Image credit: Cell images from NIH BioArt.

Ever wondered what your cells are up to in their own neighbourhoods? Spatial transcriptomics is opening a new frontier where space meets gene expression, revealing hidden insights into how tissues function, interact and change in health and disease.

Think of the series of children’s puzzle books, Where’s Wally? Or Where’s Waldo? in the US. Wally is an instantly recognisable character in his red-and-white-striped top, bobble hat and glasses. The aim of these books is to find Wally and his friends hidden in intricate, bustling scenes filled with amusing characters and details.

Not only are these books enjoyable for children and adults alike, but they can also provide a helpful analogy for understanding spatial transcriptomics – a cutting-edge technique revolutionising biology and shaping the research we do at the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Imagine walking into a shop and buying a Where’s Wally? book, shredding all the pages and mixing them together like confetti – super realistic, right? This is a bit like doing bulk RNA-sequencing. For years, bulk RNA-seq was the standard approach for understanding gene expression. It is a method to analyse the gene expression levels of a population of cells, rather than individual cells. In other words, you can still tell what colours are present in the pile – like measuring the total abundance of different RNA molecules – but you do not yet know which characters – the cells – those colours came from or where they are located on the page. It is a simple, cost-effective and high-throughput approach, but it offers low resolution and lacks spatial context.

Now, flip to the back of the book, where you are introduced to the characters – Wally, Wilma, Wizard Whitebeard and more. This is akin to single cell sequencing. You now know who is in the book and what they look like – much like how single cell sequencing identifies each individual cell and its distinct features.

Single cell sequencing is a technique to analyse the genetic material – DNA or RNA – of individual cells rather than a large population of cells. It allows you to define cellular diversity, or heterogeneity, and identify rare cell populations, providing you with increased resolution but reduced throughput compared to bulk RNA-seq. However, just like bulk RNA-seq, you lose the spatial information – you still do not know where your characters appear in the scene.

Now comes the fun part: opening the pages and searching for Wally and his friends in their crowded scenes. This is like spatial transcriptomics. You now not only know who the characters are – the cells – but you can also find out where they are in each scene – representing different areas of a tissue, such as skin or gut.

Spatial transcriptomics is a technique that maps gene expression within the context of a tissue, uncovering how different genes are expressed in specific locations. This approach reveals how different cells are arranged, how they interact and what roles they play in specific locations.

In the books, finding Wally can be tricky. Similarly, spatial transcriptomics comes with its own technical challenges – from resolution limitations to data complexity. But with time, refinement and technological innovation, our tools are getting better and better – and one day, our spatial images may even rival the illustrations of Where’s Wally? illustrator, Martin Handford, himself.

In this blog, we explore how spatial biology is changing how we see and do biology, and what challenges must be addressed in order to maximise the benefits of this revolutionary genomics approach.

Space is everything to make progress

“Location, location, location!” exclaims Professor Muzz Haniffa, Head of the Cellular Genomics Programme at the Sanger Institute. No, Muzz is not naming her favourite reality property programme – but is emphasising why spatial is important.

In many disease studies, blood is often used as the primary sample because it is easy to collect and reflects changes happening throughout the body. The blood acts as a conduit – ferrying immune cells, signalling molecules and other biomarkers – and offers a convenient window into systemic biology. However, blood is not where most diseases, such as inflammatory conditions or solid tumours, actually originate or develop. The key events are occurring in specific tissues and cellular neighbourhoods. This is where spatial genomics becomes transformative, allowing us to study gene expression and cellular interactions directly at the site of disease, within their tissue context.

For any multicellular organism, space is everything. The majority of cells in the body have the same genome, which has all the instructions for life. When we get sick, it is because an organ gets sick and that is because there is something failing, usually, in the way cells work in the organ. These organs are not a bag of random cells, they are very spatially organised and this organisation is vital for their function. They have their particular place in the tissue with a particular neighborhood of cells that help them to do the right thing. They are in constant communication, which is all coordinated in a carefully orchestrated way across the body.

