Image credit: Wellcome Sanger Institute

We caught up with experts from the Cellular Services team at the Wellcome Sanger Institute to learn more about what organoids are and how we are using them in our research.

Listen to this blog article:

Listen to "5 questions on organoids with Hongorzul Davaapil and Amy Yeung" on Spreaker.

Over the last decade, organoid research has rapidly evolved, creating a pivotal shift across stem cell biology, developmental biology, regenerative medicine and biotechnology. These ‘mini organs’ in a dish are three-dimensional (3D), self-organising structures that mimic features of real organs, and are powerful models for studying human development, disease and therapies.

In this blog, we caught up with Dr Hongorzul Davaapil, Technical Specialist and Dr Amy Yeung, Head of Cell Services, both of whom work in Cellular Services within Scientific Operations at the Sanger Institute. They share insights into growing organoids, their opportunities and limitations, and how the Institute is using them to advance our understanding of health and disease.

Hongorzul Davaapil

Hongorzul: My name is Hongorzul Davaapil, and I am a Technical Specialist in the Cellular Services team. I work on organoid models, setting up projects and getting all the information from internal faculty. I also train our research assistants and advanced research assistants on how to do the process. I add lots of quality checking steps and make sure that the process is reproducible, regardless of which individual is actually doing it.

Amy Yeung

Amy: My name is Amy Yeung, and I am the Head of Cellular Services within Scientific Operations. My team supports research through cell modelling – including organoids and stem cells – as well as screening and genetic manipulation, such as creating cell lines modified to track gene expression or protein activity. Unlike faculty labs that focus on discovery research, our core facility specialises in scaling up experiments and developing robust, reproducible processes.

1. What are organoids? What is the process of growing an organoid model?

Hongorzul: Organoids are cell-based, miniature 3D structures. You can think of them as little mini organs. They have specific properties where they are capable of self-renewal and self-organisation. In order for them to grow, you don’t have to do anything special because they have an innate ‘stem cellness’, which allows them to keep growing and propagating.

They have similar features, functionality and structures to real organs, which is what they are based off. A lot of the native cell shape and morphology are maintained because they are in a 3D configuration and have cell-to-cell contact and a microenvironment, which is very conducive to the native state. This is different to artificial 2D cultures, where they are flattened on plastic and on a much more rigid structure. With organoids, cells are in a softer tissue-like environment.

Another thing that is very important for the functionality of an organoid is that cell polarity is maintained. So, a lot of organoid models are epithelial based, meaning you have a basal side, which points towards your media and the outside, as well as an apical side, which points inwards. This apical-basal polarity is really important for epithelial function.

Depending on how they were generated, the cellular diversity you have within an organ, and therefore an organoid, is also retained. Let’s say you have a gut organoid, and in that gut organoid, you might have a variety of specialised cell types present which provide you with some functionality for what the gut would actually, for example, mucus production. These can be generated from stem cells – either from primary biopsies such as foetal, paediatric or adult stem cells, or they can be differentiated directly from pluripotent stem cells such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These are stem cells that are derived from adult somatic cells but have been genetically reprogrammed to an embryonic stem cell-like state.

