Image credit: Benjamin Mueller

Enter the absorbing world of sponges, the intricate animals that have evolved to inhabit all corners of our Earth’s waterways and oceans. Thanks to a worldwide collaboration of sponge scientists through the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics project, which is led by the Wellcome Sanger Institute, more than 50 published high-quality sponge genomes and counting are now freely accessible to the research community.

Listen to this blog story:

Listen to "Enter the absorbing world of sponges" on Spreaker.

Squeeze into the world of sponge genomics

Imagine you are holding a sea sponge in your hand. At first glance, it appears to be nothing special, a simple lightweight, porous animal, mostly recognised as a household cleaning tool or something to use in the shower. Yet, hidden within the DNA of this humble organism is an evolutionary history that connects it directly to you.

Sponges are aquatic animals, not to be confused with the colourful polymer-based cleaning supplies stacked on our supermarket shelves. They mostly live in the ocean but can also be found in freshwater and estuaries – the places where sea and freshwater meet.

Today, scientists can study sponge genomes by sequencing every letter of their genetic code. This can reveal previously unknown evolutionary histories and help us better understand how sponges thrive thanks to symbiosis. Symbiosis is a broad term that applies to a mutually beneficial relationship between organisms in close association.

Researchers are studying sponge genomes and their symbionts in the Sanger Institute-led Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics (ASG) project. This project has thus far delivered over 50 sponge genomes in addition to genomic data on thousands of associated microbial symbionts with these numbers continuing to grow. In this blog, we will share researcher stories that might blow your expectations of what these ‘simple’ sponges can do, right out of the water.

Sponges: A brief history

Sponges and their symbionts are wonderfully diverse. Some sponges can make glass, some are farmed and used in the beauty industry, while others boast interesting microbial and chemical diversity. But you may be asking yourself, what exactly is a sponge?

Sponges are animals. We know that sponges are the oldest living Metazoans – complex animals – that diverged during the Precambrian era – the earliest part of Earth’s history – making them millions of years older than dinosaurs. This begs the question – are we all essentially sponges? In recent years, new sponge sequences have revealed our shared molecular heritage with some of Earth's earliest animals.

Sponges evolved in the Precambrian period, approximately 800 million years ago during Earth’s earliest history. Image credit: LadyofHats, Wikimedia Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain.

A lot has changed since then, with various species – including the aforementioned dinosaurs – having come and gone. So, how have these ancient creatures established themselves worldwide and survived so long? Well, sponges are survival experts, able to adapt to almost any environmental condition they find themselves in. It is these skills, along with some other surprising abilities, that have attracted the attention of scientists from all around the world to study the impressive, but often underestimated, sponge.

The ASG project was established 2019 to provide new tools and resources to enable the study of aquatic symbiosis. Sponges are lived in and on by symbionts, but the details of those relationships are poorly understood. Most symbionts cannot be grown in a lab and sponges are tricky to maintain in aquaria.

However, genome sequencing provides an alternate approach. Genomics can help researchers define the different sets of organisms involved in sponge-microbe symbiosis. It can also reveal how symbiotic relationships arose, how they are stably maintained and how they contribute to major biogeochemical cycles in the Earth’s oceans. An international team of researchers, including those at the Sanger Institute, have been working together through the ASG project to tackle the methodological challenges in sponge symbiosis research, and interpret the new glut of sponge and symbiont genome sequence data.

