Image credit: Mark Thomson / Wellcome Sanger Institute

Dr Omer Bayraktar takes us on a journey through the intertwining of his life and science – a journey that spans continents and generations to shape new scientific narratives about one of our most complex organs: the brain.

Listen to this blog story:

Listen to ""Learning new things takes time": Omer Bayraktar on the beauty of neurobiology, changing fields and creativity in science" on Spreaker.

Scientists can sometimes be depicted as lab coat wearing recluses, who from childhood are running experiments in their basement. But for Dr Omer Bayraktar, Group Leader in the Cellular Genomics programme at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, his initial interests were more aligned with the humanities.

Growing up, Omer’s father was a physician, his mother an opera singer and his aunt a molecular biologist. Despite this influence, Omer initially wanted to become a journalist due to his love of literature and desire for creativity. It still baffles him today as to how he ended up in science as he initially lacked “the science bug”.

However, during his teenage years, Omer went to a science-focussed high school, which he admits had terrible humanities education. He began getting good results in his mathematics and biology classes, which made him feel like a good student and ultimately, was the beginning of his journey in science.

“I just had an affinity for it, even at that time, I can’t explain it. I just liked it… I think I had this idea of what a cool biology researcher would look like, and I wanted to be that.”

Sitting across from me in his office on a regular Thursday afternoon, Omer radiates just that. Despite just finishing another meeting, Omer’s energy and engagement in the conversation does not falter.

Omer’s group is currently in the process of analysing and releasing new data from their recent work. They are focussed on using large-scale, advanced genomic techniques to explore human brain cellular diversity. The team has just published a new tool called cell2fate that can help map the origins and journeys of cells in development and disease.

While this tool maps cell journeys, here we map the origin and journey of Omer’s life, which started in Turkey. When deciding on his next steps after high school, Omer told his parents he wanted to study molecular biology and genetics at the Middle East Technical University (METU) in Ankara, Turkey. Like many traditional parents, they had questions: “What will you be doing? What kind of job will you get?”. Now, as a parent himself, Omer understands that his grandparents pressured his father to become a doctor when he was growing up. Omer is grateful that despite this, his parents ended up supporting him with his decision.

As his father was an American, Omer was fortunate enough to have a strong understanding of the English language, which is broadly taught in Turkey. This allowed him to read early scientific textbooks on his own, including one on the molecular biology of a cell.

“I was just hooked, and I knew that was going to be the rest of my life. Old school molecular biology got me.”

During his time at METU, Omer had to complete at least one summer internship to graduate. At this time, he was particularly interested in RNA splicing, a process which involves cutting out and rearranging sections of messenger RNA (mRNA).

“I thought it was really cool that you have the central dogma, but there is this little blip in it, and the mRNA messages that are generated from the blueprint in the genome need to be edited with splicing to get rid of the ‘junk’.”

After sending out loads of emails, Omer managed to get a position in Professor Alice Barkan’s lab at the University of Oregon. However, at the time, Alice did not have the funding to cover Omer’s visit, and as he was not a citizen of the US at the time, he was not eligible. But Omer’s gut told him to not give up. Using money from his own pocket and the support of his parents, Omer took the plunge and headed to the other side of the world.

“I knew it was my ticket. It was the ticket to the rest of my career. It was an incredible thing to have that one step open so many doors. If I didn't take that opportunity, I would 100 per cent not be here.”

Spending the summer in Oregon, Omer got hands-on experience in the lab trying to understand RNA splicing in the maize plant. This work eventually was published, giving Omer his first research paper authorship of many to come.

By the end of university in 2008, Omer knew the lab was where he was meant to be, and admits that he began to check out of the theoretical classes, which saw his grades begin to slip.

When applying for graduate programmes, Omer knew that he would need to move abroad for more research opportunities, so sought to get a green card through his father. He then optimistically applied but got rejected from several Ivy League schools, which he now appreciates was the wrong move considering his grades. As another option, Omer also applied back at the University of Oregon. However, in the midst of a financial crisis, the university had no funds to support foreign students, and it relied on the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) to fund stipends for people granted residency.

Despite his green card, Omer’s application was dismissed as he was a resident of Turkey. His previous principal investigator, Alice, had to drag his application out of the pile and plead his case – a career defining moment for Omer: “she saved me”.

This led to a five-year PhD in a new country and Omer was excited for his new adventure. Despite feeling isolated at times, being the only international student in his programme, Omer remained focussed on the science and nothing else. Upon reflection, he explains how at the time he dwelled on the social situations or references he did not understand, rather than the value that his international background brought to the table.