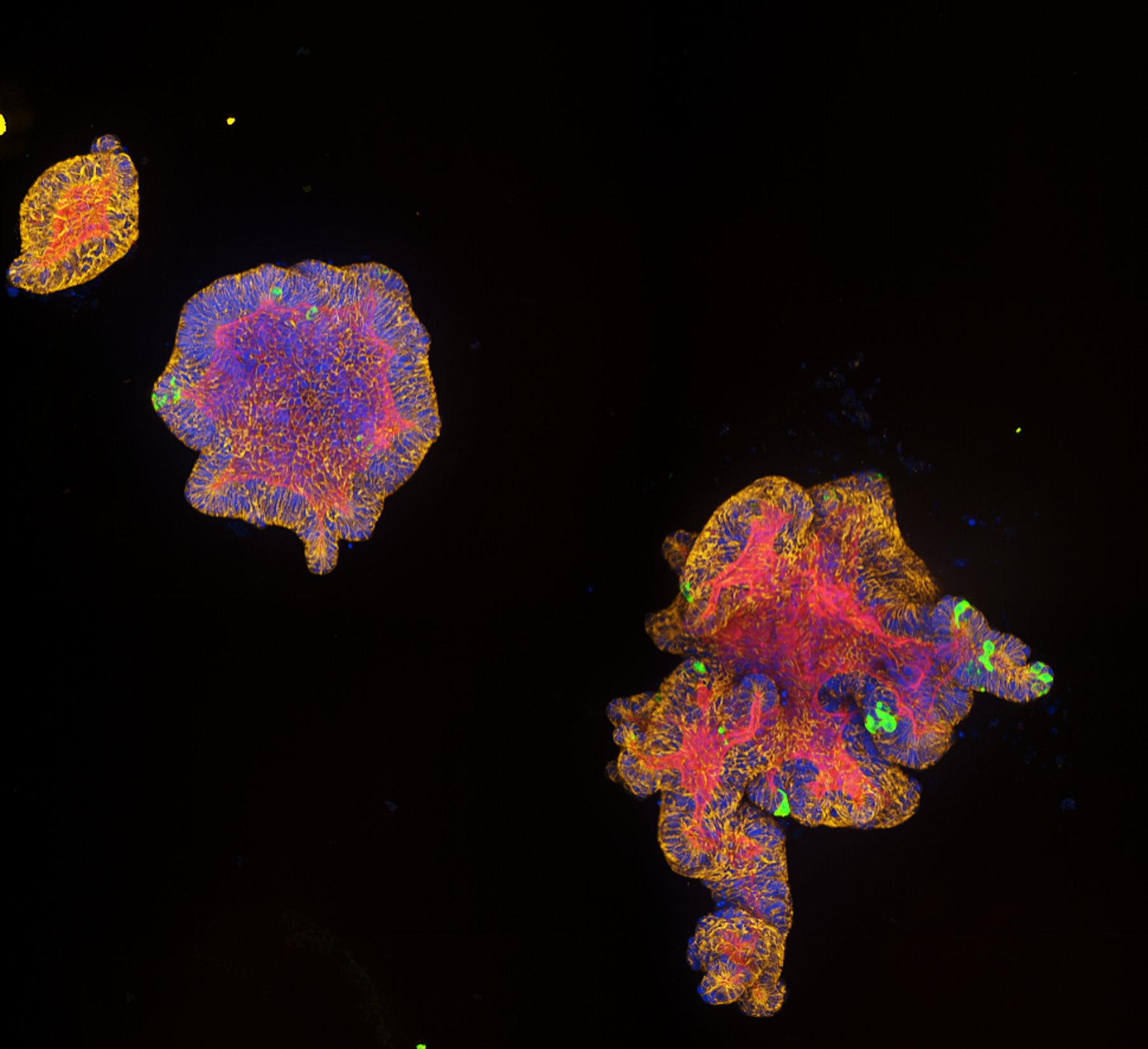

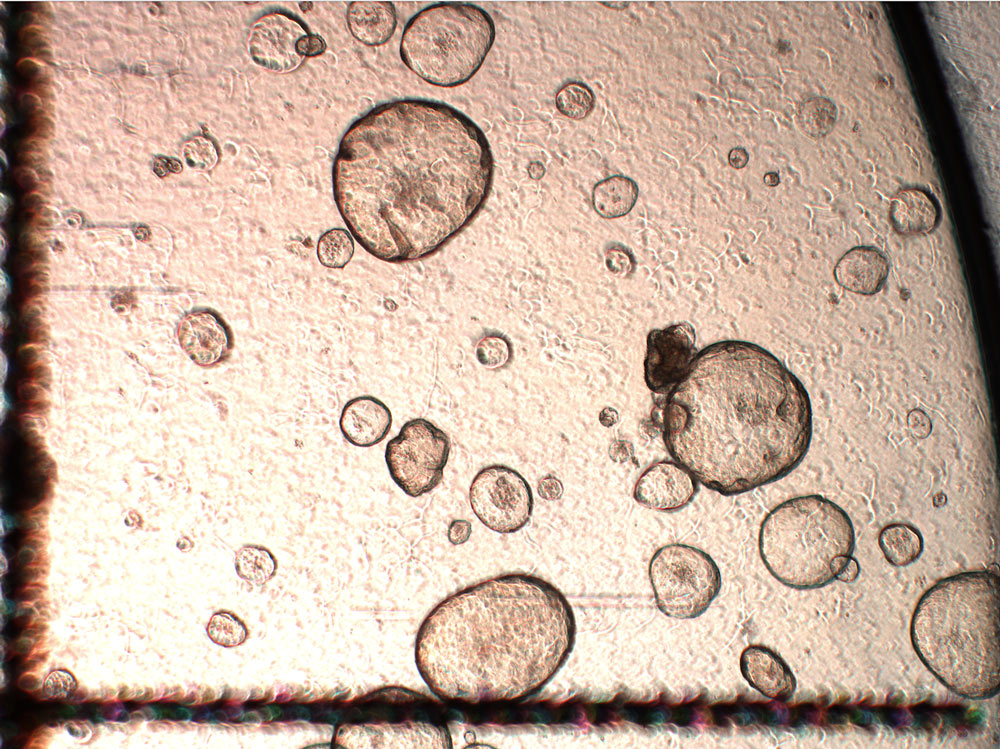

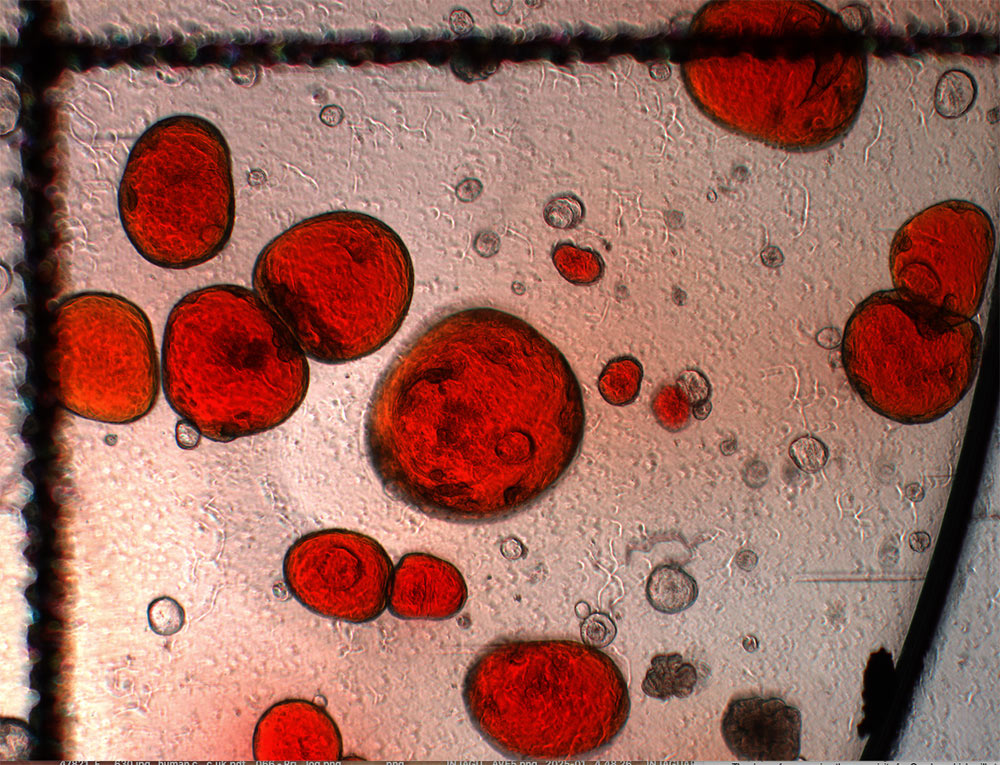

Intestinal organoids from healthy donors. Credit: Maryna Panamarova / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Organoids are typically grown in a scaffold. There are basement membrane extracts such as Matrigel, which we use for a lot of our projects. This extracellular matrix provides the right conditions for the organoids to form in the first place, but it also gives them the correct properties to be able to grow. This includes tensile properties, stiffness, rigidity, growth factors, matrix proteins like collagens, laminins and fibronectins – all of which would really mimic the tissue that they would normally be embedded in.

Their size very much depends on the type of organoid and where they come from. The definition of an organoid can be quite vague. For example, we have ‘gut organoids’ in the lab that are iPSC based and they are relatively small. But then we have others that are from primary sources, like foetal gut organoids, that are comparatively much larger. If we let them grow for a long time, they could possibly reach a couple of millimetres.

Amy: For us, skin organoids are probably one of the largest types of organoids we have worked with; you can easily see them with the naked eye. These are iPSC derived, so we work closely with Professor Muzz Haniffa’s team in Cellular Genomics who are working on the skin and skin diseases. They use skin organoids to model disease variants. And these are grown to the millimetres in semi suspension, and you can see them forming hair follicles. It is really fascinating.