To make progress in understanding and treating disease, spatial context is important. Up until 20 years ago, experiments to analyse human tissue and understand cell biology were mostly done by studying cells cultivated in dishes and looking at one cell type and how it adapted to live in a dish. This is very far from what the cells in our body are actually doing in vivo. While this approach taught us what happens within cells, it did not provide us with insight into what happens in organs, and how cells actually live and do what they are supposed to do within the context of all other cell types that exist.

To find efficient treatments for disease, we need to understand how the organs work, how all these cells interplay in a healthy way, and what happens when that interplay goes awry and does not work as it should. Using spatial technology, we can begin to work on this level of complexity which can enable us to understand the fundamentals of human biology.

A joint view of biology

The necessary breakthrough for the development of spatial technologies was single cell genomics because it was the first time we could provide a full view of all the genes that are active within the different cell types.

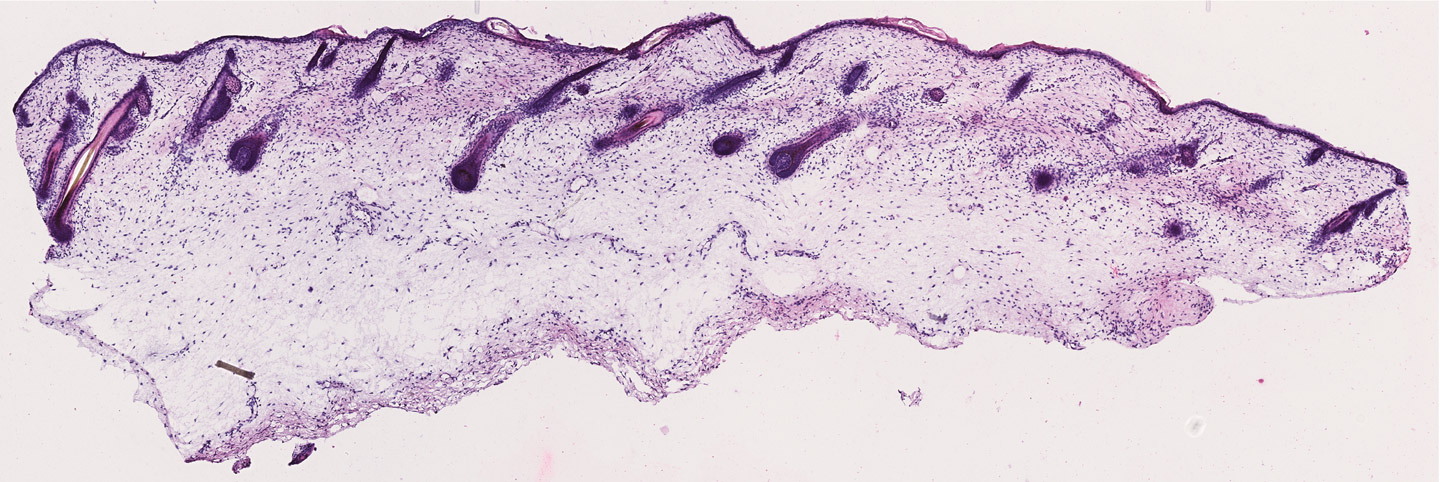

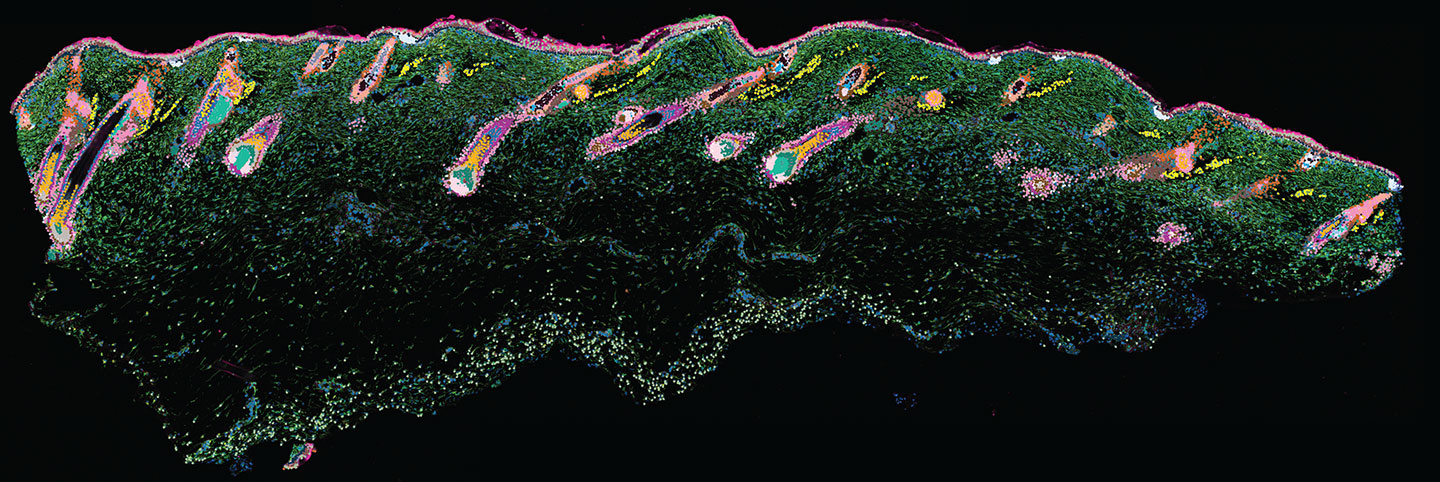

This allowed experts to start building spatial transcriptomic methods as they had a reference of the RNA environment in tissues as a starting point. The next step was then associating the RNA information from each individual cell with their positions in the tissue. While there are different technologies available, in general, spatial transcriptomics involves slicing a tissue finely, treating it with a chemical to allow the RNA material inside the cells to leak out onto a slide and bind to barcoded spots, sequencing the barcoded RNA and then combining it with imaging data.

While we now have information about space, we can also link all of this to the knowledge we have of tissues. This comes from historical histological studies. It involves using old techniques to section and stain tissue, and then observing the tissue under a microscope.

We can link this old histological and pathology knowledge with more recent spatial omics knowledge, providing us with a coherent, joint view of biology that has not been seen before. This will have a huge impact on biology and drug development going forwards.