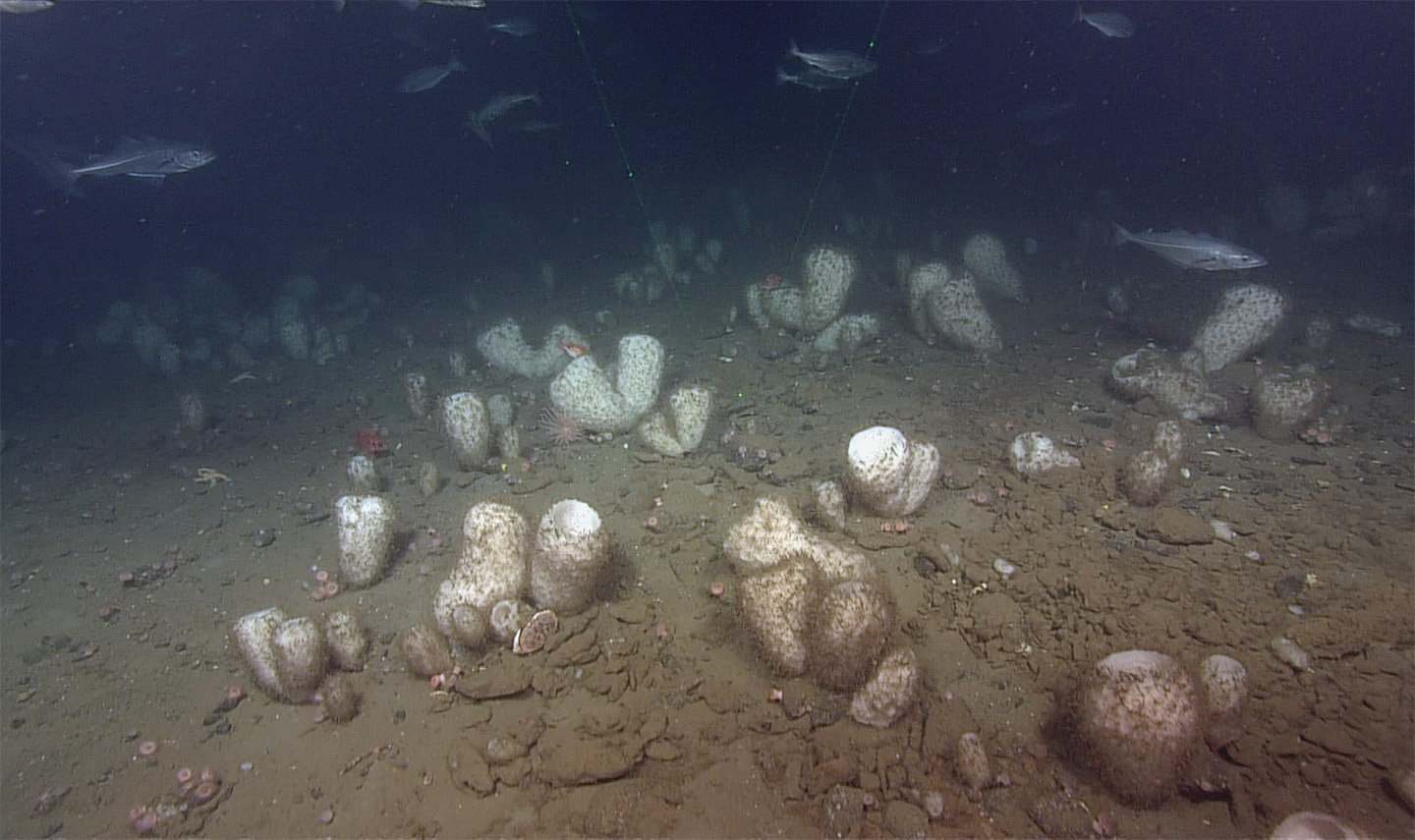

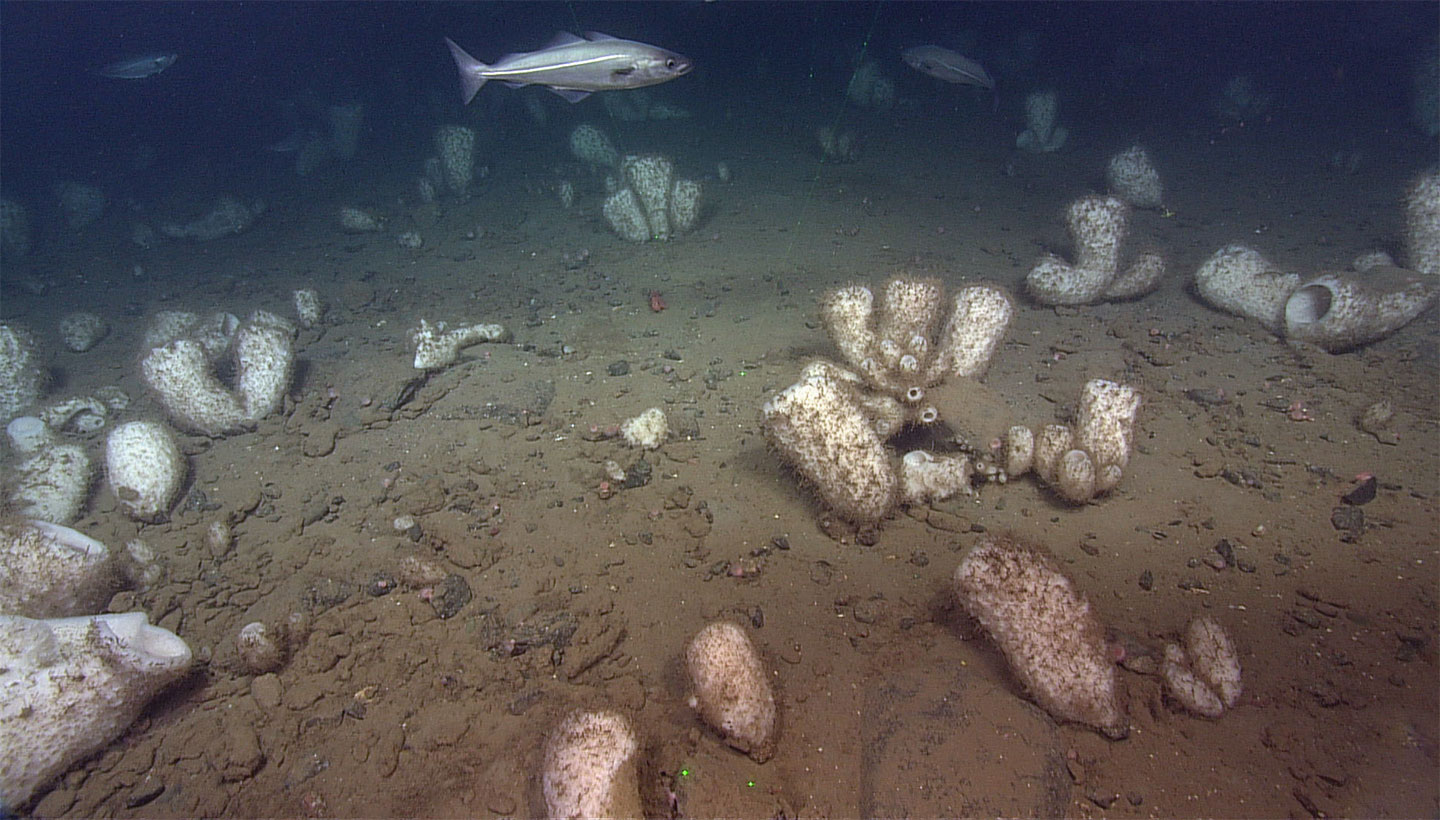

A variety of deep sea glass sponges. Image credit: Julian Gutt/Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research

Why are sponges important?

Through sponges, unique habitats are formed that provide shelter, breeding sites and unique chemical environments that allow life to flourish in often inhospitable locations. Sponges unequivocally play an important ecological role in nature. From the darkest of deep seas to the shallows of reefs and freshwater lakes, sponges act as ecological hotspots. And, unlike corals, you can find them thriving pretty much everywhere.

We know sponges are a rich source of natural products. Thousands of chemical compounds have been recovered from this animal phylum alone, making it the richest source of new potential pharmaceutical compounds in the world’s oceans and lakes. The compounds that sponges and their symbionts produce could serve as templates for future drug discovery. This untapped potential for discovery makes the availability of new sponge genomes even more exciting.

Sponges in the genomics era

There historically has been a dearth of genomic information for sponges. Then, 15 years ago, the first key piece of work to sequence sponge genomes was led by evolutionary biologists and Drs Sandie and Bernard Degnan at the University of Queensland, Australia. They sequenced the genome of Amphimedon queenslandica, a sponge native to the Great Barrier Reef. The Degnans were the first in their field to apply molecular techniques to study sponges and symbiosis, laying the foundations for sponge genomics.

“The first, and for a long time only, sponge genome was published 15 years ago. Our pioneering international effort was supported by the US Department of Energy’s Joint Genome and provided an exciting new perspective on the evolutionary origin of animal complexity”.

Sandie Degnan,

Professor, University of Queensland, Australia

