Birth cohort studies offer rich information about populations, helping to guide key decisions in areas spanning health research to social policies. For the first time, researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute have sequenced rich genomic data from three birth cohort studies, which could unlock new insights into human health and disease. Here, we explore the benefits of population research and how combining genetics with population data could impact how we tackle health problems.

Listen to this blog article:

Listen to "Sequencing decades-long population data unlocks health insights" on Spreaker.

The power of population research

Scientists who study populations are interested in tracking groups that share similar characteristics, such as people, plants or animals. Most real-world populations are collectively too large to study, for example, 'all women in their 30s living in the UK', so scientists use a representative sample of their target population to explore instead.1

Population research can provide valuable observations into a population’s patterns, trends, and dynamics. This knowledge can help inform diverse areas, such as economic policies based on an ageing population, or tracking the spread of certain diseases.2

When researchers study a population, they sometimes use a cross-sectional study, which examines groups of individuals at a single point in time, such as the genetic differences among smokers across different age groups. Alternatively, they can use longitudinal studies, which follow the same group of people and measure how they change over time.

A birth cohort study is a type of longitudinal study that follows people throughout their lives. These studies, which may even include participant’s children and grandchildren, capture vast amounts of phenotypic, genetic, environmental, lifestyle and health data. These data enable researchers across disciplines to study complex relationships between genetics, environment, and behaviour. This includes:

- Medical research – such as identifying disease risk factors by tracking how they develop over time.

- Social science education – family dynamics, and workforce participation.

- Economics – productivity data, health expenditures, and societal costs of illness.

- Environmental science – understanding how environmental exposures, like pollution, affect health.

Early this year, Sanger Institute researchers published a peer-reviewed, open-access data note3 detailing high-quality genetic sequence data from three leading UK population-based birth cohort studies: the Millennium Cohort Study, Born in Bradford, and the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (see below for more information). The Sanger Institute is working with other UK research institutes to combine data from these population studies to reveal new population-based insights.

Why is this genetic information useful?

Researchers, led by Professor Matt Hurles and Dr Hilary Martin at the Sanger Institute, sequenced the genomic data last year. They used whole exome sequencing, a technique focused on protein-coding regions (exons) which comprise around 1 per cent of the human genome.4 Sequencing exons is a cost-effective way of searching the part of the genome in which genetic variants tend to have the largest impact on diseases and traits. It is especially helpful for studying rare genetic diseases.5

The exon data has been sequenced for around 25,000 children and 13,000 parents across the three birth cohort studies. The exome dataset, combined with the rich phenotypic data, offers insights that cannot be gleaned from larger, less detailed datasets. The exome data are freely available in the public European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA) database. The combined birth cohort information and exome data help create a detailed picture of UK health, disease and lifestyles. More information about the data note can be found in our recent news article: Largest ever DNA sequencing dataset on UK child development studies available.

In the UK, birth cohort studies are coordinated by Population Research UK (PRUK), an initiative that connects longitudinal population studies to make the data easier to access and use across social, economic and biomedical science. PRUK worked in partnership with the Sanger Insitute and birth cohort studies to lead the exome data publication. The Sanger Institute researchers are currently sequencing more cohorts, such as the Fenland Study, the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study (MoBa), and the South African Drakenstein Child Health Study.

RELATED SANGER NEWS

Largest ever DNA sequencing dataset on UK child development studies available

For the first time, large-scale DNA sequence data on three UK long-term birth cohorts has been released, creating a unique resource to explore the relationship between genetic and environmental factors in child health and development.

New population insights from rich genomic data

Dr Hilary Martin, Group Leader at the Sanger Institute, studies medical and population genomics. Her team is already using the exome sequencing data, combined with the other information from the birth cohort studies, in their research.

For example, PhD student Daniel Malawsky is exploring how genetic differences may affect the development of children’s cognitive skills, such as memory and problem-solving, as they grow. The team analysed data from around 6,500 unrelated children from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC, see boxes above) to investigate links between common genetic changes, school success and adult cognitive skills. The study, which has not yet been published, is designed so they can separate the direct impact of genetics on children from influences such as different parenting styles which may also be correlated with genetics.

