Coral genomes to combat bleaching

Corals are bleaching at unprecedented rates due to human-induced climate change. Researchers studying the DNA of corals and the algae they live in symbiosis with aim to better understand how to protect them.

Story by Carmen Denman Hume.

19 September 2024

Background image: Professor Michael Sweet at the University of Derby studying coral biology and the use of environmental DNA to describe the distribution of rare, endangered or invasive species in freshwater and marine ecosystems. Credit: Morgan Bennet Smith

Listen to this blog:

Why protect corals?

Imagine the ocean, teaming with life. Now imagine that vast ocean, but completely empty. A frightening thought?

Coral reefs are the rainforests of the ocean: biodiverse hotspots that are critically important for global ecosystems. However, sadly, warmer temperatures are now bleaching our planet’s corals, at an alarming rate, and placing these fragile ecosystems in grave danger.

Coral reefs are living structures, supporting 25 per cent of marine life despite covering less than 1 per cent of Earth’s surface. According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, our coral reefs are valued at $2.7 trillion USD annually1. Furthermore, over one billion people depend on reefs as a food source. Yet as has been widely reported, coral reefs worldwide are suffering the consequences of human-induced climate change and the after-effects of other more local stressors. With startling images and statistics in the headlines on a daily basis, many people wonder what can be done to help.

Enter coral reef researchers. To help tackle this challenge (as well as boost research into the biology of aquatic species), researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Derby and other collaborators associated with the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics (ASG) Project are sequencing corals and symbiotic algae (symbionts) to produce high-quality reference genomes. The ASG Project was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the data generated is released openly and accessible to anyone via the European Nucleotide Archive.

Funded research initiatives such as the ASG Project mean collaborative communities of researchers can analyse large volumes of carefully curated data and advance basic biological understanding which in turn will inform conservation and protection of our planet’s coral reefs.

The coral and algal symbiont work is however only a part of the ASG Project. Indeed efforts to sequence the genomes of a wide diversity of creatures from sponges, to jellyfish and even single-celled eukaryotes known as protists. These species are all essential to ecosystems around the world and yet little is known about their DNA and how their symbiotic way of life has come to be.

Intrinsic to the ASG Project design is for its data to be a resource for all. DNA sequencing data from the ASG Project is made freely available via databases and open access Wellcome Open Research publications. The ASG project will be well-equipped to answer key questions about the ecology and evolution of symbiosis in marine and freshwater species.

The worldwide race to sequence corals and save their symbionts

Coral reefs are in rapid decline on a global scale. It is estimated that by as early as 2030, 90 per cent of reefs will become functionally extinct2. The coral animals that make up a reef live in symbioses with algae Symbiodiniaceae or zooxanthellae. Without its symbiotic algae, coral animals would not be able to harvest sunlight for energy. These tiny algal symbionts actually produce upwards of 80 per cent of the coral host’s energy needs.

coral-polyps-symbionts-symbiosis

Illustration of a coral animal, where the symbionts Zooxantellae are shown to be living in the tissues of the animal. Image credit: OIST (Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, 沖縄科学技術大学院大学). Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

When stressed, corals will often evict their algal partners, a process called coral bleaching and sadly this is becoming more and more common as oceans warm due to global warming. The ‘bleaching’ effect is actually observable to the naked eye – coral tissue without symbionts become translucent and you can see the white calcium carbonate skeleton beneath.

What is coral bleaching?

Healthy coral

Coral and algae depend on each other to survive.

Corals have a symbiotic relationship with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae that live in their tissues. These algae are the coral’s primary food source and give them their colour.

Stressed coral

If stressed, algae leaves the coral.

When the symbiotic relationship becomes stressed due to increased ocean temperature or pollution, the algae leave the coral’s tissue.

Bleached coral

Coral is left bleached and vulnerable.

Without the algae, the coral loses its major source of food, turns white or very pale, and is more susceptible to disease.

Stages of Coral Bleaching diagram based on an image from NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program’s What is Coral Bleaching? webpage

Studies to better understand this coral-algal relationship are urgently needed to protect corals for the future. The ASG Project is a relatively small research collective, tasked with a big challenge – sequence and assemble the genomes of the marine and aquatic species that form symbioses. Often, little about the genetic makeup of these species is known – this includes some of the world’s most enigmatic corals, such as the most important and endangered species in the Caribbean, the staghorn coral, whose decline is a visible symbol of global heating.

Corals are currently experiencing the hottest sea temperatures ever recorded and, in fact, we are in the midst of the fourth recorded mass global coral bleaching event. Indeed, we keep hitting the wrong kind of records, month on month from Ireland to the Antarctic.