“We are in that phase where sequencing was when next generation sequencing came out 20 years ago. Sequencing was once expensive and then it became more affordable and now it is in clinical practice. The first draft of the human genome was published over 25 years ago and was only fully completed in 2022. There is always a delay with these things. I believe a similar thing will happen with spatial – we will get better with time. I think the industry will be a key driver in this and scientists will work in parallel to develop new concepts that could be adopted by one of those platforms in the future.”

Professor Mats Nilsson,

Associate Faculty at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and Platform Director at Science for Life Laboratory

The integration of spatial transcriptomics platforms into our research at the Sanger Institute is transforming the questions we ask and the insights we ultimately gather. From unpicking the complexity of glioblastoma – aggressive brain tumour – to unravelling what goes wrong in skin diseases, our scientists are harnessing these new tools to provide a whole new layer of biological understanding. As spatial transcriptomic technologies become more refined and higher throughput, they will continue to change how we study health and disease, enabling more discovery and driving precision medicine forward.

Further developments to maximise use

The last ten years has seen tremendous development in spatial technologies. There are now machines that can do spatial biology at high throughput, producing robust and high-quality data. However, these technologies are still very expensive and can be quite slow depending on the number of genes you are looking at.

Another challenge of spatial transcriptomics is that some of the early platforms captured gene expression from clusters of cells rather than single cells. This can be challenging with human tissues where lots of cells are packed together or when applied to less complex organisms, such as worms, where completely different cell types can be very close together. There are newer methods attempting to improve this resolution, but they can be technically demanding.

Other challenges surrounding spatial are related to changes in how scientists work. For example, precise tissue preparation is important to ensure that the tissue and therefore the data produced are of high quality. Some spatial platforms also only work on certain types of samples, like fresh-frozen tissue. In addition to these upstream elements, researchers also have to develop new tools to support downstream data analyses, including data visualisation and interpretation. Enabling the integration of spatial data with other modalities, including proteomics and metabolomics, will be a critical development to maximise insights even further.