Image credit: Wellcome Sanger Institute

Fatigue. Pain. Brain fog. Organ damage. Repeat. These are just some of the symptoms experienced by people living with lupus. Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease that causes inflammation all over the body. It predominantly affects the skin, joints and internal organs such as the kidney and heart.

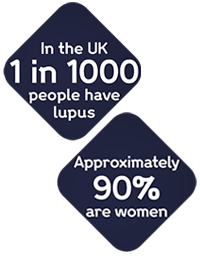

Approximately five million people worldwide have lupus, primarily impacting those assigned female at birth and people from Black African, Caribbean and Asian ancestries.1,2

People with lupus experience delays in diagnosis and management, which can increase burden of disease and organ damage. While treatments are available, access to these treatments, particularly more advanced therapies, as well as diagnostic tests are limited in low- and middle-income countries.

In recognition of UK Lupus Awareness Month, we caught up with Catherine Sutherland, Computational Senior Staff Scientist in the Human Genetics programme at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, to discuss more about how their work is contributing to our understanding of lupus.

1. What is lupus and why is studying it so important?

People with lupus can experience unpredictable disease flares that can be triggered by many things, including stress or infections, which can severely impact their day-to-day lives. There is no cure for lupus and many of the current treatment options have side effects that can make them difficult to tolerate. Therefore, understanding more about this condition and how it arises is important to develop more targeted treatment options and help to improve patient quality of life.

2. What are some of the challenges surrounding lupus research and treatment?

Lupus is a very heterogenous condition – the symptoms experienced, and the underlying disease processes can vary considerably between patients. This complexity makes research challenging as findings are not always consistent between different people. Response to treatment is also highly variable and a drug that helps one person may not help another. This makes developing new drugs hard as it is difficult to know in advance who will benefit from a specific treatment.

The prevalence of lupus also differs a lot across people of different ancestries, with it being least common in individuals of European ancestry. However, historically, much of genomic research has been carried out in European populations, meaning the results are not representative of the people who are most affected by lupus. For example, in the UK, a study found that the incidence of lupus was highest in Black Caribbean individuals.4

Ancestry also affects disease severity and outcomes. For example, in a US study, African American women were found to have the highest rates of lupus nephritis – a kidney complication caused by lupus.5 In addition, NHS figures recently showed that Black patients in England are much more likely to be hospitalised because of lupus than White patients.3

3. How are we contributing to lupus research at the Sanger Institute?

In Dr Emma Davenport’s group, we use functional genomics to understand immune responses in health and disease. This is an area of research that explores how the genome functions through gene expression and regulation and can help to explain the heterogeneity in response to many conditions. We are currently applying these methods to several ongoing lupus projects.

We recently conducted a small single-cell study where we analysed data from nine lupus patients before and after they received a monoclonal antibody drug called rituximab. By following the immune system over time in these patients, we were able to identify changes that occurred in response to the drug and how these differed in individuals who responded well to the treatment compared to those who did not. In the future, work like this will hopefully help us to predict in advance which treatments will be effective for everyone.

Catherine (front row, fourth from the left) and her colleagues in the Davenport research group. Image credit: Wellcome Sanger Institute.

We have also been analysing single-cell expression data and whole genome sequencing data from around 300 lupus patients of African or Afro-Caribbean, European and South Asian ancestries. This diverse multi-ancestry cohort is really exciting because we can look for any differences in genetic regulation across patients with differing disease severities, clinical features and ancestry backgrounds. The main aim of this work is to understand regulation of gene expression in individual cell types in order to identify potential new drug targets. Much of this work has been led by Haerin Jang, a PhD student in our group.

I have also been coordinating bulk gene expression and genome sequencing data generation for an even larger lupus study where we have samples from around 750 lupus patients and 150 healthy people. This project has also recruited from across multiple ancestries, including from Indigenous Australians, and will help us further understand the molecular processes that influence ancestry-specific differences in lupus.

Catherine at her desk in the Sanger Institute's Human Genetics programme. Image credit: Haerin Jang / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

4. What role do emerging technologies play in advancing lupus research?

One of the genomics techniques we are using for our lupus work is to map expression quantitative trait loci or eQTL. This involves identifying regions of the genome that are correlated with the level of expression of a gene, in other words, finding changes in the letters that make up our DNA that affect how much a gene is turned on or off. Finding eQTLs can help us understand how previously identified genetic signals may contribute to disease as well as potentially point to new genes of interest.

By using single-cell techniques, we can perform these analyses at much higher resolution than was previously possible. For example, we can look for effects that may only occur in a single cell type – something which would often not be detectable in bulk data. Single-cell data also gives us a much more detailed picture of the immune system and can allow us to identify rare cell populations that may contribute to disease.

5. Where do you see lupus research heading in the future? What do we need to get there?

I think that because lupus is such a variable disease and treatment cannot be a ‘one size fits all’ approach, there will be a continuing focus on personalised medicine. To allow this to happen, we need to be able to combine clinical and omics data, which includes different sets of biological information such as genomics and proteomics, so that we can stratify patients more easily. This will help clinicians to choose the appropriate treatments for them and even predict disease flares before they happen.

To enable truly personalised medicine, more targeted therapies with fewer side effects will need to be developed. These are likely to include new biological therapies, types of treatment which are based on the mechanisms that our own immune systems use. Recently, there have been promising immunotherapy trials using CAR-T cells – genetically modified patient immune cells – and two new monoclonal antibodies that have been approved for treatment. These should hopefully provide new options for patients.

It is also important that research continues to include people from all populations affected by lupus so that those who have been under-served in the past can now benefit from new advances.

References

- Pfizer. Lupus [Last accessed: September 2025].

- Lupus UK. What is lupus? [Last accessed: September 2025].

- The Guardian. Black people in England eight times more likely to be hospitalised with lupus. February 2025 [Last accessed: September 2025].

- Rees F, et al. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the UK, 1999–2012. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 2016; 75: 136–141. DOI: 1136/annrheumdis-2014-206334.

- Feldman CH, et al. Epidemiology and sociodemographics of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis among US adults with Medicaid coverage, 2000–2004. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2013; 65: 753–763. DOI: 1002/art.37795.