For example, in Florida, waters reached 38.3°C in July 20233 and the Mediterranean Sea recorded 28.7°C in June of the same year4. Both are all-time highs. Most corals comfortably live below these thresholds and will experience stress and bleaching when these temperature thresholds are broken.

Background image: Staghorn coral. Credit: Professor Michael Sweet / University of Derby

Gathering samples to generate gold-standard genomes

The ASG Project is producing high-quality genome sequences to enable coral scientists to access a wealth of data to shape their morphological and molecular studies. Over the last few years, a team of experts have been collecting and compiling samples of corals (and their symbionts) from around the world. After collection, the samples are sent to the Sanger Institute.

Although most corals and their symbionts were wild samples submitted for DNA sequencing by scientists based in countries around the world, there are aquaria cultured corals and symbionts included in sequencing efforts too.

Staghorn coral being grown

Professor Michael Sweet examining staghorn coral being grown at the University of Derby. Image credit: Professor Michael Sweet / University of Derby

Professor Michael Sweet, at the University of Derby, leads the ‘Coral symbiosis sensitivity to environmental change hub’ under the ASG Project. He says: “The generation of gold-standard genome sequences for coral animal hosts and their associated symbionts is an unprecedented resource to the coral community.” Prior to undertaking any sequencing work, Michael and colleagues reached out directly to the coral community to find out what species were most important for them. This grassroots-style feedback mobilised the coral community to raise requests they saw as most important to address using DNA sequencing.

Further, Michael and the team, ensured (where possible), corals were collected from the reefs where the type specimen was originally sampled. These corals were then compared to the skeletal samples housed in museums, a process which ensures taxonomic classifications were as accurate as possible prior to DNA sequencing.

Interactive world map of coral samples sequenced by the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics project as of 1 June 2024

Use the zoom tool (bottom left) to expand areas to see the individual samples. Click on the icons to see the information for each coral.

Background image: Professor Michael Sweet examining staghorn coral being grown at the University of Derby. Image credit: Professor Michael Sweet / University of Derby

Cracking open corals and their algae

Aquatic and marine species with their symbionts are notoriously tricky to produce genomes for, as they are so intertwined.

Once the coral samples are selected, collected and shipped to the ASG Project sample team at the Sanger Institute, their DNA is extracted for sequencing. After trialling different methods, the team extracts coral DNA by taking corals from dry ice into tubes with magnetic zirconium beads for bead beating the sample, which, as it sounds, involves shaking the sample and magnetic beads at a high speed so that the beads crush the coral into a fine powder.

Senior Research Assistant at the Sanger Institute, Dr. Graeme Oatley, says: “One of the big challenges of extracting DNA from corals has been in disrupting hard stony corals into a fine powder, which is crucial if we are going to be able to extract sufficient, high quality DNA.”

This improved process means that DNA can be extracted in long stretches – enough to generate high-quality, long-read data using the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) DNA sequencing system.

Coral sample preparation and DNA extraction techniques at the Sanger Institute have been a learning process. Usually, coral sperm is sent for sequencing, which excludes the need for dealing with the hard stony coral exoskeleton. However, the team were able to develop new expertise and methods to take the whole coral animal, regardless of contaminants and symbionts, and proceed through to DNA sequencing. This methodology is publicly available and can be taken on board by other researchers interested in sequencing corals.

