Image credit: Mark Thomson / Wellcome Sanger Institute

How do we get diverse samples into Sanger? We chat to the Sample Management team for the Tree of Life programme at Sanger to understand more about how we manage to get samples of eukaryotic organisms for sequencing from all around the world.

Listen to this blog story:

Listen to "Specimens and systems: Streamlining sample management to help investigate life on Earth" on Spreaker.

The Tree of Life programme at the Wellcome Sanger Institute is on a quest to investigate the diversity and origins of life on Earth. The collection and management of samples from different species play a critical part in this. Whether it is a coral from deep in the ocean, or a tiny tardigrade in some of the harshest conditions on earth, these samples carry invaluable genetic, ecological and taxonomic information. These insights could not only support future conservation efforts but could also provide opportunities for new medicines and food security.

But before we get to these insights, we first have to get the samples. The samples we receive here at Sanger come from all over the world, and any one of these is only as good as the system that stores, tracks and preserves it. Effective sample management is critical for ensuring data integrity and future usability of the collected samples.

In this blog, we caught up with Nancy Holroyd, Samples and Partner Relationship Manager, alongside Ian Still and Radka Platte, Sample Managers, from the Sample Management team in the Tree of Life programme to learn about best practice, common challenges, and their drive to streamline processes.

What does the Sample Management team do in the Tree of Life programme?

Nancy: We have developed processes so that we can bring in samples that scientists want for the Tree of Life programme. We ensure that they are brought in with all the appropriate sample metadata, so that when the reference genomes or any other data are produced, all the right details are accompanying them in the public domain. We ensure that we only accept samples that are collected with the relevant permissions, that they've been sampled ethically and that we have the appropriate legal agreements.

In summary, we have developed processes so that the right samples can come in for the science in the right format, in the right timeframe, and with all of the right admin support having been completed.

We have really streamlined things since the programme first started in 2019. To date, we have collected, shipped, or archived over 10,000 species.

What is your average day like as a sample manager?

Ian: One thing that you can guarantee you'll do in every single day is communicating with one or several of the partners that have active samples being submitted to us. The Tree of Life programme has several faculty groups and projects, including the Darwin Tree of Life (DToL), Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics project (ASG), BIOSCAN project, Project Psyche and Biodiversity Genomics Europe. Radka and I split these projects, receiving emails from those partners in our shared inbox and leading on the relationships. On an average day, you would be communicating with these partners, which could be anything from helping with a manifest, talking about and arranging shipping, and helping with any problems once the sample has been shipped.

Ian: One thing that you can guarantee you'll do in every single day is communicating with one or several of the partners that have active samples being submitted to us. The Tree of Life programme has several faculty groups and projects, including the Darwin Tree of Life (DToL), Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics project (ASG), BIOSCAN project, Project Psyche and Biodiversity Genomics Europe. Radka and I split these projects, receiving emails from those partners in our shared inbox and leading on the relationships. On an average day, you would be communicating with these partners, which could be anything from helping with a manifest, talking about and arranging shipping, and helping with any problems once the sample has been shipped.

The manifest is a large spreadsheet that contains over 50 columns of information on the sample. This includes: What's in the tube? What's the species? What part of that organism is in the tube? What type of sample is it? What life stage is it? Where was it collected? How was it collected?

Partners cannot send samples to us until they have filled out the mandatory columns.

Radka: On top of this, you will likely be interacting with some wider teams within Sanger, particularly Legal and Research Governance (LeGo). This team are integral to looking at the metadata for the samples that partners are wanting to submit and doing due diligence to make sure that standards are in line with the law. One key element of their work is making sure we are aligned with The Nagoya Protocol, which is an international framework to ensure the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of genetic resources. Countries may also have their own specific Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) regulations in place which we must also comply with. There are also laws around protected species and protected areas, and we have to ensure the samples we receive are ethically sampled. While we are involved in coordinating the samples that come in, we do rely on the expertise of other teams to ensure we are bringing samples in legally and ethically.