“I think it would have helped me to see more of those with a similar background to me in these spaces. When I moved to San Francisco later on, and here at Sanger, I was and have been able to relive that part of my life, which is important.”

As part of his PhD programme, Omer undertook three rotations in his first year – each providing him with a unique insight into cellular life. Omer described his first rotation as a “mini-PhD” in itself. He explored gene expression in chloroplasts, which perform photosynthesis, and uncovered protein ‘caps’ that protect RNA transcripts from being degraded.

“It was great to be a part of this story. It was really beautiful. This is when I realised that this is how you write textbooks. This is how you can have a foundation of understanding of something you did not before. This is what still drives me and the team today, creating foundational knowledge and approaching human brain diseases through a lens of fundamental biology.”

Despite thinking he was set on this type of work, Omer still wondered what else was out there, so decided to do a rotation in a lab on the opposite end of the spectrum – cell type diversity in the nervous system. Here, Omer conducted a lot of cell and tissue work and became fascinated by the ability to observe and track cell type differentiation in the nervous system of fruit flies.

For his final rotation, Omer went on to look at development in the nematode worm, Caenorhabditis elegans – first sequenced here at Sanger in 1998. Omer knew his career as a developmental biologist was sealed when he witnessed the full spectrum of worm development from a single egg cell to a tiny worm.

“This is really the stuff that you see in a textbook diagram on development. This is real time; you are looking at it in your hands. I remember the moment I saw that, and I knew I was going to study development.”

Omer’s PhD thesis with Professor Chris Doe was characterising a poorly understood part of the fruit fly brain, where he identified a completely new genetic mechanism that expands cell type diversity during brain development. From this, Omer learned that a lot of development can be stereotyped and molecularly described – something he knew he wanted to apply to the human brain.

For his postdoc, Omer moved down to the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) which was considered, at the time, the best place in the world to do mammalian neural stem cell biology. His excitement is evident as he recalls some of the leading researchers in the field at the time, with whom he was able to cross paths, including Professor Arnold Kriegstein, who discovered the identity of mouse and human neural stem cells, and Professor Arturo Álvarez-Buylla, who discovered adult neurogenesis – the development of new neurons in the adult central nervous system.

Omer’s supervisor was Professor David Rowitch, a world expert on non-neuronal cells of the brain – glial cells – which were poorly understood at the time. Omer speaks fondly of David, explaining, “It would be hard to find someone who would say something negative about him.”

During his postdoc, Omer and his colleagues created a technique to map single cell gene expression and neural subtypes in situ. From this, they were able to come up with a new paradigm of how a very abundant class of glial cells, called astrocytes, could show such exquisite heterogeneity in the cerebral cortex. This not only provided insights into brain organisation and function, but also added something new to the picture that had not changed in over 100 years. This was a key step in Omer’s career that led him to where he is now, allowing him to recognise that these approaches could be used to dismantle the complexity of the nervous system in mammalian brains.

Halfway through Omer’s postdoc, David moved over to the University of Cambridge and asked if anyone wanted to join. Omer jumped at the chance and spent a year in Cambridge, setting up early versions of spatial transcriptomic technologies, which allow researchers to map gene expression within its native environment inside tissues.

While giving a talk, Omer was first introduced to Professor Sarah Teichmann, co-founder of the Human Cell Atlas and former Head of Cellular Genetics at Sanger, and Dr Sam Behjati, Paediatrician Scientist and Group Leader at Sanger. This then led to Omer collaborating on work with Sarah, generating spatial data of the decidua, a specialised layer of the endometrium. These data helped inform some of the biology of one of the first papers from the Human Cell Atlas, an international initiative which aims to create reference maps of all human cells as a basis for understanding human health and for diagnosing, monitoring and treating disease.

After a year, Omer moved back to the US to finish his postdoc but hit a crossroad. Despite loving his work, Omer started to see a lot of his peers publishing more papers and moving into faculty positions – none of which was happening for him. Omer had changed fields a few times, driven by the need to learn new things. He loved this, but also felt he was not making the right decisions professionally.

Then like clockwork, Sarah reached out to him with an opportunity to interview for a faculty position at the Sanger Institute working on spatial transcriptomics in human tissues. Despite lacking a postdoc paper and having a transition grant only good in the US, Omer thought this opportunity seemed too good to pass on and moved to the UK with his partner.

