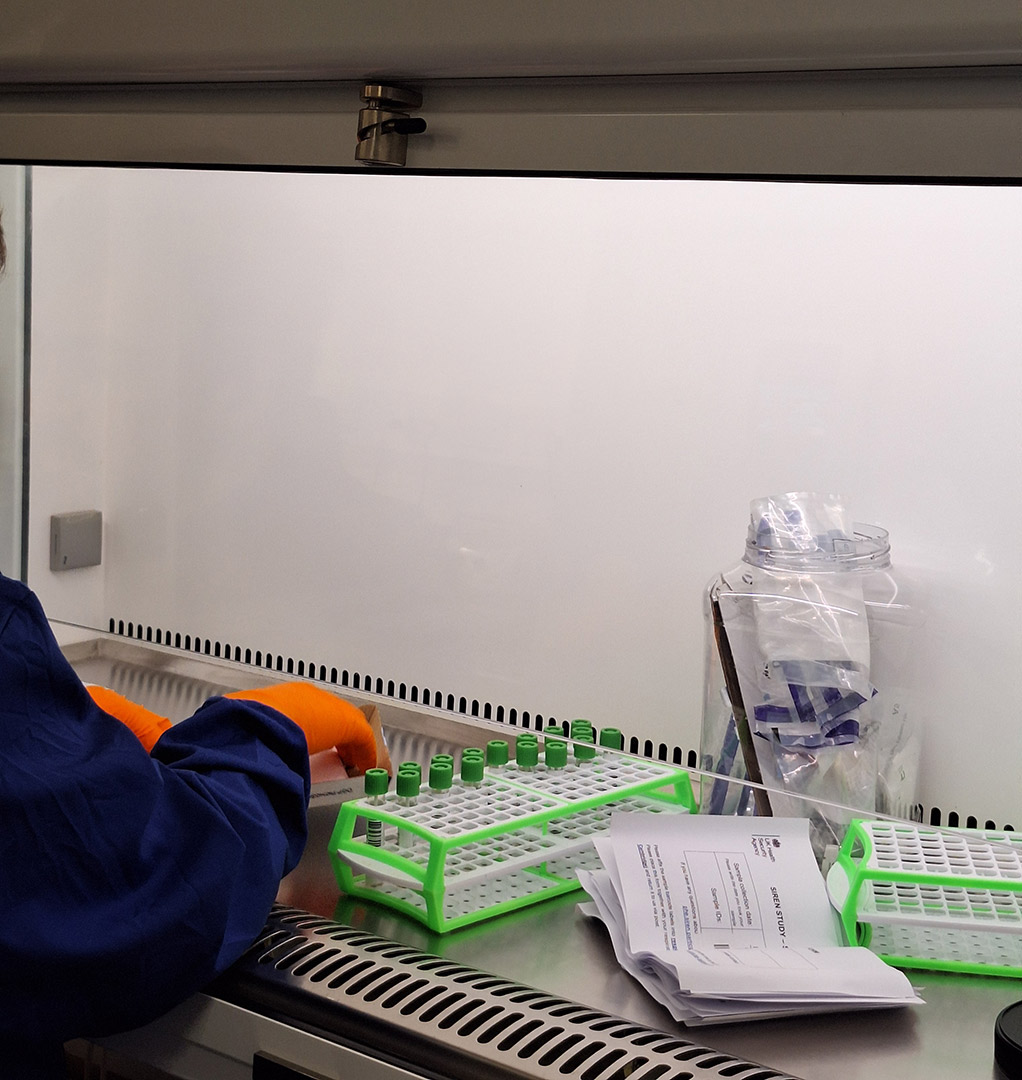

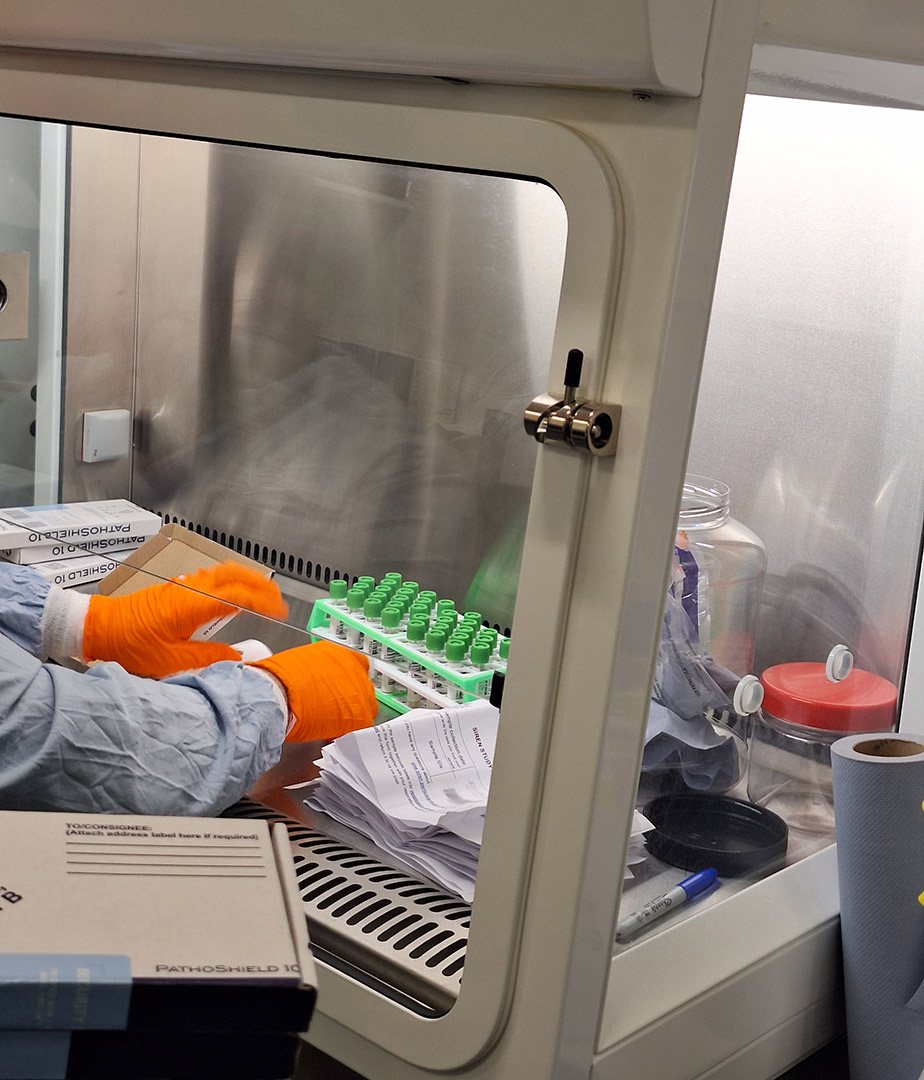

Processing SIREN samples for DNA sequencing and analysis to understand people's nasal microbiomes. Image credit: Katie Bellis / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

At the Sanger Institute, we have received around 60,000 nasal/throat swabs from anonymised SIREN participants from winter 2023 to 2024, combined with fortnightly symptom reports. These data have been used to try and understand what might be driving respiratory illness in this population over time and linking this to symptoms. This year, as part of a new SIREN sub-study called SIREN+ Prepare, led by UKHSA, we have started to receive samples for eight weeks during winter 2025/26 as well as symptom reports from 750 healthcare workers. This will allow researchers to follow what is happening on a weekly basis in terms of the dynamics of respiratory illness in healthcare workers over the winter. This dataset will likely include influenza samples belonging to subclade K, which once sequenced, could help explain its unusually early spread this season.

“Healthcare workers were disproportionately affected during the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the nature of their work. However, this group remains at increased risk each winter from circulating respiratory viruses that include flu, SARS-CoV-2 and respiratory syncytial virus, as they remain highly exposed in healthcare settings. This makes healthcare workers an important population to study, and the UKHSA SIREN study is a great opportunity to understand how to tackle winter pressures, detect new variants of flu and prepare for future pandemics.”

Dr Jasmin Islam,

Consultant Infectious Disease & Microbiology, SIREN Study team, UKHSA

Why is understanding all respiratory viruses important?

Most people are familiar with the flu and COVID-19, but there are many other respiratory viruses out there that are understudied and underappreciated in the population. As a result, this new SIREN sub-study will generate large numbers of sequencing data for some of these other viruses. With this, we can provide a better understanding of respiratory viruses, which in turn could inform new interventions, such as vaccines or other infection control measures that can help tackle winter pressures.