We don't accept any samples until all of that work has been done upfront. We quite often have to manage the expectations of our scientists and partners in regard to these processes as they are sometimes lengthy but fortunately, in most cases, they only take a few weeks. For people sending us samples, if we do all of these checks before receiving the sample, then we have their enthusiasm and attention. We deliberately don’t share our shipping address until everything is approved to avoid surprise samples arriving.

Where do you obtain your samples from?

Nancy: The Darwin Tree of Life, which aims to produce reference genomes for all of the estimated 70,000 eukaryotic species in Britain and Ireland, is our main flagship project. For this, we have collaborated with the Natural History Museum, the Marine Biological Association, the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Wytham Woods at the University of Oxford, the Earlham Institute, the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, EMBL-EBI, the University of Cambridge and the University of Edinburgh. Amongst our partners are experts in sample collection and taxonomy, which is a lengthy process in itself. They provide the largest number of samples to us, and they will go out and collect a wide range of different species. Because they do this a lot, they know what they need to do to process samples in the most efficient way to feed into the Tree of Life pipeline. We also work with other very specialist taxonomists if we need to target certain taxonomic groups.

Nancy: The Darwin Tree of Life, which aims to produce reference genomes for all of the estimated 70,000 eukaryotic species in Britain and Ireland, is our main flagship project. For this, we have collaborated with the Natural History Museum, the Marine Biological Association, the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Wytham Woods at the University of Oxford, the Earlham Institute, the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, EMBL-EBI, the University of Cambridge and the University of Edinburgh. Amongst our partners are experts in sample collection and taxonomy, which is a lengthy process in itself. They provide the largest number of samples to us, and they will go out and collect a wide range of different species. Because they do this a lot, they know what they need to do to process samples in the most efficient way to feed into the Tree of Life pipeline. We also work with other very specialist taxonomists if we need to target certain taxonomic groups.

Ian: We often work with the faculty leads across the programme who know which species are required for the project and where to obtain them. We also have project managers in our programme who help manage the initial relationships with the partners and oversee the projects through to completion.

