Image credit: Charlotte Cassie

In recognition of Endometriosis Awareness Month, we caught up with Charlotte Cassie, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, to highlight the gap in endometriosis research and how our work at the Sanger Institute is helping to fill this in.

Listen to this blog story:

Listen to "Five questions with Charlotte Cassie on endometriosis" on Spreaker.

It’s estimated that 54 per cent of people in the UK don’t know what endometriosis is, with this increasing to 74 per cent in men.1 Yet, 1.5 million women in the UK are affected by this condition – a number similar to that of diabetes or asthma.1

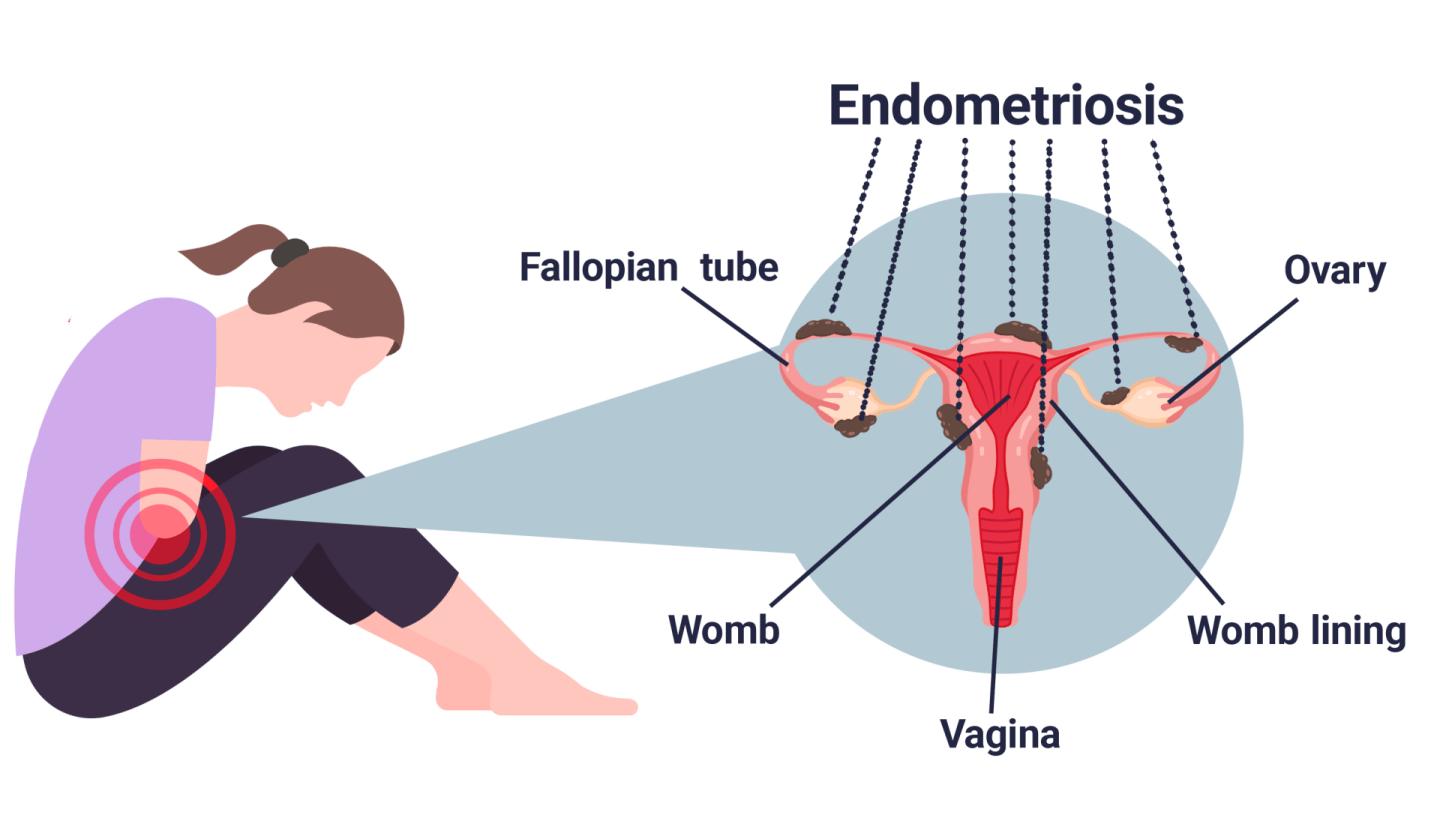

Endometriosis is a long-term condition where patches of cells that are similar to the ones in the lining of the uterus (womb), known as lesions, are found elsewhere in the body such as on the ovaries or other organs. These cells can grow and change in response to hormones released during the menstrual cycle, resulting in inflammation, pain and scar tissue. Most common symptoms include pelvic pain, pain during sex, heavy and painful periods, and infertility.