Since joining the Institute in 2018, Omer has been pivotal in the integration and application of spatial technologies. He has led the High Throughput Spatial Genomics (HTSG) initiative, an internal collaboration between faculty labs and core scientific teams to establish large-scale spatial data generation pipelines. These technologies, including one of the largest fleets of Xenium instruments in the world, are starting to be applied to many areas of Sanger science.

omer_GBM_xenium_cropped

Single cell resolution spatial map of tumour cell states in human glioblastoma, captured using Xenium technology. Image credit: Bayraktar Group/ Wellcome Sanger Institute

In addition to this experimental work, Omer’s team has also developed the widely used cell2location computational tool. This tool works like a GPS but for cells, pinpointing the locations of cell types within spatial data. This has enabled Omer and other collaborators to chart the human body from the reproductive system to the lung.

As part of his neurobiology research, Omer initially wanted to look at healthy brains. However, he realised that this type of work was already being done elsewhere, so decided to shift his focus to looking at brain conditions. Now, his team uses large-scale single cell and spatial transcriptomics, imaging and functional assays to study brain tumours, neurodegeneration and neurodevelopmental conditions.

“There's a really big concentration of incurable diseases in the brain. But my hope and vision is that if we apply the same playbook, we will be able to understand the rules of these diseases. So, what allowed us to understand the biology of the fruit fly nervous system, is the same lesson that allowed us to understand the biology of the mouse brain. This will hopefully be the same lesson that will allow us to understand how the normal human brain develops and how it dysfunctions in disease.”

Omer’s team has both strong computational and experimental skills, which allow his colleagues to understand complex single cell and spatial data. One of their key projects is studying glioblastoma (GBM), one of the most aggressive brain tumours. Despite being well studied, life expectancy for those diagnosed with this cancer is short, and effective treatment options are still limited.

2024-bayraktarlab1

The Bayraktar Lab team in 2024. Image credit: Bayraktar Group / Wellcome Sanger Institute

Over the past three years, supported by funding from Wellcome Leap, Omer and his team have been building the world's deepest multi-modal GBM Cell Atlas. They have leveraged all the different technologies including single nuclei RNA-ATAC-seq, Visium and Xenium spatial transcriptomics, spatial whole genome sequencing and others to take a holistic look at the biology of these brain tumours.

While findings are set to be published later this year, Omer explains that by using a combination of these different atlasing methods, they can unlock the complex heterogeneity of these tumours and provide an understanding of the fundamental biology of such brain conditions.