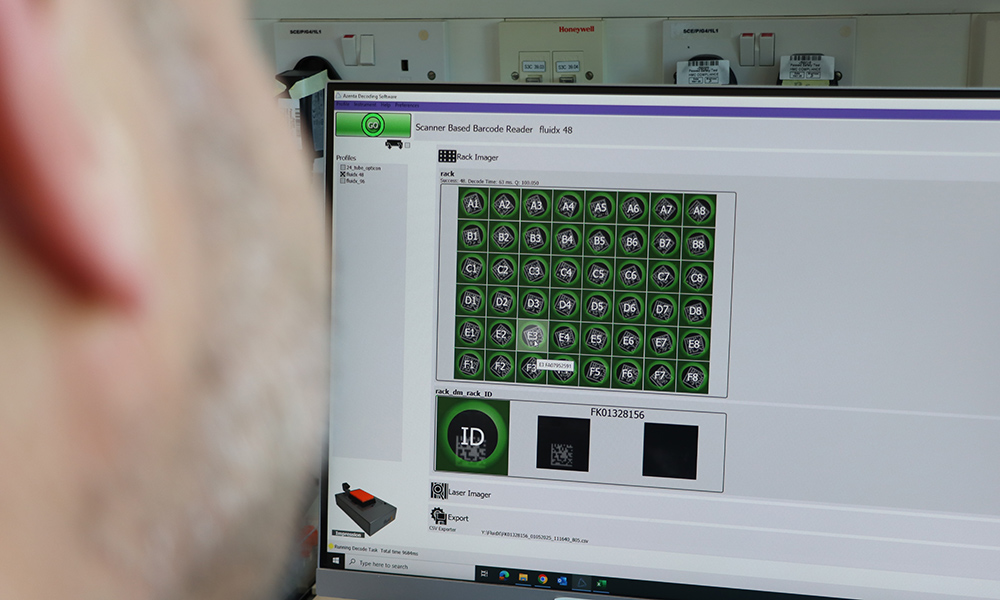

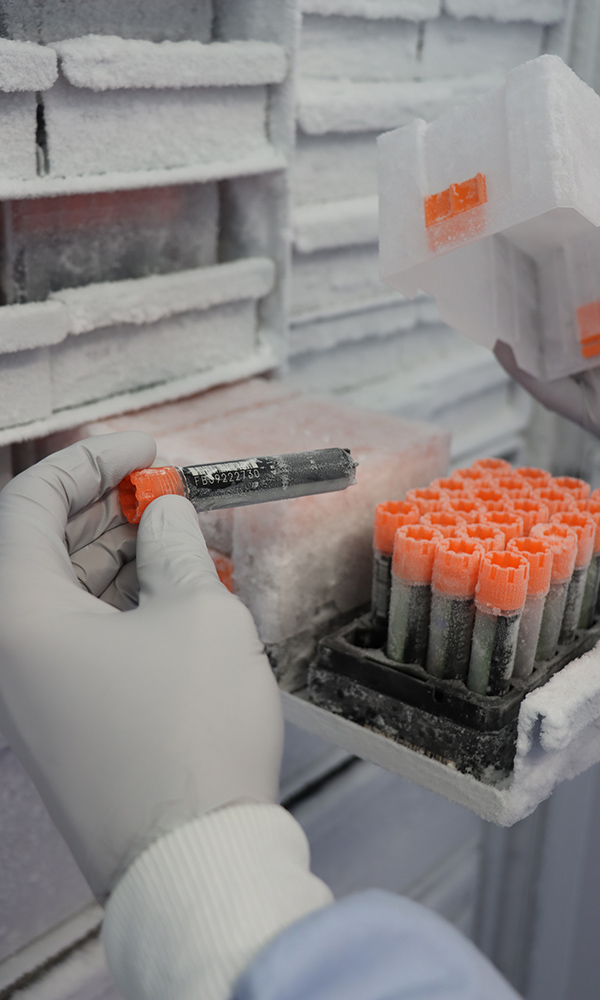

What is the typical life cycle of a sample?

Nancy: I can give you an example. Our collaborators from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh are experts, amongst other things, on bryophytes – a group of plants including mosses, liverworts and hornworts. They would go out into the field and identify the species that we need in real time. The sample would then be DNA barcoded, which involves using a short section of DNA to identify a species. The molecular barcoding data are used to confirm that the sample has been identified as the correct species before it is shipped to us at Sanger. Almost all of our samples come to us in barcoded tubes – not molecular this time, but barcodes like you have in the shops – and we are very strict on this because it enables us to scale up. Different formats of sample tubes make it harder to process in the lab at high throughput.