Skin organoids. Credit: Maryna Panamarova / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Hongorzul: In order to continue growing organoids, you have to undergo a process called passage. Passage is when you take your organoid, you break it up into smaller chunks or single cells, you put these chunks or cells into fresh Matrigel and media, and then you give them space to grow even more. In terms of how long you can grow an organoid for, it again depends on the application. You may only want to keep an organoid at a low passage because, just like cells cultured in 2D, the more passages you accumulate, especially with primary cells, the more you move away from that native tissue. Passage is a much more artificial process than just maintaining them by giving them fresh media. For example, for a biobanking project, you keep organoids in culture for a total of maybe two or three weeks, depending on how quickly they grow, because you want to bank as much as you can as early as possible. But we have other projects where the organoids are very slow growing by nature, so you need to keep them for longer. Typically, our rule of thumb is more to do with passage number, rather than necessarily length of culture, because if an organoid takes a long time to grow, and another organoid model is much faster at growing, they would have accumulated more passages in that same time frame.

There are particular projects where our objective is to generate a repository, a resource for faculty that would allow them to have access to a variety of organoid models that have been generated in a very specific way for downstream applications. This is where we take primary tissue, create organoids from those by isolating the epithelial cells that are going to make up the organoid, put them to Matrigel, allow them to grow, and then bank as much as we can with the fewest passages as possible. This allows us to create a very reliable source of the same organoids.

