Image credit: Petra Korlević / Wellcome Sanger Institute

Kids often have the best questions, and mosquitoes — the world’s deadliest animal — hold so many secrets. Inspired by real questions from 7-year-olds, we dive into some fascinating facts and learn what genomics can reveal about one of nature’s tiniest troublemakers.

Listen to this blog story:

Listen to "How many mosquitoes are there in the world? And other buzzing questions" on Spreaker.

At a recent 'Skype a Scientist' session, a year 2 class from Hawley Primary School in Camden had so many great mosquito mysteries for Wellcome Sanger Institute staff scientist, Petra Korlević, that she brought them back to our specialists in the Genomic Surveillance Unit (GSU) and Tree of Life programme to solve. To mark World Mosquito Day, here are four surprising ways that genomics can answer deceptively difficult questions from 7-year-olds. So grab your curiosity — and maybe some bug spray — and let’s get started.

1. Is this a mosquito? [*Holds squished bug up to the camera*]

It is hard to tell just by looking at a smear what kind of insect this is. The legs, wings, head, and other body parts lost their definition when it got squished. It is the number and shape of those features that help you tell a mosquito from a wasp or a fly. Bug experts — also called entomologists — can even use small differences in these physical features to find out what kind of mosquito this was. The exact type of mosquito matters, because they can carry different diseases.

Malaria parasites need mosquitoes in the Anopheles group to spread, while Yellow Fever and Dengue are transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. If it wasn’t squished, you could use the three Ps — position, palps, and pattern — to help determine what kind of mosquito you caught. But even a squished mosquito still contains enough DNA to tell us a lot about not just what kind of mosquito it is, but if it has any special powers, like resistance to mosquito-killing chemicals called insecticides.

In fact, ongoing research by a team in the Sanger Institute’s Tree of Life programme hints that slightly squishing a mosquito might actually be better for preserving its DNA.

Dr Fiona Teltscher, Staff Scientist in the DNA pipelines Research and Development team, explains that the standard way to ship mosquito samples is on dry ice, with a preservation solution like alcohol or a chemical called ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid — also known as EDTA. This approach has limitations though. “Normally, shipping something on dry ice is incredibly expensive,” she says. “And sometimes it’s just not possible at all.” This could be because there isn’t access to dry ice where the mosquito was collected, because the dry ice would evaporate in the time it would take to ship, or because it is classed as a dangerous good and requires specialist couriers.

The team wondered if, by cracking the exoskeleton of the mosquito, they could help the preservation solution better penetrate the tissues. Using a tiny pestle, they gently squished the mosquito against the side of the test tube. What they found was that the DNA of mosquitoes who had experienced this rough treatment lasted longer than those that had not been squished.

So, while squishing may make it hard to tell by eye what mosquito you are dealing with, if you do it gently, it can actually help preserve the DNA.