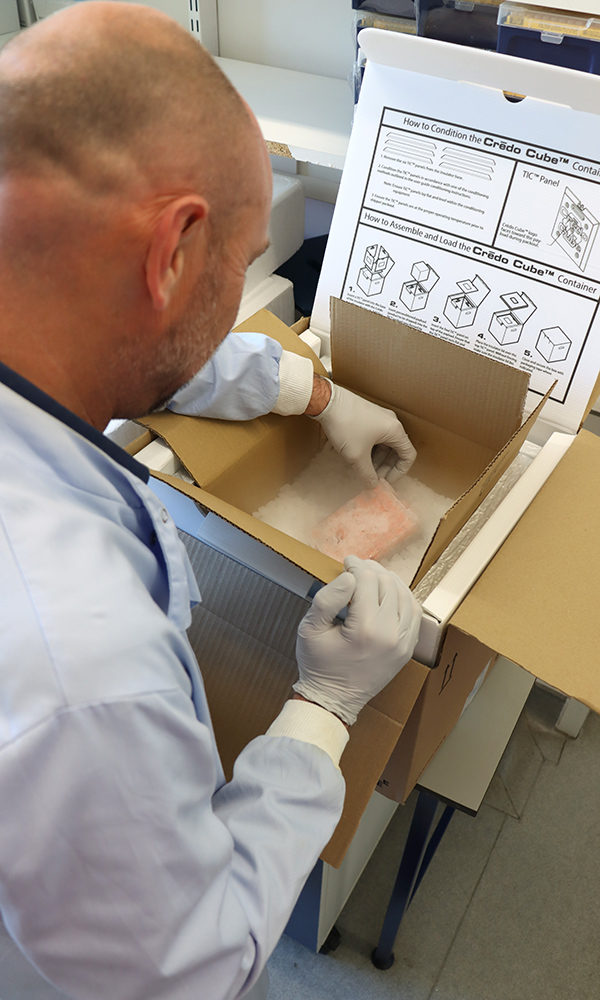

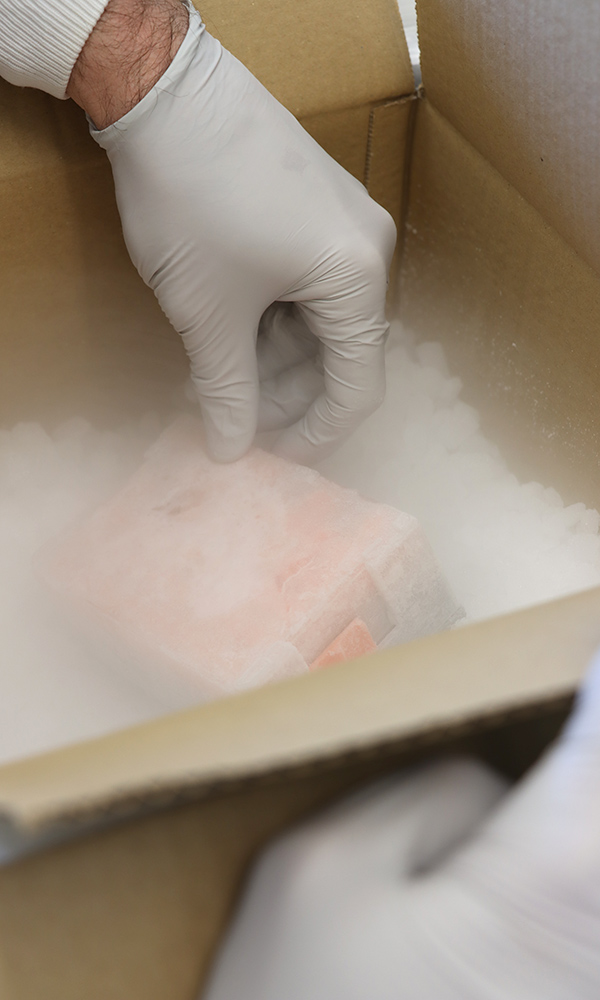

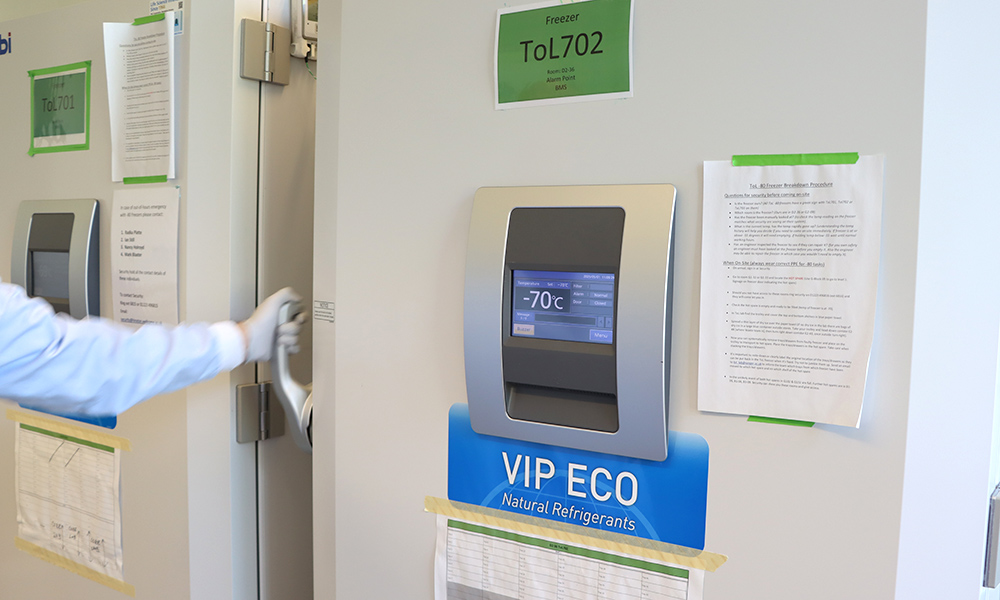

In order to produce a good quality reference genome, you need really large pieces of DNA, and they need to be super good quality. As soon as a cell dies, the enzymes in the cell will start to degrade the DNA. So, our gold standard is that samples are frozen as soon as possible after collection, either on dry ice or liquid nitrogen, to preserve the DNA molecules in as good a state as possible. Tubes will then go into a minus 70 degrees freezer until they are ready to be shipped here. Once this is done, our collaborators would then fill in the sample manifest and we would begin our compliance checks and accept the samples for shipping.

Tree of Life sample management simplified workflow. Image Credit: Shannon Gunn / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Click here for a written description of the workflow diagram.

Ian: We would only upload the manifest to our systems when we are sure that it follows the European Nucleotide Archive guidance for uploading genomic data.

Radka: This is to ensure that the information that ends up in the public domain and in our database is uniform, searchable and links to sequence data.

Nancy: We use a piece of bespoke software called STS, which stands for Sample Tracking System, to manage the samples. It allows us and the Legal and Research Governance team to check everything aligns before a sample is shipped. We see in the STS software four happy little green dots and a notification that says everything is in place and that the samples are ready to be sent. We get in touch with the partner and say we’re ready to receive their samples. This is when we give them our shipping address and work out how to ship them here. Once the courier is booked and organised, the samples will be taken from the freezer and put into dry ice. When they arrive, we scan the barcodes on the tubes and submit these data to STS which will do a check to confirm what we were expecting is what has arrived. We use STS again to sign everything off. Then, we store the samples in our minus 70 freezers and tell STS where they're stored, and finally, send them out to whichever pipeline is required. We mainly hand our samples over to the Tree of Life Core Lab team who do preparations before sequencing. We also have processes in place to manage samples that come in non-standard, non-barcoded tubes too – so we are able to accommodate what is needed to support the science.