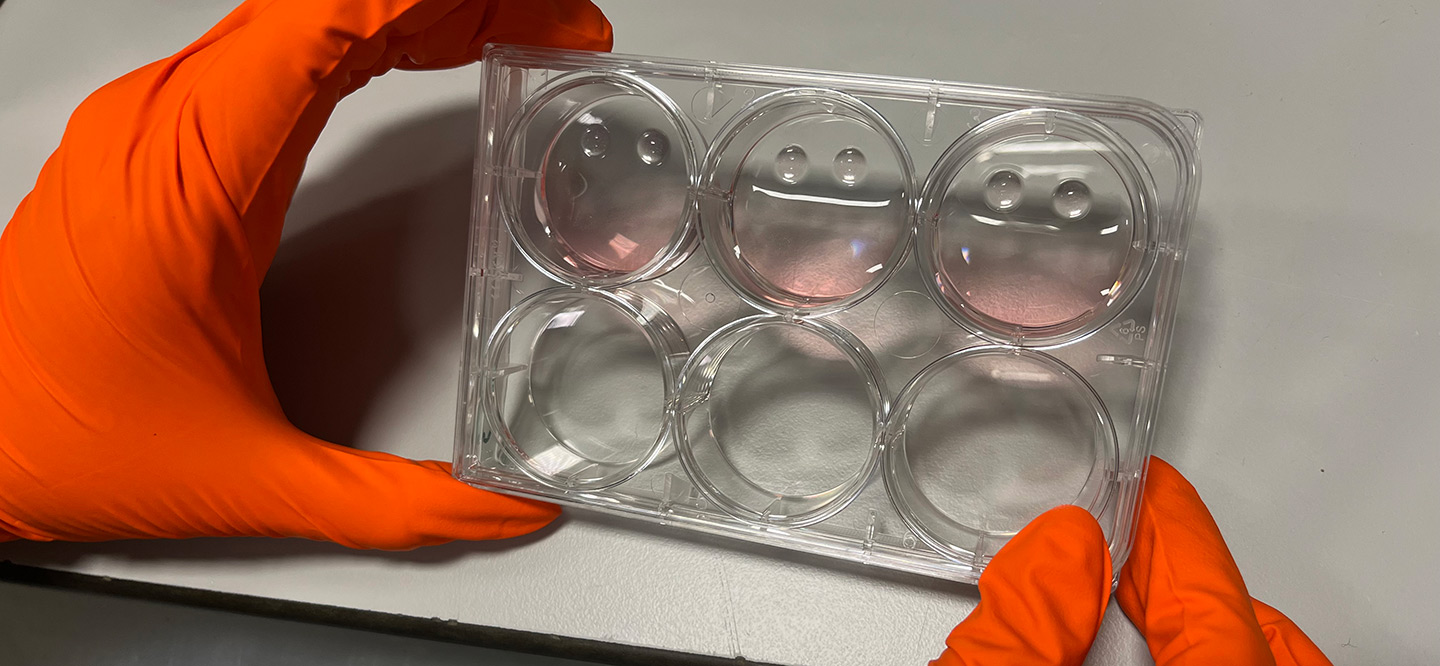

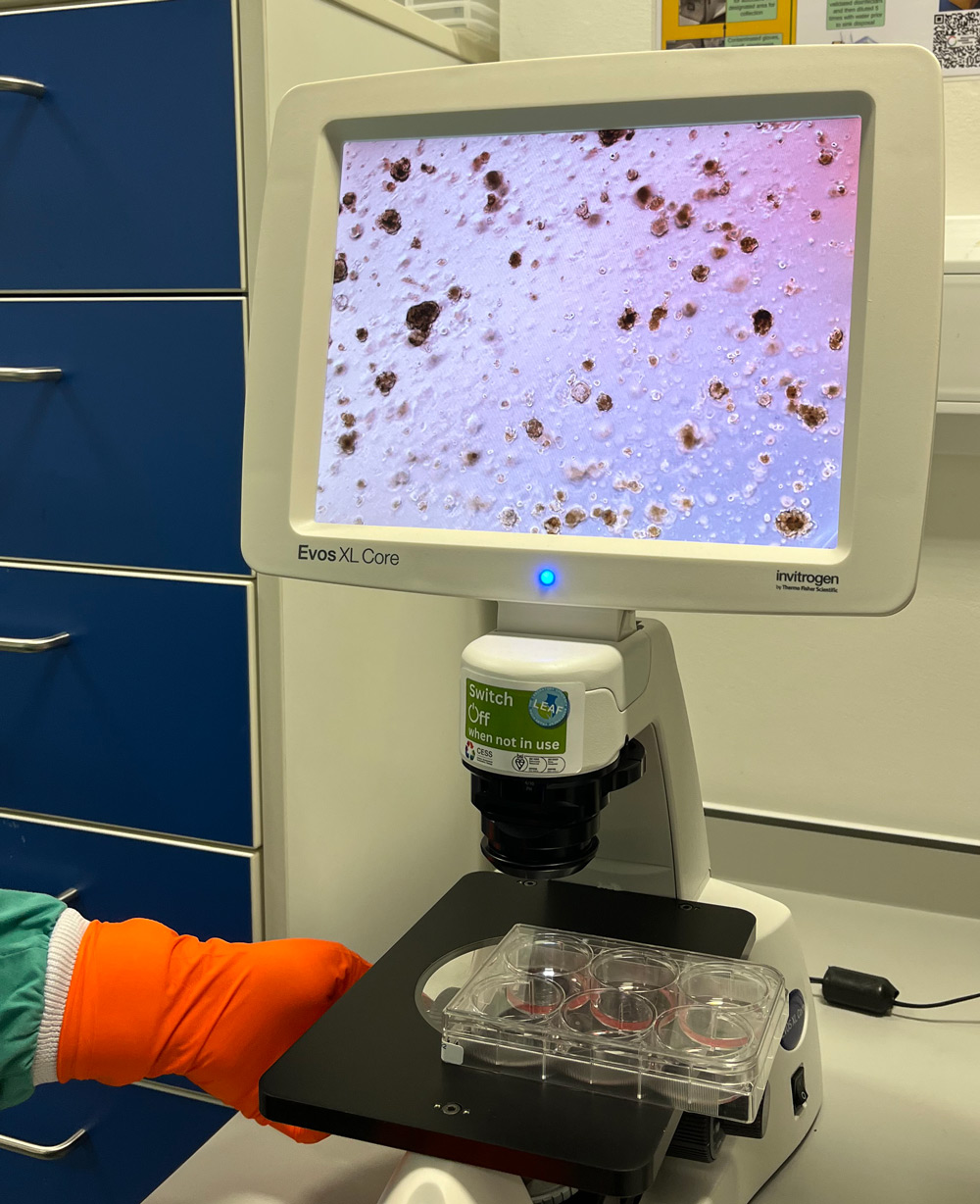

Media used for growing organoids (left), placental organoids in a dish on Matrigel with fresh media (middle) and placental organoids under a microscope (right). Credit: Shannon Gunn / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

If a scientist is interested in an organoid line from the bank we have generated, we can connect them with the relevant faculty owner at Sanger. They can then thaw the cryopreserved vial in their own lab and use it for their experiments. If they have surplus material, they are also able to bank some for future use. Ideally, each cryovial supports more than just a single experiment. Some organoid lines are particularly difficult to grow and therefore quite valuable, so we try to maintain and expand those lines as carefully as possible.

There are cases that we have seen with some of our projects, where if you keep an organoid line growing for a long period of time, they start to just slow down after accumulating a number of passages. They start to behave differently, and they start to have a bit of a different morphology. You probably would not want to use these for your experiments. The timeframe for this can be a bit different for each organoid type and line. So, we try to recommend faculty that they use the organoids at the lowest possible passage that they can get away with.

Amy: It also depends on the source of the organoid. For instance, cancer-derived organoids are particularly prone to accumulating mutations over time in culture. One way we address this is through genetic analysis. For example, Dr Mathew Garnett’s team sequences both the original tissue and the derived organoid lines we generate to compare their genomic profiles. They examine whether any genetic changes have occurred during the initial passages required for organoid establishment and banking.

2. What are the opportunities of using organoids for research?

Hongorzul: A lot of what we know about biology comes from animal models, particularly mice. These are extremely valuable and still have their place in research. However, they are costly because you have to pay for animal housing and welfare, along with considering the ethical concerns involved in using animals for research. As a result, they are not very amenable to scaling up. The other problem is that they are physiologically different to humans, especially smaller species, for example, a mouse would metabolise drugs way faster than a human. When you try to bring in larger, more comparable animals to humans, like pigs, they are incredibly costly. It is more likely that they would be used for smaller-scale experiments, rather than anything that would require a significant number of animals.

