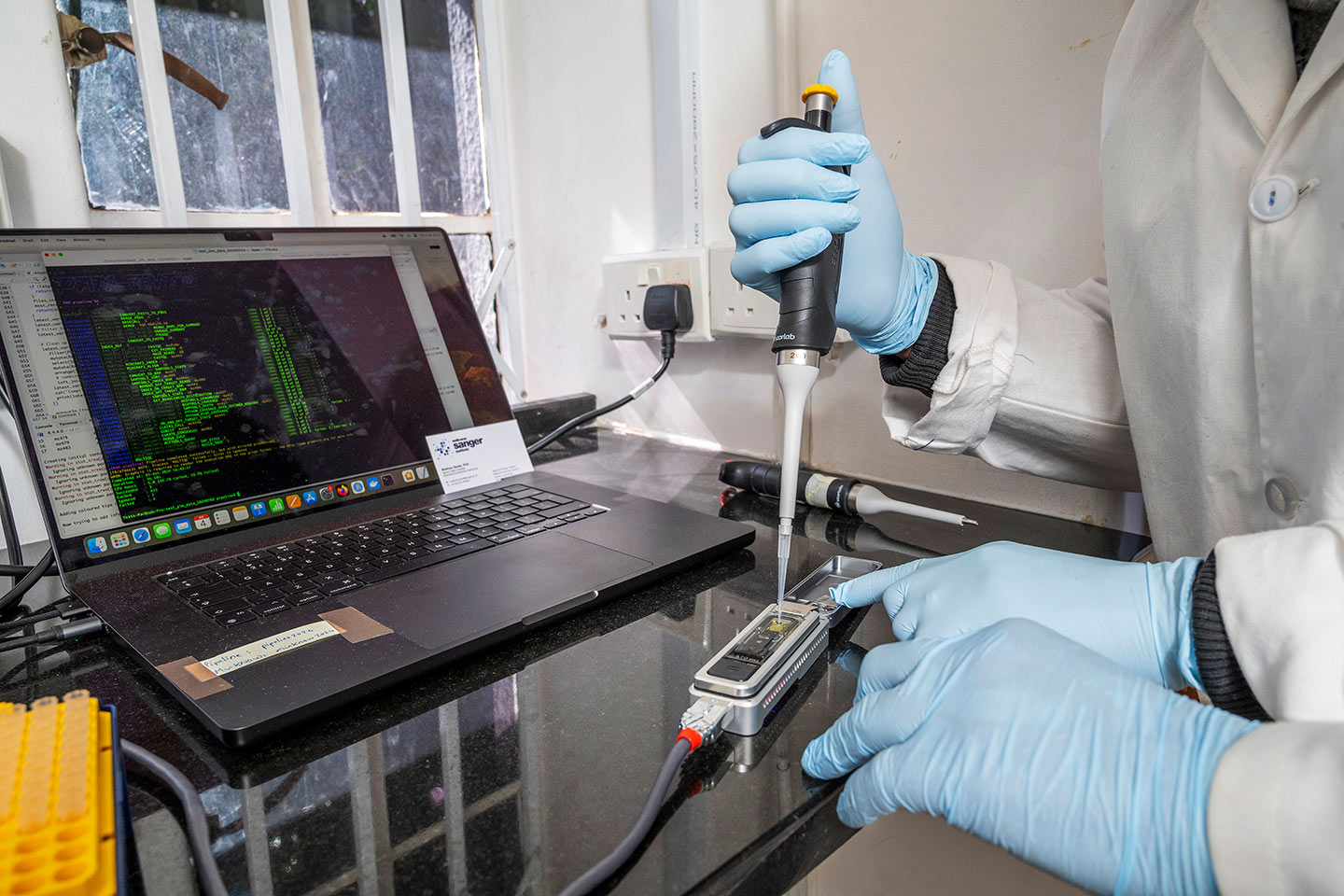

Image credit: Chris Scott / Wellcome Sanger Institute

Syphilis may be known as the ‘forgotten disease’, but in reality, it is making a comeback as cases rise around the world. Researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and their international collaborators in Africa are working to enhance existing syphilis datasets. Diversifying data can help enable the design of novel vaccines as well as detect and track the spread of the bacterium to prevent further transmission.

Listen to this blog story:

Listen to "Syphilis surprises with a worldwide comeback" on Spreaker.

Rising cases of syphilis worldwide

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. If detected early, syphilis can be treated with antibiotics. However, some individuals infected by T. pallidum can be totally unaware because of how the symptoms present.

The ‘great imitator’ is one of many names historically given to syphilis and one that still remains accurate. Syphilis is difficult to identify during early stages of disease when the symptoms range from non-existent to rashes and sores. People are less likely to seek help if their symptoms are mild, which can result in them unwittingly transmitting the disease through sexual activity.