Potential locations of endometrial cells for women with endometriosis

Endometriosis Awareness Month in March aims to raise global awareness of this condition and its symptoms, as well as advocate for change. This year’s theme, ‘Endometriosis Explained’ hopes to emphasise the importance of public understanding of endometriosis and the need for healthcare professionals to better educate patients on their condition.

In recognition of this theme, we spoke to Charlotte Cassie who shared how ongoing research at the Institute is accelerating our understanding of endometriosis as well as her hopes for women’s health research in the future.

1. Why is studying the endometrium and endometriosis so important?

Over 30 per cent of women worldwide suffer from endometrial disorders such as endometriosis, infertility, and heavy and painful menstrual bleeding.2–4 Most endometrial disorders are currently poorly understood, which stems from a general lack of knowledge in the field on normal endometrial functioning. Our group at the Sanger Institute in the Cellular Genetics programme is trying to close this gap by undertaking extensive single cell profiling of the endometrium to unravel the different cell types and signalling networks across different menstrual stages of the endometrium. The endometrium is a highly dynamic tissue, where the lining is shed and re-grown on average 451 times across a woman’s lifetime; therefore, it is unsurprising how common it is for things to go wrong.5

Endometriosis affects approximately 10 per cent of women of reproductive age, which equates to 190 million women worldwide.6 In addition, endometriosis lesions are detected in up to 50 per cent of women seeking infertility treatment.7 Despite the high prevalence, so little is known about endometriosis. On average in the UK, it takes 8 years and 10 months for an endometriosis diagnosis to be made.8 Therefore, there is a huge research and medical unmet need for understanding endometriosis. With so many suffering from endometriosis, coupled with a lack of effective prognosis and treatment strategies, there needs to be a push in both the research and medical fields to improve this debilitating disease for women all around the world.

2. What are the current challenges surrounding endometriosis research and treatment?

Women’s health research has historically been underfunded, especially in comparison to other diseases with similar prevalences such as diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease.9 For instance, in 2022 in the US, Crohn’s disease research received $90 million in funding, equating to $130.07 per patient, compared to the equivalent $2 per patient received for endometriosis research.10 This lack of investment into endometriosis research has had damaging effects on endometriosis awareness and medical advancements.

The lack of research funding has resulted in a knowledge gap, with little known in the field

about basic mechanisms, such as how endometriosis develops. In addition, endometriosis is not a condition of somatic mutations, which are non-heritable genetic changes that happen during a person’s lifetime. The specific genes involved have not been identified, therefore it has been difficult to identify biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment. Currently, the only definitive diagnosis for endometriosis is surgical assessment, and with endometriosis symptoms being associated with other conditions, time to diagnosis is often too slow.3

What’s more, there is no cure for endometriosis; therefore, the limited treatment strategies available only aim to reduce symptoms. Hormonal suppressive therapies such as combined oral contraceptives are routinely prescribed. However, they are often ineffective in symptom management and come with a lot of side-effects.3 There has also been recent news of the approval of a hormonal treatment, called relugolix, for use on NHS England and Wales. While this provides another option for some patients where other treatment options have failed, this type of treatment again only addresses symptoms and not the root cause.

Surgery to remove endometriosis lesions has shown to decrease pain in some patients, yet this is highly debated, and five-year recurrence of endometriosis-associated pain is high.11–13 A hysterectomy is also often considered as a treatment strategy; however, this decision is irreversible and is associated with various complications alongside the fact it prevents future pregnancies. The limited treatment options, potential side effects and the possibility of recurrence highlight the need for more effective treatments that do not impact fertility or cause long-term complications.

3. How are we contributing to endometriosis research at the Sanger Institute?

I work in Roser Vento-Tormo’s group in the Cellular Genetics Programme at Sanger. This group has helped contribute to the field in recent years by generating comprehensive single-cell atlases of the endometrium.14,15 The atlases show how individual cells behave and change in different parts of the body (spatial) and over time (temporal). The endometrium is a highly dynamic tissue, consisting of two main compartments: epithelial, which are made up of cells that line surfaces, and stromal, which provide support and structure. Fibroblasts (a fibrous material making up connective tissue), immune cells and blood vessels populate the stromal compartment, and through signalling interactions with the epithelium, they regulate the proliferation and destruction of the whole endometrium during the menstrual cycle.4

Part of this work has identified macrophages in the uterus as key players in the process of endometrial proliferation – the renewal of the endometrium after menstruation.14 Furthermore, we have also identified key differences in these macrophages between healthy people and patients with endometriosis. Plus we’ve found an endometriosis-specific signature – a specific pattern of gene activity – in stromal fibroblasts, which might impair normal differentiation of the endometrium. This work was possible due to the large repository of tissue samples collected from both healthy individuals and those with endometriosis.14,15

In parallel, these tissue samples are also contributing to an ever-expanding biobank of organoids from the endometrium of both healthy individuals and endometriosis patients, with organoids being generated directly from endometriosis lesions. These in vitro organoid models can contribute to our understanding of endometriosis by allowing specific biological questions and changes to be studied at multiple time points and at a large scale that cannot be done in real patients.