“The recent completion of more than 50 sponge genomes and counting via the ASG project will significantly extend these original insights, revealing ancient principles underlying the genomic regulation of animal-microbe symbioses.”

Bernard Degnan,

Professor, University of Queensland, Australia

These images show: (top left) an adult Amphimedon queenslandica inside a coral. Image credit: Dr Marie-Emilie Gauthier; (top right) an internal brood chamber with various developmental stages visible. Image credit: Dr Gemma Richards; (bottom) the intertidal reef flat habitat of this species on Heron Reef, southern Great Barrier Reef (named Shark Bay). Image credit: Dr Marcin Adamski

A lot has changed since the first sponge genome, and the ASG sponge sequencing project has built upon the Degnans’ legacy. The new ASG sponge and symbiont genomes enable researchers to perform powerful comparative analyses, interrogating the content and organisation of the genomes with the sponges’ relationships, lifestyles and microbiome compositions.

Below, we provide several case studies where sponge genomes have been used by the ASG sponge community to more deeply understand symbioses.

Sponges are ecologically important

Despite the stresses of climate change, sponges seem to be doing well. Their ability to form intricate symbiotic relationships, which help produce useful chemical compounds and support coral reefs, is just one of the reasons that sponge research continues to drive forward.

Thanks to the availability of high-quality whole genomes produced by the ASG project, researchers can continue to understand the fundamental biology of these sponges that may have implications for future drug discovery, conservation efforts and much more.

New genomes for the sponge research will continue to have an amplifying effect on the field and enable preliminary studies that could support future funding opportunities. The ASG project and the sponge community will ensure collaborations born from, or assisted by the ASG project, will continue to benefit and grow research partnerships.

For a full description of each image, please click on the image to view at fullscreen size.