In another project, the team is investigating how genetic variants may relate to behavioural traits and mental health conditions.

“This is one of the largest exome sequencing projects to date, marking the start of a golden era in understanding human development. These data will uncover vital insights into human health and disease based on the UK’s world-leading birth cohort studies. At the Sanger Institute, we recognise that large-scale genomic data are crucial for advancing science, and by making it openly accessible, we hope to empower the entire research community and ultimately drive significant societal impact.”

Professor Matthew Hurles,

Director and Senior Group Leader, Wellcome Sanger Institute

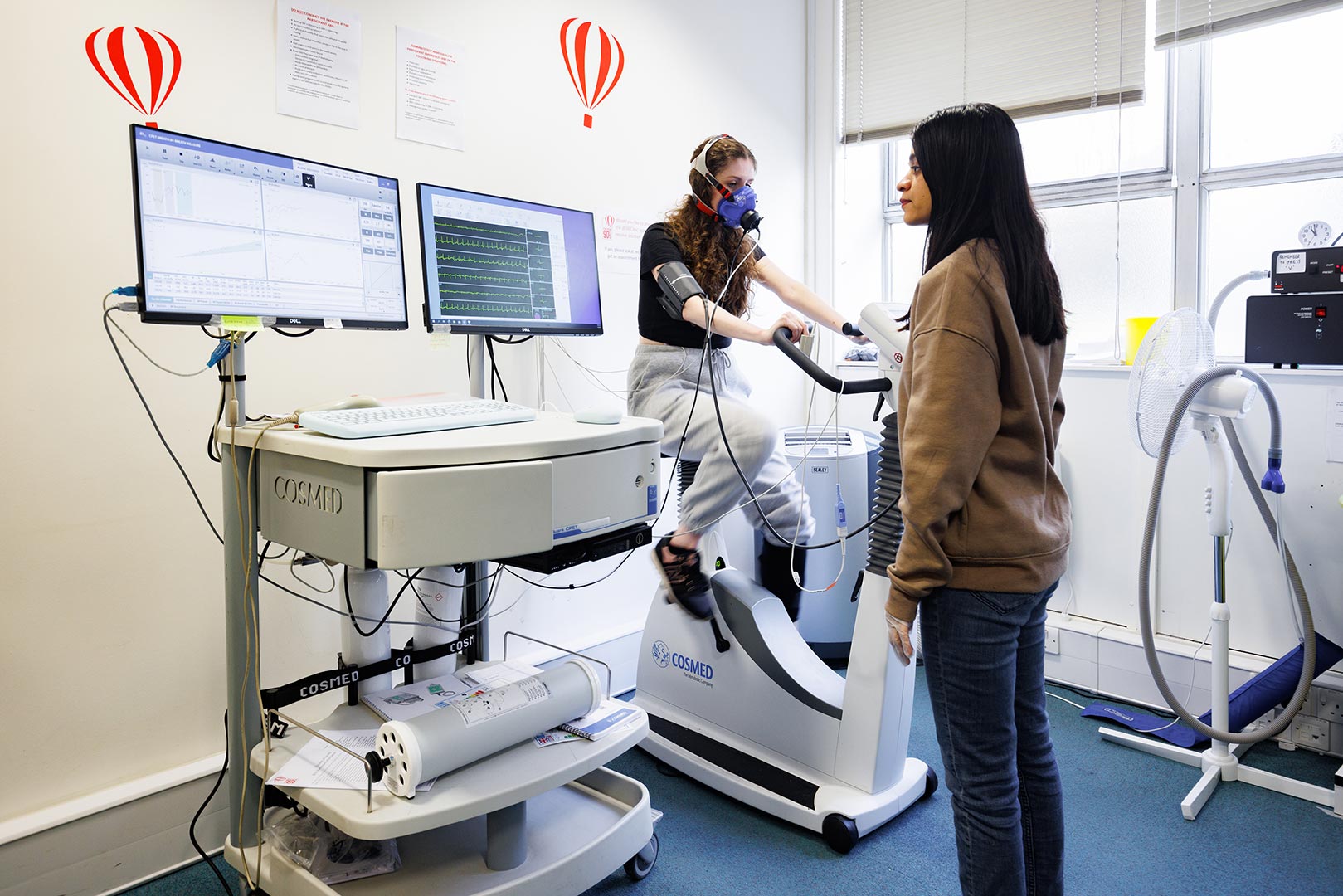

Photos of participants and researchers taking part in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, also known as Children of the 90s.