The other extreme is using 2D human cells, which are very high throughput but simplistic. They are flat cells, grown in plastic and artificial conditions. They lack any mechanical and microenvironmental cues. So again, they are not really a good proxy for modelling human organs, especially when interrogating complex mechanisms.

Organoids fall nicely in the middle of that spectrum where you have human cells, and they have mechanisms and gene expression profiles that are going to be conserved between human cells and human tissues. They are relatively simple to manage, you don't require the same level of facilities you would for animal models. But you can also fine tune the complexity, so you can have a relatively simple organoid model, or you can also have an organoid model where you include co-cultures of different types of cells, so you can start to build up layers of what is physiological. You have this flexibility that you don't necessarily have with simple 2D cultures or animal models.

I think the biggest opportunity for organoids really is in the scalability. The fact that you can investigate huge numbers of samples for mechanistic studies or drug screening is a big plus.

Amy: Another opportunity for organoids is moving towards personalised medicine. For example, if you know someone has a genetic disease, you can use organoids to look at how they would respond to certain therapies because every individual is different. This would give us an understanding of how a patient would respond and allow us to develop treatments that are better tailored to the patient. I think this is an area that science is moving towards.

3. What are the current limitations of organoids?

Hongorzul: It is a relatively new field compared to the wealth of experience people have with cell lines and animal models. I think one of the big things, especially when you want to go into standardised testing, is the fact that you have to use basement membrane extracts like Matrigel. A lot of the organoid systems are very reliant on this extract, and these are actually derived from mouse tumours. This contains a variety of undefined factors, which will vary pretty significantly between batches, and can influence how organoids grow. So, if you have the same model, grown in two very different batches of Matrigel, you might have two quite different outcomes.