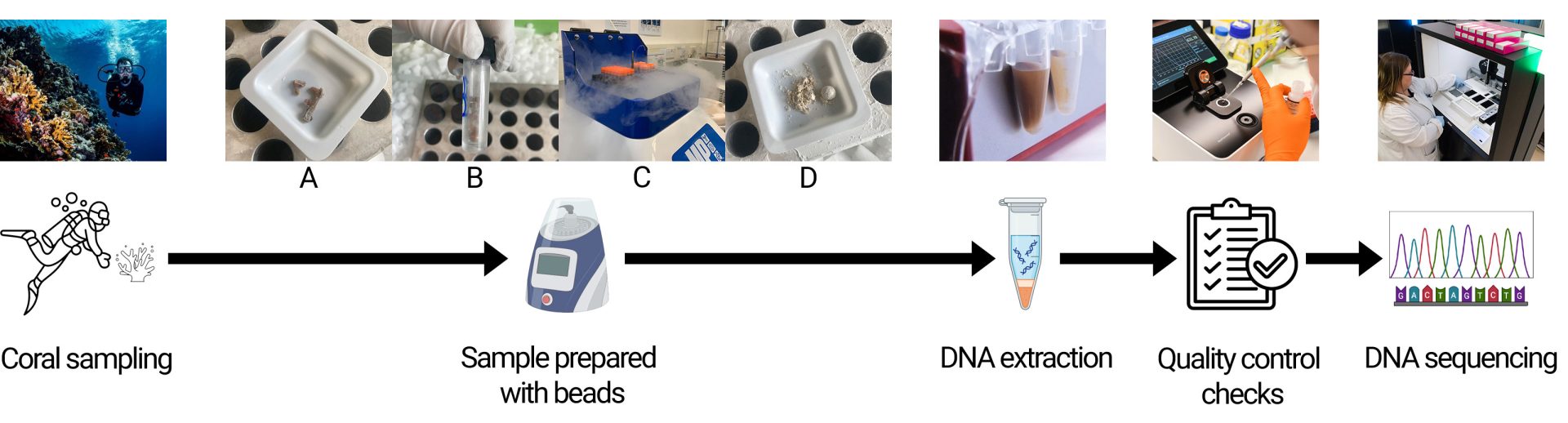

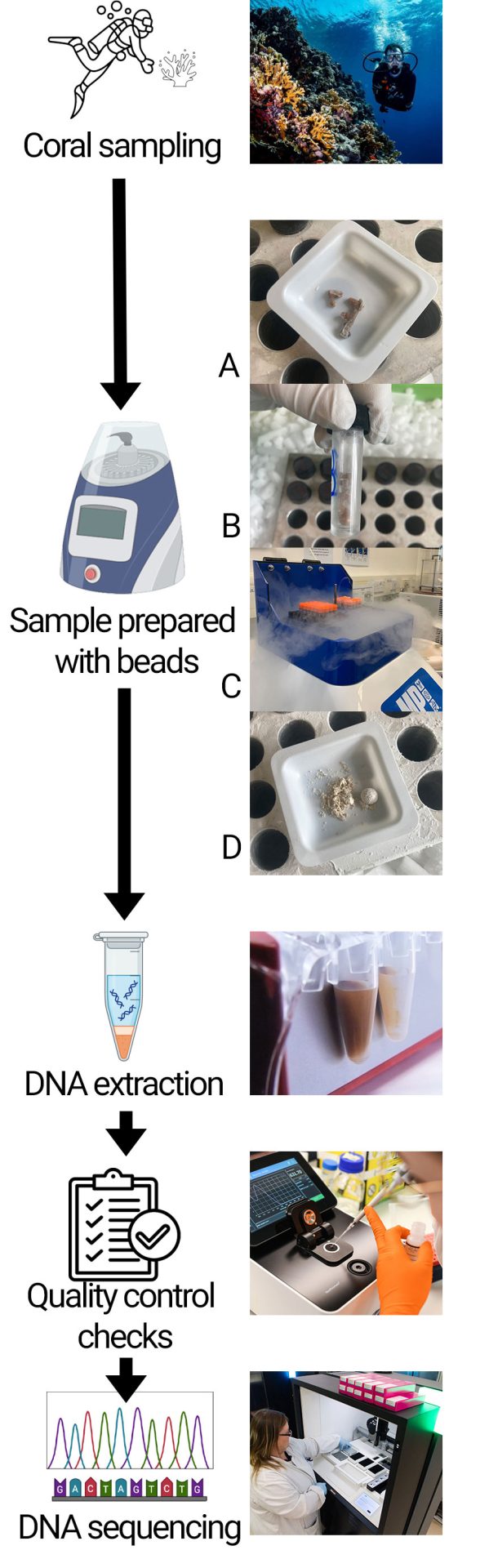

How to build a high-quality coral genome

Coral sample preparation and sequencing: Coral collection, preparation by the Sanger Institute’s Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics sample team using beads in steps A-D, DNA extraction Quality Control, and DNA sequencing. Image credits: see listing at end of the article.

How the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics Project sample team at the Sanger Institute prepares coral samples for DNA sequencing

Step A. Coral specimen before bead beating. Step B. Coral specimen and zirconium beads in a bead beating tube. Step C. Coral samples loaded onto the FastPrep® 96 bead beating instrument. Step D. Coral specimen after bead beating, disrupted into a fine power ready for DNA sequencing.

Piecing coral genomes back together using DNA sequence analysis and assembly

Once the DNA sequence is obtained for a coral or symbiont, the bioinformaticians get to work. Raw data from the DNA sequencing machines arrive in fragments, and so these are computationally pieced together, or assembled, into a full genome, using customised algorithms. Once data are ready, they are rapidly made freely available to researchers worldwide.

