Alix and Pip enjoying a day out. Photograph used with kind permission of Clare Millington

Some of the conditions may be familiar, like Huntingdon’s disease or cystic fibrosis, which affect thousands in the UK. Others affect just a handful of people in the world.

Clare Millington is mum to identical twins Pip and Alix, who have an extremely rare condition. They have difficulties with communication, sensory integration and movement. Alix also has type-1 diabetes. When they were younger, most of the girls’ hospital appointments were focussed on helping them with their symptoms.

Clare talked to us about her experiences.

"I was a little uncertain to start with when people started talking about learning difficulties whether that was a diagnosis in itself. It wasn’t really clear that wasn’t a diagnosis, it was just what manifested.”

The girls were 10 when their paediatrician in Newcastle suggested they join the Deciphering Developmental Disorders (DDD) study - to see if a genetic cause of their difficulties could be identified. They signed up and saliva samples were sent away for DNA analysis. Clare was busy, working and looking after the twins, and didn’t think more about the study until a letter came through the post four years later.

“We were told they had a DDX3X mutation and were handed a learned paper, which had been published just a month before. It was quite amazing to think they had found what had caused most of the girls’ difficulties.”

The diagnosis has had a huge impact on Clare’s family. They contacted the newly formed DDX3X foundation in America, and have connected with other families with the condition in the UK. Clare described how meeting others has been an amazingly positive experience.

"Previously we were on the sidelines. We’ve belonged to some cerebral palsy groups but we don’t quite fit. We’ve belonged to some communication aid users groups, but again, we’re the odd ones out. We were always welcomed but they weren’t like the other children.

"To have a support group of parents that totally identify with you is huge. You may not see each other or talk to each other often, but you do belong.”

There are now a total of just 250 girls in the world identified as having DDX3X Syndrome, though researchers think there are likely to be more. It’s clear that the condition is a spectrum, with some much more severely affected than others. But there are similarities between the girls too - and knowing about those can help with treatments.

“A lot of the girls have cortical visual impairment – their visual acuity is good, but actually the processing of the visual information is so poor that they are visually impaired.

"That’s very hard to pick up in a child with learning difficulties, because doing a sight test is tough. But once you know that it’s a common part of the condition, you can look for it. And think, maybe that’s the root reason they’re not learning to read or recognise shapes.”

Another common issue is constipation, which affected the twins too. At first, their inability to get potty trained was put down to their learning difficulties. But once people realised that there may be an underlying structural problem they looked further. It was found they have virtually no gut transit – this means the muscles in the gut aren’t working to move food along. Their treatment was changed.

"Knowing this helps them have a healthy life. Now we’re getting a treatment that actually works – because we know what the problem is. There is more research all the time, leading towards ways of getting good treatments.”

"I really think that the twins would be very much side-lined without their diagnosis. I really don’t think we would have moved forwards on many of the issues that they have without a diagnosis.”

Diagnosing thousands

Pip and Alix are two of over 13,600 children who joined the DDD study, which started eight years ago. Researchers at the Sanger Institute have been working with NHS clinical genetics services across the UK to identify, catalogue and analyse gene changes that may be responsible for a whole range of developmental disorders. None of the participants had a diagnosis before they joined the study.

Now, all the participants’ data have been analysed and reports are being passed back to their clinical geneticists. The DDD team have found diagnoses for about a third of the children. They are committed to re-analysing the data to try to find a diagnosis for as many of them as possible.

Dr Helen Firth, Consultant Clinical Geneticist at Cambridge University Hospitals Trust, and Honorary Faculty at the Sanger Institute, is one of the founders of the study. She described how new knowledge means they can continue to make new diagnoses.

"We’ve been re-analysing at regular intervals through the project. On our first thousand patients we achieved a diagnostic rate of 27 per cent. Three years later when we re-analysed the same data, with new knowledge, we can lift that diagnosis rate to 40 per cent. That’s based on genes we’ve discovered, and based on genes others have discovered and putting those into the mix. Plus, there are new tweaks to the pipeline - things that we’ve learnt to improve; the way we are filtering the data.”

The team expect the pattern to continue as the project runs until 2021.

Navigating the new ethical questions

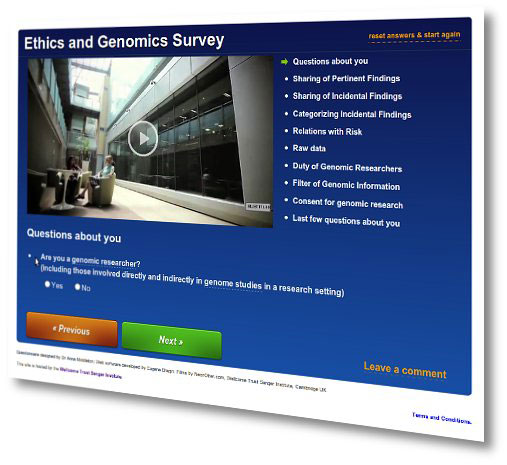

The study was one of the first of its kind in the world, looking at whole exome sequences of participants. It raised ethical issues, which were carefully considered from the outset, with the help of Professor Michael Parker and Dr Anna Middleton.

One of those questions was around ‘incidental’ findings. These are findings not related to the developmental disorder, and not looked for, but they could be important to the participant. For example, a mutation that increases the risk of developing cancer could be identified in someone’s DNA sequence. After careful consideration and consultation, the DDD team decided not to return these findings, should there be any, but to explore what kind of information people would want from such genome sequencing.

The DDD ethics team gathered the views from ~7,000 people from 75 different countries. They found that most people are interested in receiving genomic data, though not at all costs, particularly if it potentially compromises the ability to conduct research.

Bringing together the views of the public, patients, participants, clinical geneticists and researchers has shaped the debate in the UK and internationally. It has also set a strong precedent for similar projects, as genome sequencing becomes more widely available.

The future

Diagnosis by the DDD Project has transformed the lives of Alix, Pip and their family by helping them to connect with other families with the same condition. Photo kindly provided by Clare Millington

A diagnosis doesn’t always change anything practical, like it did for Pip and Alix, but it is still important. Many families talk of a relief of finding out the cause of a condition. The diagnostic odyssey and years of testing are over.

DDD has over 200 associated research studies. These groups and collaborators are investigating the data to understand more about the conditions and the genes that cause them. 125 research papers have been published so far. Mutations in hundreds genes have been identified and 49 new conditions described.

Helen reflected on the eight years of the study.

"We’ve had the great good fortune to have excellent support from clinicians, scientists and families within the NHS. To bring those people together with the world-class team of scientists at the Sanger Institute has driven the study. It’s exceeded expectations. We’re continuing to discover new things using this data.”

"It really is a gateway. Once you can find what the genetic basis of these conditions is, it unlocks a lot of opportunities going forward.”

The team continue to open up these opportunities so that they can help more children like Pip and Alix.

As we move into the next medical era, genomics will be a foundation stone for many. Enabling research into some of the rarest conditions in the world now, will bring new options in the clinic for the patients of the future.

With thanks to Clare Millington for sharing her story

Find out more

For support on living with a rare condition, contact Rare Disease UK

Recruitment for DDD has now ended. See their website to find out more about the study

Read more about the project's eight years on the Sanger website: Milestone reached in major developmental disorders project