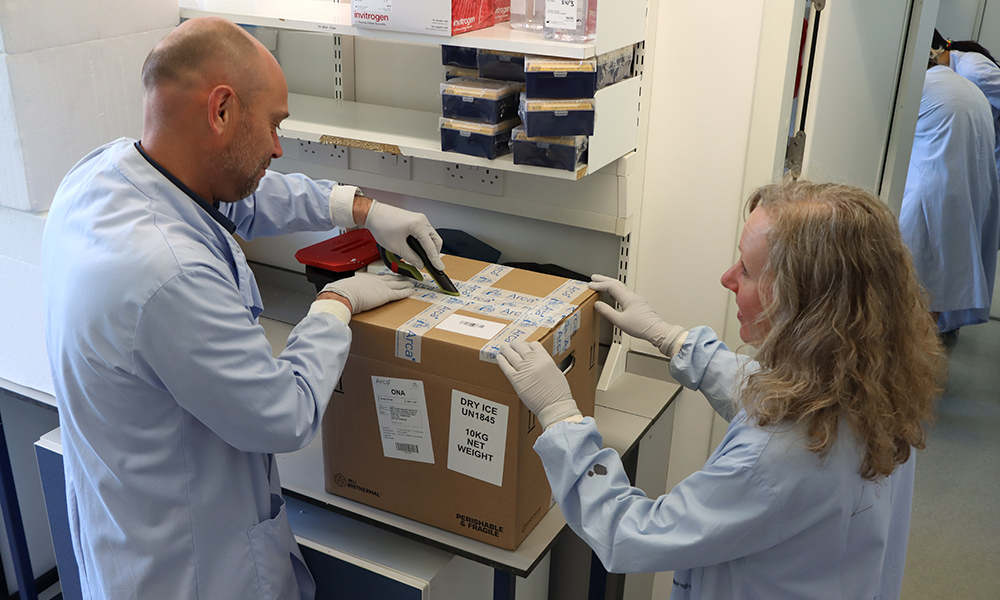

How the Sample Management team processes incoming Tree of Life samples. Please click on the images to discover more. Images credit: Mark Thomson / Wellcome Sanger Institute.

Have there been samples we have not been able to receive?

Nancy: There are some samples that we've just said we're not going to get because we either haven't got the permit or there are some ethical challenges. We have an ethics committee that will provide support and help to decide on whether a sample is brought in or not; I think that our ethics checks are exemplary.

What has been your favourite sample that we have received?

Radka: For me, it is the ones that have taken longer than expected to get; where the shipping discussions were taking months and months due to very complex permits and import and export licences being required, and we were still getting stuck. This was the case for a giant clam. In the end, it was the first genome sequenced for the ASG project, which is sequencing the genomes of symbiotic systems. It was an absolute nightmare to organise as we had partners in different countries. But once it arrived and we sequenced it, making it the first one in the ASG project, this became my favourite sample.

Nancy: I am fascinated by parasites, particularly parasitic worms, so I always enjoy receiving those!

Ian: There was a sample that a postdoc, Charlotte Wright, in our team was really excited to get. There's a really rare butterfly called the Atlas blue butterfly, also known as Polyommatus atlantica, that only appears on the top of the Middle Atlas Mountains in Morocco. It is one of those ones where you have to be in the right place at the right time. This butterfly has a huge number of chromosomes – over 200. I was happy because they were struggling to find it and get it here, but it arrived in the end.

What are some of the biggest challenges you face in sample management?

Ian: The Tree of Life programme has been generating data faster than ever before, producing a reference genome roughly every 48 hours. But in order to actually get the Genome Note out, which is the publication of the reference genome, you have got to assemble and curate it, and this can take a lot of time to complete. The programme has completed over 1,200 Genome Notes so far, so we’re not doing a bad job!

Nancy: Managing expectations of our partners can be a challenge; for us to understand their expectations and for them to understand ours is key. I think we must not only have our programme goals in our mind but must also think about the partner and their needs.

Radka: For this to succeed, establishing and maintaining good relationships is important, particularly for our partners who will be submitting multiple samples. When you build these relationships, sample submitters will know what to expect, and by the second or third manifest, they understand the process and are with you on the journey.

Nancy: Trying to efficiently store and track samples is a key challenge for us. From the Genome Notes we have published for completed species so far, there are still some samples left over. Part of the project design of our work is that any leftover samples will be archived in a museum or a repository. This may sound like an easy task, but it is actually really complex. Each sample that comes in is so different which makes the processes even more complicated. But we are learning as we go.

When I think back to the COVID-19 pandemic, when we had not long started bringing samples in, it was quite stressful. But we rode the waves and got all these processes in place as we learnt more and more. We now have developed Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and resources like email templates to make it easier for us and easier for our partners. We're going through the same story now with the archiving work. It is difficult, but the stuff we are learning we can then put into developing SOPs and processes so that it will eventually become quite easy.

Another challenge is supporting the Tree of Life staff to go out and collect their own samples as we don't solely rely on external collaborators sending samples to us. Sometimes the field work is on campus, sometimes it is local in the UK, but there are also Tree of Life team members going to the Amazon or to Australia. As a result, we have developed processes to support this including risk assessments and ensuring they've got the necessary equipment and logistics in place to undertake sample collection.