4. What new tools are we using to understand the endometrium and endometriosis? And how do they better our research?

My research project aims to build upon current organoid in vitro models to better resemble their in vivo patient counterparts. To achieve this, we are bringing in the immune and stromal compartments, which the group previously identified to be important in normal endometrium homeostasis as well as endometriosis.14,15 We are in the process of applying single-cell RNA sequencing to these models at different stages of complexity and throughout hormonally stimulated menstrual cycle stages. We will then compare these in vitro models back to a large cohort of patient data to observe how representative our models currently are. The use of transcriptomic techniques, which analyse RNA molecules to understand gene activity, combined with machine learning methods will help identify new opportunities to improve our in vitro models, making them as representative as possible.

These in vitro models will help better our research as they will provide a scalable platform upon which research questions, endometriosis progression and drug screens can be addressed – something which otherwise would be impossible. Having a representative model for the endometrium and endometriosis will be important to help accelerate our understanding and ultimately close the research gap in this field.

5. What are your hopes for the future of endometriosis research?

My hope is that the research on endometriosis and other similar disorders gets the recognition that it truly deserves. In the past couple of years, there have been improvements in government funding for endometriosis; however, with the current reassessment of research funding in the US, there are growing concerns that funding contributions to women’s health research efforts will regress. Without funding, we cannot as a community fund the necessary advancements so desperately needed for improving understanding, diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis.

On a more general level, I hope that endometriosis awareness is increased across all sectors and that those with endometriosis can be assessed and treated without diagnostic delay or the fight for healthcare professionals to take their symptoms seriously. Before starting my Postdoc at the Sanger Institute, I was naively unaware of how large the prevalence and detrimental effect endometriosis has on so much of the population. I hope by increasing the exposure to this debilitating disease, patients can be treated with the seriousness and respect that they so need.

To try and help increase awareness of endometriosis and associated gynaecological conditions, the team and I have created The Gynaware Project. Through this, we have been working on an informative leaflet, with the help of illustrators, to spread understanding of common and uncommon gynaecological conditions, and ultimately reduce stigma surrounding them. In January of this year, we also ran a screening of the endometriosis documentary, Below the Belt to help raise awareness of the impact of the condition on patients. We hope to continue to run other events in the future to help encourage conversations surrounding this stigmatised condition.

There are so many talented researchers globally working on endometriosis and hopefully with the proper investments and awareness, great progress in endometriosis research can be made. This will hopefully open doors for research into other, even more underfunded gynaecological conditions and start to close the inequality gap in women’s health research and treatment as a whole.

Find out more

- Endometriosis UK website

- Vento-Tormo research group at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

- Marečková M, et al. An integrated single-cell reference atlas of the human endometrium. Nat. Genet. 2024; 56: 1925–1937.

References

-

- Endometriosis UK. Press Release: Endometriosis Awareness Month. [Last accessed: March 2025].

- Filby CE, et al. Cellular Origins of Endometriosis: Towards Novel Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2020; 38: 201–215.

- Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2020; 382: 1244–1256.

- Vannuccini S, et al. From menarche to menopause, heavy menstrual bleeding is the underrated compass in reproductive health. Fertil. Steril.. 2022; 118: 625–636.

- Chavez-MacGregor M, et al. Lifetime cumulative number of menstrual cycles and serum sex hormone levels in postmenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res. Treat.. 2008; 108: 101–12.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Fact sheets: Endometriosis. 2023. [Last accessed: March 2025].

- Meuleman C, et al. High prevalence of endometriosis in infertile women with normal ovulation and normospermic partners. Fertil. Steril. 2009; 92: 68–74.

- Endometriosis UK. Endometriosis UK diagnosis survey 2023 report March. [Last accessed: March 2025].

- Sims OT, et al. Stigma and Endometriosis: A Brief Overview and Recommendations to Improve Psychosocial Well-Being and Diagnostic Delay. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021; 18: 8210.

- Kirk UB, et al. Understanding endometriosis underfunding and its detrimental impact on awareness and research. npj Women's Health. 2024; 2: 45.

- Ellis K, Munro D, Clarke J. Endometriosis Is Undervalued: A Call to Action. Glob. Womens Health. 2022; 3: 902371.

- Dunselman GA, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014; 29: 400–412.

- Horne AW, et al. Surgical removal of superficial peritoneal endometriosis for managing women with chronic pelvic pain: time for a rethink?. BJOG 2019; 126: 1414–1416.

- Guo SW. Recurrence of endometriosis and its control. Hum. Reprod. Update 2009; 15: 441–461

- Garcia-Alonso L, et al. Mapping the temporal and spatial dynamics of the human endometrium in vivo and in vitro. Nat. Genet. 2021; 53: 1698–1711.