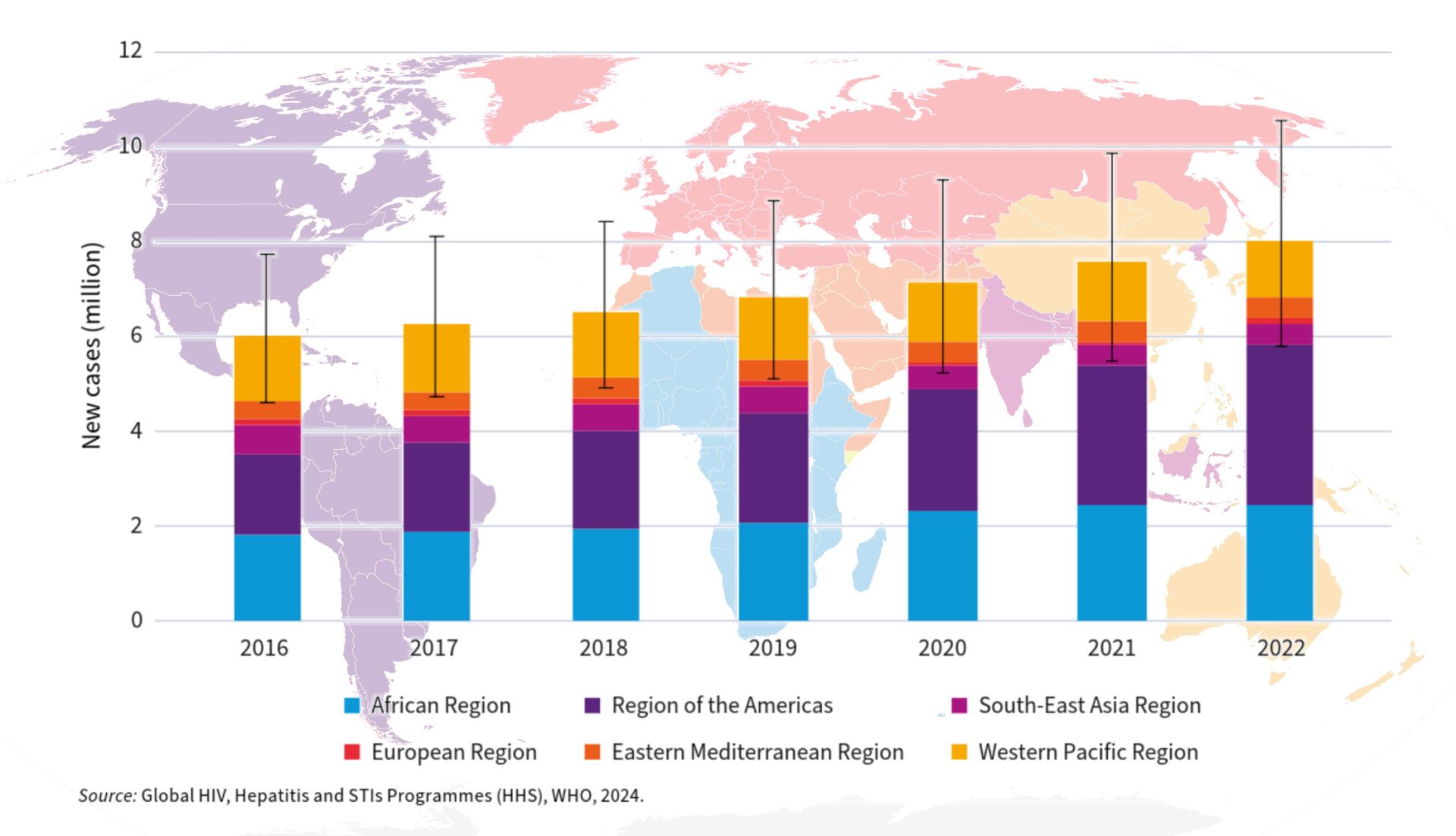

Another common name for syphilis is the ‘forgotten disease’, which has now become misleading due to its increase in prevalence around the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that eight million adults aged 15–49 acquire syphilis globally each year.1 In 2022, there was an estimated 700,000 cases of congenital syphilis globally.1

WHO-Rise-of-Global-Cases-of-Syphilis

Estimates of the number of new cases of syphilis among people aged 15‒49 years, by World Health Organisation (WHO) region, 2016‒2022. (Adapted from https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/stis/strategic-information )

The rise in cases is particularly prominent in many high-income countries. According to the UK Health Security Agency, rates in the UK are currently at the highest since the Second World War.2

UKHSA-Syphilis-diagnoses-in-UK-100-years

Reproduced from UK Health Security Agency Blog article: STIs through the centuries. https://ukhsa.blog.gov.uk/2024/03/13/stis-through-the-centuries/

So, why are syphilis cases on the rise? One reason could be that changing behavioural practices in high-income countries has resulted in increased numbers of sexually transmitted diseases – including syphilis.