The way in which our team try to circumvent this limitation, especially for projects where you have to maintain a very consistent quality of pipeline, we try to order lot-specific batches of Matrigel that have the same composition. This is a workaround that we have at the moment, but it is still something that the field in general needs to work on in order to have something that is chemically defined and therefore, allows for more reproducibility between experiments and also collaborators.

Another important consideration is size, which is limited by how well nutrients and growth factors can diffuse through the organoid. You can think of it a bit like a tumour – when it is small, nutrients can easily reach the centre, but as it grows, the inner cells may start to die due to lack of access. This same limitation applies to organoids as most currently reach only a few millimetres in diameter. Scaling them up beyond that, into the centimetre range, requires introducing vasculature or some kind of perfusion system to deliver nutrients throughout the structure. Achieving that level of complexity is a major technical challenge. But researchers are exploring ways to grow more complex, vascularised organoids, so that could hopefully change in the future.

The other limitation is difficulty in generating disease-specific organoids, for example, organoids derived from primary tissues. If you have a biopsy that is in great condition from a healthy donor that does not have any kind of disease on it, it will form organoids generally pretty well. This is because the cells are all in good condition and it is less likely that they would have any underlying pathology that would prevent them from forming organoids. However, for some of our projects, if you have a biopsy from an individual with severe disease, it is much more challenging to generate organoids from those individuals compared to healthy donors.

Amy: Unlike in current organoids, our cells in the body are surrounded by other cell types such as immune and neuronal cells. I think increasing the complexity and getting a better representation of disease is the direction people want to get to in the future. Because organoids might respond differently if fibroblasts, which contribute to connective tissue formation, or immune cells are added. Cell-to-cell interactions have a huge effect on how cells respond to drugs and genetic perturbations.

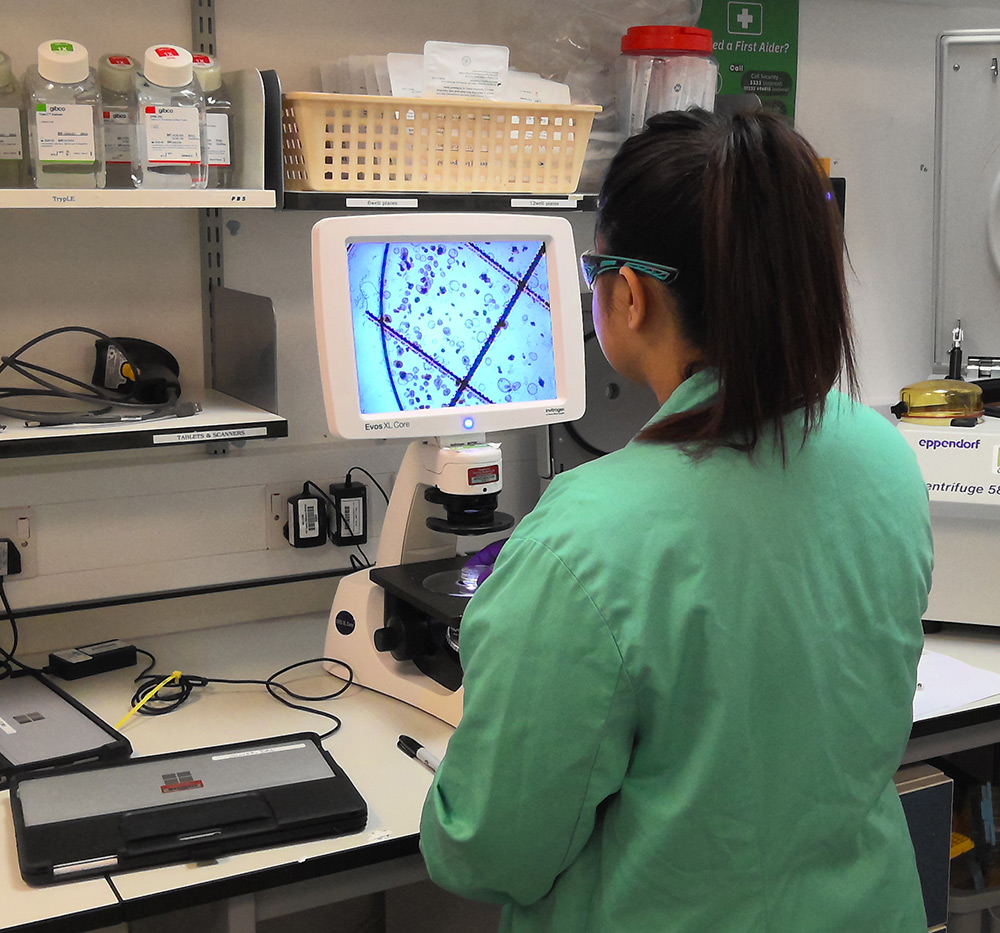

Shayeri Das (left images) and Cameron Collins (right) working on organoids. Credit: Hongorzul Davaapil / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

There is always a trade-off between how biologically representative a model is and how feasible it is to scale up and cost-effectively implement. Technologies like organ-on-a-chip are exciting breakthroughs that many in the field are exploring. These systems use engineered or naturally derived miniature tissues housed within microfluidic devices that precisely control fluid flow – often to mimic blood vessels or other physiological conditions. While these approaches are innovative, they are currently expensive, technically challenging and difficult to scale. Running something like a genome-wide CRISPR screen on these platforms is not currently practical. So, as scientists, it is important to understand the limitations of each model system.