The future of population-based data across the UK

Professor Nicholas Timpson is the Co-Director of PRUK and also heads a research group at the University of Bristol investigating how genetics and lifestyle impact health. Professor Timpson leads the ALSPAC birth cohort study and spoke to us about the importance of these population-based studies and the value of exome sequencing.

“In the UK, we have several of the longest-running birth cohort studies, with some spanning over three decades. We benefit from high participation rates and together the studies capture important diversity in the UK across ethnic, geographic and socioeconomic differences.

Longitudinal population studies offer a unique opportunity to explore important health questions. By combining data across studies, we can spot patterns that are impossible to see in smaller groups, helping us understand common events such as living with obesity as well as rare diseases. None of this would be possible without the generous commitment of study participants, who have contributed their time and personal information for decades. As scientists, we are responsible for ensuring this research is impactful and transparent for everyone.”

Professor Nicholas Timpson,

Professor at the University of Bristol, Principal Investigator at ALSPAC and Co-Director of PRUK

During Professor Timpson’s career, he has witnessed significant advances in genomic technology, including the rise of next-generation sequencing. Within population research, he believes we have already achieved so much with genomic data, whereas there are significant opportunities to improve how we measure health indicators. Most health measures are simple proxies of the condition scientists are interested in. A classic example would be blood pressure. It is taken as a single measurement, but in reality, it represents a combination of factors including the heart, vasculature and blood consistency. This works fine for making predictions, but it cannot capture the biology behind the measurement.

“The future of this research lies in linking genetic data with deeper, more precise health measures of complex traits such as cardiovascular health and metabolic function. As technology advances, we’ll be able to uncover new insights into how genes interact with lifestyle and environment, potentially leading to better treatments and policies.”

For ALSPAC, the participants who joined the project as babies are now around 35 years old and many are having their own children. There are ongoing opportunities for researchers to study the impact of genetics and environment on their various life stages, from child development, puberty, fertility journeys and onwards as they age. Research questions need to combine biological knowledge with social science. For example, it has been shown that educational attainment is highly heritable.6 However, the situation is complex, and changes to the school environment and approaches to education may have an impact. This shows how understanding genetic and environmental interactions might influence educational policy.

The exome data sequenced by the Sanger Institute researchers using these birth-cohort studies provide a unique opportunity to unlock new information about human health and disease across the UK. These data open endless possibilities to explore new questions across diverse research areas, from biology to social science. This includes the opportunity to tackle big health challenges such as obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease using new treatments and precision medicine, as well as guiding social and economic policies. Nonetheless, future research must focus on improving health measurements and continuing to collaborate across disciplines. By sequencing datasets from countries and communities outside of Europe, researchers will also increase the genetic diversity in longitudinal studies.

Funding Statements

- The Millennium Cohort Study is core funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and a consortium of government departments.

- Born in Bradford is funded by external funders such as the National Institute for Health Research, National Research Councils, and Wellcome.

- The Children of the 90s study (also known as the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; ALSPAC) receives core funding from the UK Medical Research Council (MRC), Wellcome and the University of Bristol and additional support from many other funders for individual projects.

- PRUK is a collaborative initiative funded by the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Infrastructure Fund, specifically through ESRC and MRC.

References

- Understanding Health Research. Populations and samples. [Last accessed: February 2025].

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Population and Epidemiology Studies. [Last accessed: February 2025].

- Koko M, Fabian L, Popov I, et al. Exome sequencing of UK birth cohorts. Wellcome Open Res 2024; 9:390.

- Marian AJ. Sequencing your genome: what does it mean? Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2014;10:3–6.

- NHS England. Whole exome sequencing. [Last accessed: February 2025].

- Krapohl E, Rimfeld K, Shakeshaf NG, et al. The high heritability of educational achievement reflects many genetically influenced traits, not just intelligence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; 111:15273–15278.