Funding gives a boost to syphilis research

To better control the spread of syphilis, scientists first need to understand it – what it looks like internationally, what mutations it may have gained to evolve human defence mechanisms and what antibiotic-resistant mutations may be circulating.

But to understand this, scientists need a large dataset that reflects the different genetic variants of the bacterium found in patients around the world. This dataset will also provide us with information about genes that could act as targets for future vaccine development.

Understanding how these genes vary can ensure that any vaccines in development can target all strains of syphilis, not just the ones most common in certain countries.

In 2021, the Sanger Institute researchers and collaborators won multi-year funding from the Gates Foundation to build a more equitable dataset to inform vaccine development for syphilis. The aim of the project was to assess syphilis strain diversity in Africa and to build partnerships between the Sanger Institute and researchers from institutes across Africa.

Joining forces with local experts, researchers started recruiting patients in 2022 and gathering samples to test.

RELATED SANGER INSTITUTE ARTICLES

Collaborative research exchange

During the three-year Gates Foundation grant, researchers and clinicians collected over 1,100 patient samples from across Botswana, Ghana, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

Syphilis-sampling-in-Africa

Total numbers of genital ulcer patients recruited from across Botswana, Ghana, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. Image credit: Mathew Beale / MAGUS Consortium

On a recent research trip to Zimbabwe, Dr Mathew Beale and Dr Vignesh Shetty from the Sanger Institute worked closely with clinical scientists at the Biomedical Research and Training Institute (BRTI) in Harare to process patient samples to detect and sequence syphilis.

The researchers utilised patient samples from Zimbabwe who were presenting to sexual health clinics with genital ulcers. From this, they were able to detect and sequence T. pallidum in the lab using a new, cheaper technology that involves PCR probes. The benefit of this technology is that it can be applied in labs with fewer resources and if adapted, could also be amenable to detecting other infectious diseases.

By working together, the team was able to provide extensive on-the-job training to researchers who were new to this sequencing equipment, creating the next generation of regional experts. They also addressed ways to try and maintain lab work around power outages, which can be an ongoing issue in some labs.

It takes roughly two days to sequence and test a sample of T. pallidum under optimal conditions. However, during the visit, Harare was experiencing daily power outages which interrupted and delayed this process. Mathew, a Senior Staff Scientist at the Sanger Institute, said: “A key learning point was that we need to consider technologies which can run entirely on backup batteries – this method can easily be adapted to do this.”

Vignesh, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Sanger Institute, highlighted that the approaches tested in Harare on syphilis samples served as a proof-of-principle for methods that could be applied to almost any infectious disease-causing bacterium. He noted that these methods not only demonstrated their field adaptability but also showed great promise as tools for use in low-resource countries.

He valued the opportunity to provide training and support to researchers in-country to help build strong collaborations between the Sanger Institute and BRTI researchers. Vignesh noted, “In Zimbabwe, I was inspired everyday by research happening in the labs. It was great to be a part of training clinical scientists to master new laboratory techniques to improve detection and disease tracking – not just of syphilis, but other diseases of interest such as HIV.”

The future for syphilis research

The outlook of this research, and its ability to contribute to downstream preventative vaccine or treatment developments will depend on further funding investment.

Mathew said, “The Gates Foundation funding has given us an invaluable opportunity to steer a multi-country collaborative effort to work with local researchers and clinicians across Africa. There has been a huge amount of bi-directional learning between collaborators across clinics and labs, which has allowed us to test methods in a variety of different settings.” Utilising these established collaborations will be important for future syphilis research projects.

The future of funding for a syphilis vaccine may be uncertain, but research towards producing equitable vaccine candidates has advanced thanks to researchers from the Sanger Institute and across Africa joining forces to collect, sequence and study samples from Botswana, Ghana, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

The data obtained is now a new and evolving resource that combines African and non-African syphilis data. The hope is for this equitable resource to then be leveraged to design and build a vaccine to protect future generations from syphilis.

Whilst a syphilis vaccine is the end goal, developing one that is ready to be used in humans may be years away. In the meantime, researchers at the Sanger Institute have been designing diagnostic tools to detect syphilis that can be used in a wider variety of locations with limited infrastructure. The hope is that further funding can drive research forward towards a vaccine and bring an end to the lengthy battle against this disease.

Find out more

References

- World Health Organisation website. Factsheet: Syphilis. Accessed on 15 February 2025.

- UK Health Security Agency Blog article: STIs through the centuries and Sexually transmitted infections (STI) annual data, UK Health Security website (updated on 17 july 2024)