Another avenue this work will unlock, will be unravelling which viruses tend to occur together during illness – known as co-infections – and whether demographic factors or viral genetics can predict this. Relatedly, it will help to explore whether having a co-infection affects the amount of either or both viruses present? Another question is whether co-infections are transmitted together. For example, if someone has flu and rhinovirus, do they pass on both or just one? The team hope to explore the mechanisms behind this. Using symptom data, they also hope to determine if co-infections make people sicker compared to being infected with a single virus.

Alongside this, the team will be studying seasonal effects. For example, does getting flu early in the season protect against other viruses later? Does having a cold in December increase the chance of flu in February? With samples from the same people over time, the team can analyse which viruses are likely – or unlikely – to occur together.

Moving forward, the team hopes to secure additional funding to collect and sequence samples in real time next winter. This would hopefully improve our understanding of circulating viruses and help build more accurate models to predict future trends. This would also be an excellent case study for the feasibility of metagenomics in a surveillance function for respiratory viruses going forward. Having both real-time and retrospective data will also allow the team to identify patterns and trace the origins of virus importations.

“Flu and other respiratory viruses can pose serious risks, sometimes leading to severe illness or death. At the Institute, our work alongside our amazing collaborators, such as the UKHSA SIREN team, aims to understand how these viruses affect healthy adults. This knowledge will help guide the implementation of effective interventions in the future. In many cases, testing is never done to determine which virus causes respiratory illness in adults, so our study will provide new insights into virus biology and interactions – knowledge that is increasingly important in a world continually affected by respiratory infections.”

Dr Marissa Knoll,

Postdoctoral Fellow, Parasites and Microbes research programme, Wellcome Sanger Institute

References

- NHS England. NHS facing ‘worst case scenario’ December amid ‘super flu’ surge. December 2025 [Last accessed: December 2025].

- Kirsebom FC, et al. Early influenza virus characterisation and vaccine effectiveness in England in autumn 2025, a period dominated by influenza A (H3N2) subclade K. Eurosurveillance. 2025; 30: 2500854. DOI: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2025.30.46.2500854

- Hay J, et al. Evaluation of the epidemiological outlook of the influenza A/H3N2 clade K in England during the 2025-26 season. Zenodo; 2025. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.17704678