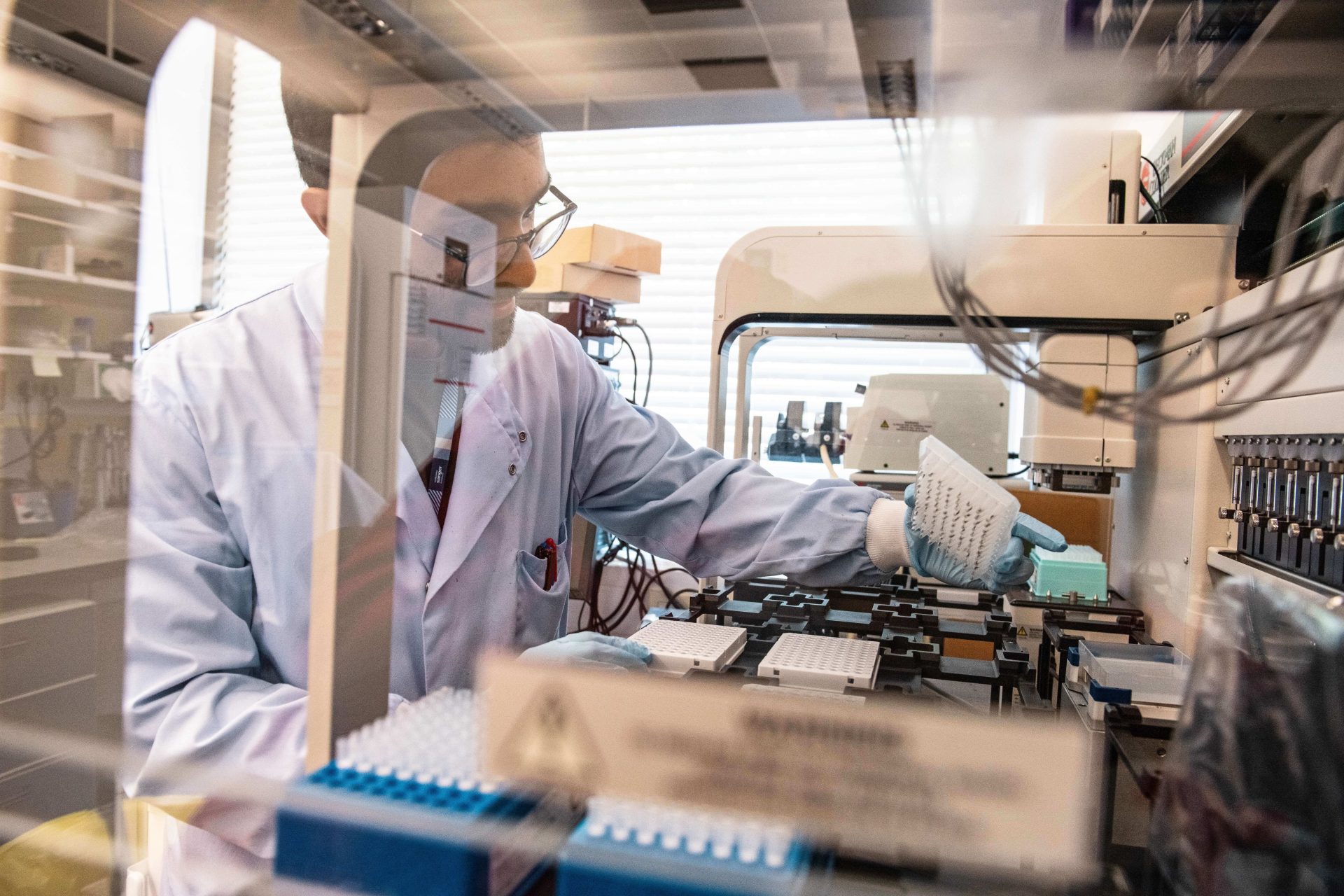

Researcher inspecting mosquito samples in a 96-well plate before extracting DNA for sequencing (left) and close up of a 96-well plate with mosquitoes. Credit: Greg Moss / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

2. Are there any evil mosquitoes in the UK?

If by “evil,” you mean carry diseases, then the short answer to this question is no.

For the longer answer, we spoke with Dr Kelly Bennett, Senior Data Scientist in Sanger’s GSU, who works to track disease-carrying mosquitoes. While her current work with MalariaGEN is focused on malaria-carrying Anopheles mosquitoes in Africa, she has also studied Aedes mosquitoes and their ability to invade new environments.

“Currently, mosquitoes in the UK are only considered a nuisance because they bite humans but do not transmit disease. However, we do have species of mosquitoes in the UK that have the ability to transmit diseases to people, such as Culex mosquitoes, which are vectors of West Nile Virus. We haven't had any reports of locally acquired cases yet, but West Nile Virus is on the rise in Europe, and it could be a problem in future.”

Patterns of mosquito-borne disease can change as the environment and land use changes. For example, malaria used to be endemic in the UK,1 explains Kelly: “In the 19th century, Anopheles mosquitoes present in the UK transmitted malaria to people in marshy coastal areas before land changes and improved sanitation led to the disappearance of reported cases.”

There are still several species of Anopheles mosquito present throughout the UK,2 but they do not carry malaria because there are very few humans infected with the parasite from whom the mosquitoes can acquire it — only the occasional traveller returning from countries where malaria is present.