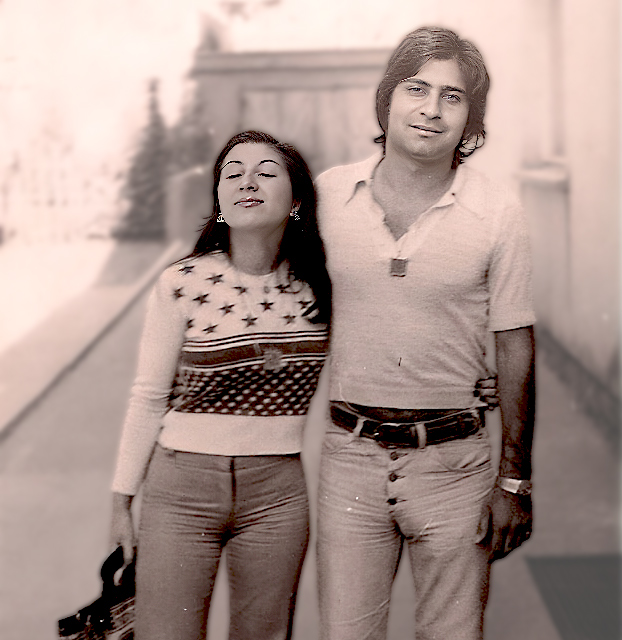

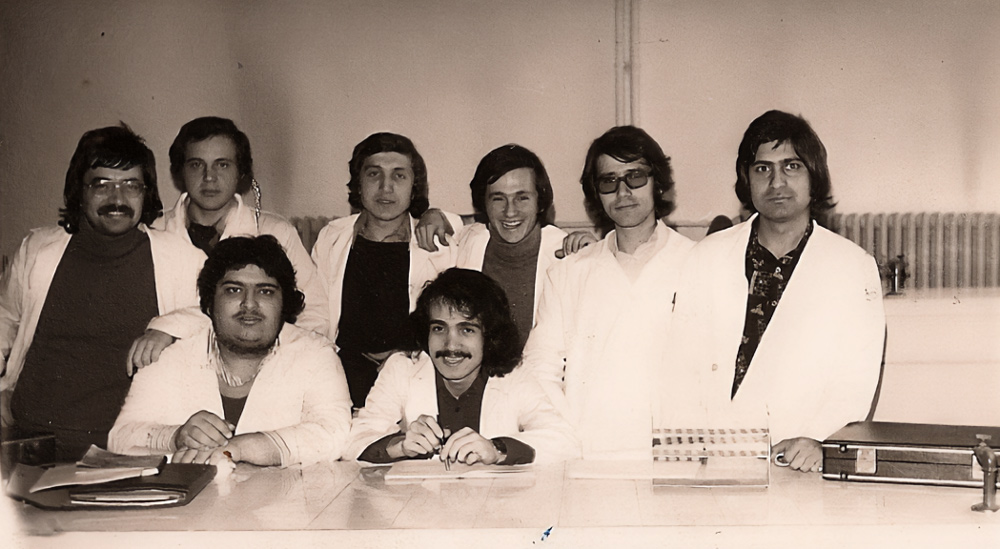

On a recent visit home to Turkey, Omer was given his father’s old, coloured histopathology atlas from his medical school days. Omer vividly describes the beauty of the book and all of the histological images of different tissues, emphasising how we can now see these same images but at single cell resolution and with transcriptomic context. This seems like an almost poetic link between both him and his father’s generation.

Omer's family memories. Clockwise from top left: Omer graduating from university, Omer and his parents at his graduation, Omer's mum and dad in together in the 1970s, Omer's dad studying to be a doctor (far right of photo), Omer's dad's old histopathology atlas, and childhood family time together. Image credits: Omer Bayraktar

Over the next two years, Omer’s goal is to apply these large-scale spatial pipelines to 30 to 40 human diseases to start building the Human Pan Pathology Atlas. Simultaneously, the team will also continue to push our understanding of human brain diseases, not only by releasing these atlases, but digging further into the molecular and cellular mechanisms that cancer cells exploit.

This in turn will lead to Omer’s third phase – the mechanistic phase. With the fundamental biology, uncovered by rich single cell and spatial datasets, the team can then begin to explore approaches to target these conditions.

“It becomes full circle. We went from a place where we were only looking at human tissue with histological tools, and now we are at a place where we are able to create these super rich molecular descriptions, which allow us to identify the fundamental rules and pathways. Now, we are coupling these to really targeted, functional analyses of the insights that show up in model systems like cell lines and organoids.”

Despite initial reservations about his professional decisions, Omer now reflects positively on his career trajectory.

“The way I work is inherently slow. I've changed fields every five years and this is the longest I've been in one field now. I think that's been an essential part of our success over the years, to be able to synthesise these different ways of thinking across biology, genomics, computational modelling and brain conditions. I think sometimes the only way is to just get in there. It's not good enough to have a collaborator that does it. Learning new things and getting into new things, from technologies to diseases to different approaches, takes time.

“The most important thing I got from Sanger was the opportunity to be slow, to be able to take risks, to go into brain tumours, which I knew nothing about three years ago. To have the intellectual space and luxury, and lack of existential funding fear, was amazing.”

“To also have the computational power and ways of thinking people have here, is great. I don't think my plan would have worked anywhere else. I was also incredibly lucky to recruit an amazing group of people to my team, they are the real heroes of my current chapter in science.”

Alongside raising two daughters under five with his wife, Leah, who is a specialist community health nurse, Omer enjoys travelling to visit his family when he can in both Turkey and the US. He sees a responsibility to share his values and learnings, not just with his children, but those he works with.

“My job in the lab, and at home too, is to impart what I think is fundamentally valuable, like a piece of my world view, and how I think about problems. But I also think it is important to let people develop their own ideas and tackle things on their own. I think to not micromanage is something I've struggled quite a bit with, and I still do struggle. I’m a work in progress. It's hard to let go, but it's also what people need, and I think it's what our kids will need too. My dad and mum didn’t tell me that they wouldn't pay or support me if I stayed in biology. They were cool with it.”

Despite staying in science, it is clear that Omer is still inspired by his early passion for literature as he talks of the need for serendipitous discoveries in research, rather than just the typical hypothesis-driven approach. He jokes how most of his projects were cobbled together when his “supervisors weren’t looking”. As such, over the next few years, as his team begins to transition from descriptive to translational work, Omer is hoping to encourage more breathing room and creativity that will allow him and his team to grow. But until then, it is back to work on his papers.

Find out more

- The Cellular Genomics programme web page is an informative resource to learn more about more research that is happening on campus.

- Dr Omer Bayraktar's profile page on the Sanger Institute website

- Explore the latest vacancies at the Wellcome Sanger Institute