Growing organoids, especially those derived from stem cells, can be quite costly, often requiring expensive growth factors and specialised media, unlike standard 2D cell cultures.

Hongorzul: Another challenge to add to that, as I mentioned briefly earlier, is how we define an organoid. For example, we have two different projects in our team where we work with gut organoids, and I think the cost of the media, even though we refer to them both as ‘gut organoids’, is astronomically different. One of the media is about four or five times the cost of the other. This is because different stem cell sources require specific media composition, as well as the different aims for each project. It will be important for researchers who work on the same broad type of organoid to get together to try and understand the terminology and the minimum requirements needed to grow these models.

Amy: One of the strengths of our facility is the breadth of experience we have built over the years by working across all the research programmes at Sanger. We have cultured organoids derived from a wide range of tissues including cancer, colon, ovary, gut, and foetal, which means we have accumulated a comprehensive set of protocols and associated data. That is incredibly valuable. For example, if a researcher is interested in generating a gut organoid enriched for mucus-producing cells, they can refer to the existing protocols we have developed to assess whether they meet their needs. Having this depth of data on diverse organoid types is a powerful resource for the broader research community.

4. How are we using organoids in our research at Sanger?

Amy: Project Gro was a seven-year project that was in collaboration with Mathew Garnett’s team. It was part of the Human Cancer Model Initiative, an international effort to generate, characterise and annotate the next generation of cancer cell models as a resource for the scientific community. Project Gro aimed to derive and bank hundreds of organoid models that came from various human cancer tissues like colon, lung, ovaries and breast. These were all banked and quality checked, and then sent back to faculty as well as the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) – a well-known tissue bank that distributes cell lines and organoids to the scientific community across the globe. This ensures that everyone around the world can benefit from the organoids that are banked from the Sanger Institute.

Endometrial organoids for the ReproOrgs project. Credit: Hongorzul Davaapil / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Hongorzul: We also have a collaboration with Roser Vento-Tormo’s team for two projects. One of the projects is biobanking for endometriosis organoids – called ReproOrgs. Endometriosis is a disease that affects ten percent of women worldwide, but we still have a very poor understanding of how it begins and how to treat it. For this project, we are getting biopsies from a variety of individuals, including those with and without endometriosis, developing organoid models and then banking them at the earliest possible point to hand them over to internal faculty.

In this project, we are also able to isolate, at the same time as organoids, 2D fibroblasts, which are also integral for the biology of the endometrium. So, from one biopsy you end up with two different cell lines. Dr Charlotte Cassie , one of the postdocs in Roser’s group, is very interested in doing a variety of co-culture experiments with organoids and fibroblasts, as well as macrophages and immune cells, which will gradually increase the complexity of the model. Through RNA sequencing, they will hopefully be able to show interesting features about the intricacies of the menstrual cycle and clues as to what might be going wrong in endometriosis.