RELATED SANGER BLOG

Sequencing COVID-19 at the Sanger Institute

Amid the uncertainty, disruption and anxiety brought on by the pandemic, Sanger Institute scientists started a months-long mission to help tackle it. Go behind the scenes of the effort to sequence the genome of the COVID-19 virus at the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

How do we currently store our samples?

Nancy: Mostly in minus 70 degrees Celsius freezers! Historically, we've ended up with a lot of samples due to the number of large-scale projects we’ve been running. Over the past couple of years, an institute-wide project has been underway to deal with historical samples. With the number of samples we are receiving and will receive in the future, I knew we needed to ensure that we tackled this issue up front. In my experience, having an exit strategy for samples incoming is quite unusual, but a very good thing. We have had hundreds of thousands of samples, but we haven't got lots and lots of freezers. We try and keep that low for environmental and cost purposes.

Ian: Once we have generated all the sequence data, we don’t really need to keep the sample. If we haven't completed the project or we need to keep going back to a sample, we'll store it until the time is right.

How do we work with biorepositories to archive the samples?

Ian: We work with several biorepositories depending on the project. For example, when the DToL project was established, it was agreed in the process that samples obtained from Scotland would go to the National Museum of Scotland and everything else would go to the Natural History Museum in London. For the European Reference Genome Atlas (ERGA) project, which is an initiative coordinating the production of reference genomes for eukaryotic species in Europe, it was agreed that the samples would go to a biobank in Bonn, Germany.

Nancy: We also have scenarios where we receive samples from endangered species, which of course, are very precious samples. The agreements under which these samples are brought in sometimes note that on receipt of the sample, we own it, and anything left after sequencing we – in theory – can destroy. But we feel this is a terrible waste of such precious samples. Now, there is a potential partner in America who has expressed interest in obtaining some of these precious leftover samples, and we’re trying to figure out the compliance around this. We think this approach is more responsible than just throwing them away.

What would you want people to know about sample management?

Nancy: We usually have around 100 active ‘sets’ of samples at a given time. A set is anything from one to thousands of samples, so we juggle a lot. I think at times in the past the processes have seemed quite overwhelming and admin heavy, but we have finessed these and now have great turnaround times. For samples that are being shipped within the UK, from the point when the sample provider sends us the manifest to when the sample arrives here at Sanger, it is just two weeks. For stuff from overseas, it is eight weeks. That is pretty good and we’re proud of that.

Ian: We are here to help people through. If someone struggles with the manifest, we will help them with the mandatory columns and work with them to ensure we have the right information. So, sometimes we can end up doing a bit of the legwork to speed things up and help them along if they’re a bit unsure.

Nancy: Also, in the last year, within Europe, we have introduced a closed loop shipping system, so we reuse the shipment packaging boxes which we were previously putting out for recycling. We started it first in the UK but have extended into Europe. We did this as part of Project Psyche, a multinational effort to sequence the genomes of all 11,000 species of Lepidoptera – moths and butterflies – in Europe. For this project, we had clearly defined hubs, so it was predictable. We could send a list of locations to the courier and tell them what we needed them to do. The boxes were stored in the Netherlands and then shipped around. This has been a nice win!

As the number of Genome Notes increases, there is a demand for the sample management team to refine and implement processes that will make the sample to sequence process smoother. Their expertise is just one part of this pipeline but a necessary step that ultimately determines what genomes we end up with. No sample, no genome.

Proper handling, documentation, and storage of samples not only uphold scientific standards but also ensure that valuable biodiversity data is available for generations to come. Every sample we are lucky to receive is an addition to the biodiversity puzzle and we are excited to see what sample is next!

Find out more

- Tree of Life Sample Management team at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

- The Tree of Life research programme at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

- Darwin Tree of Life project

- Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics project

- BIOSCAN project

- Project Psyche

- Biodiversity Genomics Europe

- European Reference Genome Atlas

- Genome Notes from the Tree of Life programme