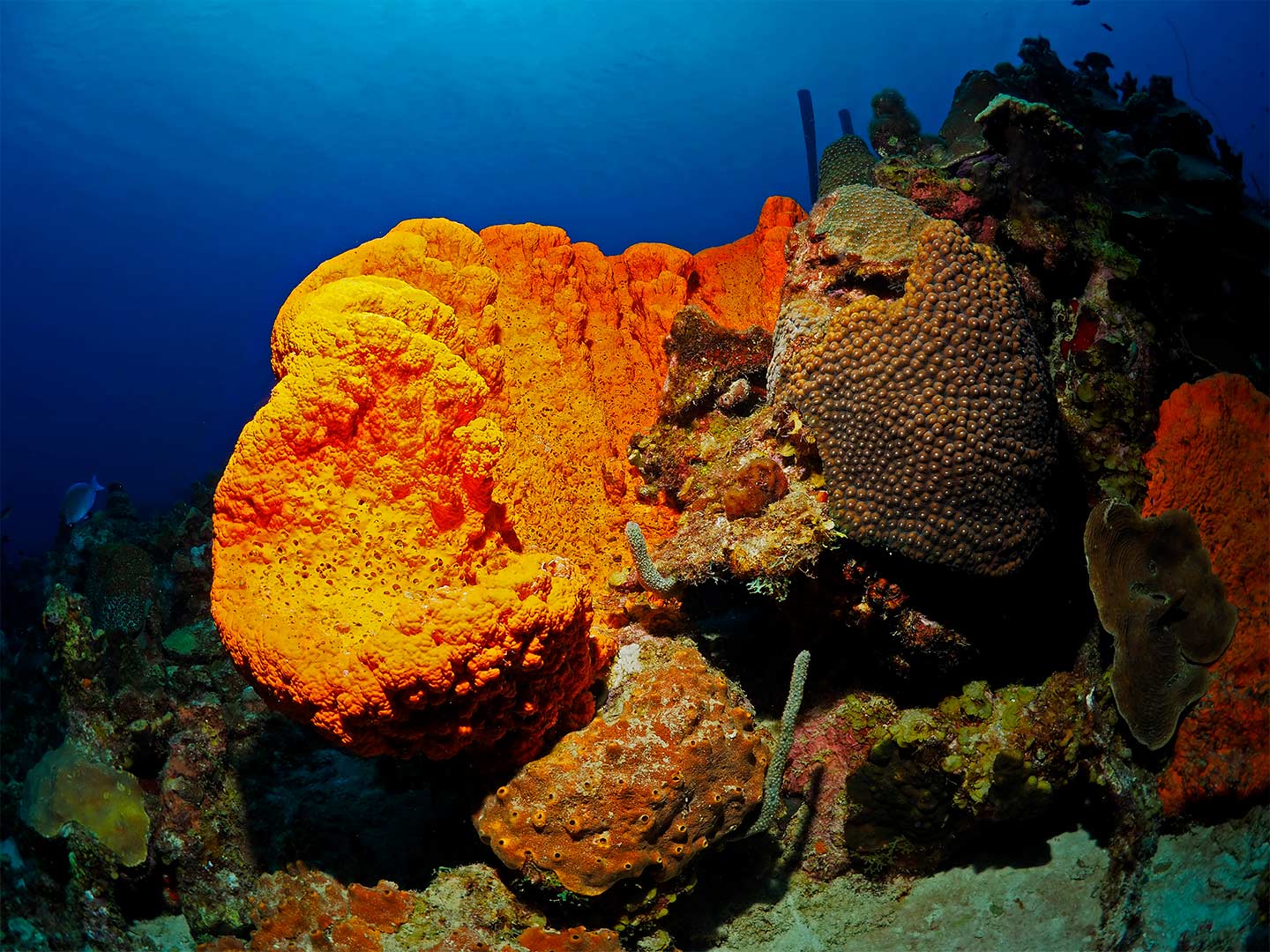

Encrusting sponges hidden in caves, overhangs and cavities under the reef can make up >30% of the entire benthic biomass on the reefs. Image Credits: Benjamin Mueller

There are over 7,000 species of sponges. Researchers studying these amazing animals have a bright future ahead as they incorporate genomics to inform population genetics, restoration efforts and conservation management strategies aimed to protect and understand these creatures for the future. In this UN decade of ecosystem restoration, sponges will be considered an important element in preserving and restoring many of the plethora of ecosystems that they inhabit.

So, the next time you have a shower or watch an episode of SpongeBob SquarePants, soak it up because sponges are here to stay.

This work was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through a grant (GBMF8897) to the Wellcome Sanger Institute to support the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics (ASG) project.

Find out more

- Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics (ASG) project

- Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

- Professor Ute Hentschel Humeida at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research

- Tree of Life programme at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

- Published protocols from the Sanger Institute's Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics Core Laboratory team