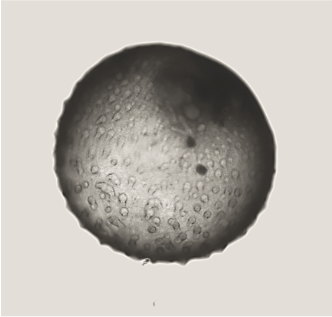

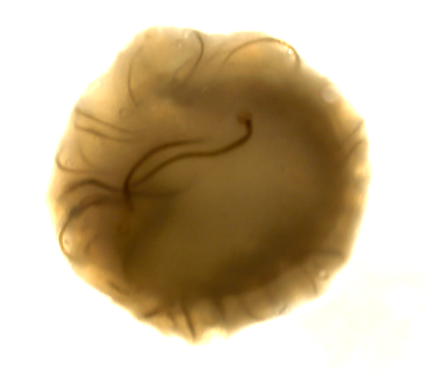

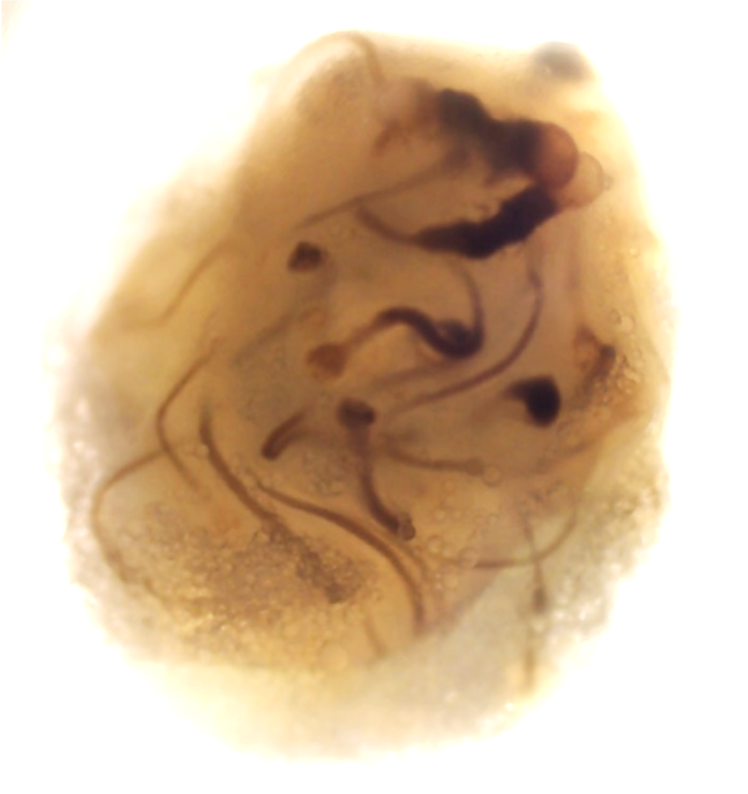

The second project that we have been involved in is about placental organoids called TrophoSphere. The placenta is the first organ that forms during pregnancy, and it is foetal derived rather than maternal derived. It has a really big impact on how the pregnancy proceeds, whether there is a miscarriage, whether everything goes smoothly, or whether the woman develops complications such as preeclampsia. One of the main determinants is how deeply this organ embeds itself within the maternal endometrium. If it is too shallow, you might have problems where the foetus attempts to divert too many resources from the mother, and this can be difficult to manage in the case of pre-eclampsia. If it is too deep, it can also be problematic, for example, in the case of placenta accreta where there is risk of major haemorrhage following delivery.

For this project, led by Postdoctoral Fellow Dr Ana Paredes in Roser’s team, we have these immortalised trophoblast stem cells, which are specialised cells that can differentiate into various placental cell types. Using these we can create two types of organoids: ones that are non-invasive – they grow in their own little space, and don’t migrate – and ones that are highly invasive. They start off round, and then they eventually start creating these tendrils that would seek out the maternal endometrium to be able to attach and adhere. They are very different phenotypes, and they are very striking in how they look.

Placental organoids for TrophoSphere project – day 0 to day 16. Credit: Hongorzul Davaapil / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

The bORGs Project is another piece of work being led by PhD student, Madelyn Moy, where we have organoids from the gut that we want to microinject with different compounds. As I mentioned earlier, organoids have a very specific polarity. The outside part is what faces your blood vessels and other things, and the inside part is actually the lumen of whatever you are modelling. If you were to apply compounds to just the outside, you would not really be recapitulating a very physiological event. In the bORGs Project, we have developed a methodology to physically inject every single organoid with various compounds. In Madelyn’s project, she is very interested in looking at short chain fatty acids, which are products of digestion in the microbiome. In order to understand the role of the microbiome during early-life, Madelyn is interested in figuring out the impact of these microbially-derived short chain fatty acids, specifically on the lumen side of the organoids. Organoids are at most one millimetre in diameter, so they are quite small. So, you have to use a very specific microinjection setup to be able, with a microscope, inject in these short chain fatty acids. It is quite a laborious process, but one that gives you, in my opinion, probably much more physiological data, as opposed to just adding the short chain fatty acids in the media, and then hoping that somehow some of it will end up in the lumen of the organoid.

Uninjected gut organoids (left) and injected organoids (right) for bORGs Project. Credit: Hongorzul Davaapil / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Microinjection of gut organoids for bORGs Project. Credit: Hongorzul Davaapil / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

5. What do you see as the future of organoids in research?

Hongorzul: I think something that the whole field has to come to terms with is trying to find this balance between organ fidelity and model complexity as there is such a fine balance as to what your aim is. Because if it is too simple, it is not physiological and if it is too complex, it is too inhibitory and technically difficult to do. I think the trend that we are seeing at the moment is an easier entry into more complicated systems, like organ-on-a-chip models. I think the fact that we also have access to such a variety of biopsies means that we can understand a lot more of human diversity, especially differences in ethnicities and gender, and how that impacts processes such as drug metabolism. We are heading towards a generation of more complex models that will allow us to interrogate very complex processes, which require a variety of different cell types.

I think it is also important to view organoids as a tool for large-scale outputs, so things like drug screening. For example, they could be used as a first layer in clinical trials. So, rather than using humans to start off your safety testing, you could do some toxicity screening on organoids, and while it will not give you a perfect readout, it will give you a bit more of an idea as to what you would possibly rule out immediately. This would avoid the cost and resource of going through all that screening. Organoids give you some important shortcuts in advancing human health.