Of more concern in the near future is Aedes albopictus, also known as the tiger mosquito. Kelly notes: “The tiger mosquito is a vector for insect-borne viruses, such as dengue, chikungunya and Zika. It has made its way into northern Europe as far as France and has been responsible for disease outbreaks of chikungunya in Italy.” There is also currently a large outbreak of chikungunya spreading in China, likely because of this mosquito.

So, while there are currently no — or very few — “evil” mosquitoes in the UK, there were in the past and there may again be in the future. By integrating genomic information about the mosquitoes with environmental and demographic information, the GSU aims to give a better picture of the risk of mosquito-borne illnesses both in the UK and around the world.

3. How many mosquitoes are there in the world?

“That’s a great question, and one that many entomologists would like to know the answer to. The short answer is that no one really knows,” says Dr Jon Brenas, Senior Data Scientist in the GSU’s Vector team. Jon works on MalariaGEN and the Malaria Vector Genome Observatory, which is funded by the Gates Foundation.

Jon admits that the longer answer is a guess, but it reveals why genomics is an important tool for studying mosquito populations.

There are more than 3,700 known mosquito species. But some, like Anopheles gambiae, which is a major vector for malaria, are not just one species. They exist in what is known as a species complex, with several populations that have distinct features but can still interbreed. There are eight recognised members of the Anopheles gambiae species complex, but recent research using MalariaGEN data resources curated by the GSU has identified two further ‘cryptic’ forms called Pwani and Bissau that are also impossible to distinguish by eye but are genetically different.

To make the job of estimating population a little bit easier, Jon suggested the following: “If we limit the question to the number of mosquitoes in the wider Anopheles gambiae complex in Africa, the most recent estimates using genomic data find an effective population — a measure of the size of the gene pool — of around 66,000,000 individuals.3 That’s around the population of the UK.”

He continues, “If you include seasonal variations, the census population — the number of individual mosquitoes — can probably reach one billion. That’s more than the number of people in Europe.” So, if you assumed that each mosquito species has about that same population and multiplied that number by a thousand, you would get one trillion.

But Jon is quick to point out, “This is barely an educated guess.”

Anopheles coluzzi mosquitoes in the Insectary at Sanger. Credit: Rachael Smith / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

4. Are there any pink mosquitoes?

As far as we can tell, there are no pink mosquitoes. But there is a species of mosquito whose iridescent scales make it shine a beautiful blue, green, and purple when the light hits it just right. It also has fuzzy hairs on two of its legs that look like boots. A 2021 picture of it made the BBC ask if it was the “world’s most beautiful mosquito?”

The mosquito in question is Sabethes cyaneus, which is native to South and Central America. And, like over 2,000 other species from around the world, a team in our Tree of Life programme has sequenced its DNA to create a reference genome.

We spoke with Dr Alex Makunin, Computational Staff Scientist in the Sanger Institute’s Tree of Life programme, who is focused on studying mosquito genomes to understand more about the process for sequencing Sabethes.

“The samples were sent to Sanger by our partners in the US who have maintained a colony of this species since 1988,” says Alex. Next, the samples were passed through a series of laboratory and computer-based processes in the Sanger Institute to extract, sequence, and assemble the DNA into a genome. It was completed and released in September 2022.

Sanger’s Tree of Life programme aims to sequence all animals, plants, fungi and protists. These genomes unlock new information about life on Earth, and by having the blueprint of an organism – its DNA – experts can study its evolution, support conservation efforts, or search for new biomedicines.

Drawing of a Sabethes cyaneus mosquito. Credit: Petra Korlević / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

References

- Walker M D. The last British malaria outbreak. British Journal of General Practice 2024; 70 (693): 182–183. DOI: 10.3399/bjgp20X709073.

- UK Health Security Agency. Mosquitoes species profiles. Gov.uk; March 2025 [Last accessed: August 2025].

- Khatri B, Burt A. Robust Estimation of Recent Effective Population Size from Number of Independent Origins in Soft Sweeps. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2019; 36(9): 2040-2052. DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msz081.