Dr. Noah Gettle, Senior Bioinformatician at the Sanger Institute, the coral-symbiosis sequencing analysis has been trickier than expected. “The main challenge in sequencing and assembling these [coral and symbiont] communities lies with the corals’ photosynthetic partners, the dinoflagellate Symbiodinium. The Symbiodinium are single-celled organisms, but are far from simple. They can have genomes that are two to three times the size of their host often with fewer cells in a given sample, and have their genome packed in bizarre ways that can make DNA extraction difficult.”

Genome Comparisons of coral and algae genomes

Comparison of coral and symbiont genome sizes (in Gigabase pairs or Gbp). Image credit: Mark Thomson / Wellcome Sanger Institute

As a result, when extracting DNA and preparing it for downstream DNA sequencing, often very little Symbiodinium material is obtained relative to the coral host. This then impacts the amount of data available to use to assemble the coral and symbiont genomes.

Background image: Pulverised coral in preparation for DNA extraction and genome sequencing. Credit: Elizabeth Sinclair / Wellcome Sanger Institute

The case of the Staghorn Coral

One of the corals sequenced as part of the ASG Project is the iconic Acropora cervicornis, known as the Staghorn Coral.

Staghorn Coral is one of the most important corals in the Caribbean reefs, contributing to the reef’s build-up over the last 5,000 years. Staghorn Coral can grow in dense groups in very shallow water and can create an important protective habitat for reef animals, especially fish. Staghorn Corals are critically endangered and focus has turned to coral restoration in an effort to identify ways to help these corals enhance their resilience to survive increasingly stressful conditions, such as our oceans warming.

Serena_Hackerott with staghorn coral

Background image: Dr. Serena Hackerott with staghorn corals collected in collaboration with the Coral Restoration Foundation for her stress hardening experiment, funded by the NOAA Ruth Gates Restoration Innovation Grant program. Photo credit: Zachary Howard

Coral researcher Dr. Serena Hackerott was studying staghorn corals at Florida International University where she carried out her doctoral research project investigating the ability of staghorn corals to adapt to heat stress. She studied coral adaptation by ‘hardening’ staghorn corals to future ocean temperatures, much like horticulturists harden-off plants to different conditions on land.

One main objective to the staghorn coral stress exposures was to characterise the genes that are switched on or off, or stay the same, in response to heat stress. The aim was to determine if the heat-stress hardened coral was better equipped at a genetic level to survive stress in the future. Serena is particularly interested in epigenetic changes that impact how a coral switches on and off genes in response to different environmental conditions.

In this laboratory work, Serena wanted to describe the cellular functions involved in priming a coral to heat-stress, but she could not complete this work without a reference genome. Now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Delaware, Serena and her colleagues in the Eirin-Lopez Environmental Epigenetics Lab will utilise the high-quality reference genome generated by the ASG Project to explore how stress hardening changes gene regulation in corals.

Serena adds: “Genomic resources and research will be vital to inform the effective application of coral conservation interventions such as stress hardening and assisted evolution. The genome of Acropora cervicornis will be of particular importance as this critically endangered species is the focus of many coral restoration efforts that could benefit from strategies to enhance resilience.”

The ASG Project has effectively sequenced the whole genome of the Staghorn Coral around 240 times (termed 240X coverage). At higher levels of coverage, each base has a greater number of sequence reads to align next or and/or against each other, so base calls can be made with a higher degree of confidence. However, the DNA sequencing of the Staghorn Coral’s symbiont proved a little trickier.

Scientists are having difficulty getting sufficient DNA to assemble the genome for the Staghorn Coral’s Symbiodinium partner. To make matters more interesting, the large Symbiodinium genome appears to be composed of lots of repetitive DNA and arranged into more than 50 chromosomes, which standard assembly algorithms have difficulty with.

Comparison of number of chromosomes in the coral (28) and symbiont (50) genomes.

Bioinformatics expert, Noah says: “The difficulty in assembling these genomes means there is only one good reference assembly for all dinoflagellates (the group containing Symbiodinium). Although challenging, assembling these genomes will be worth the fight as they will open brand-new avenues for aquatic symbiosis research for years to come.”

Background image: Dr. Serena Hackerott with staghorn corals collected in collaboration with the Coral Restoration Foundation for her stress hardening experiment, funded by the NOAA Ruth Gates Restoration Innovation Grant program. Photo credit: Zachary Howard

Coral collaboration and conservation

Coral reef scientists around the world have called for collaboration and the development of tools to help save coral reefs – the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics project is answering this call, with research ongoing. For example, genome sequences and methods to improve the study of coral genomes can provide valuable information for disease research and population genetics.

The generation of high-quality genome sequences from a wide range of symbiotic systems will merge the decades of ecological, evolutionary, taxonomic, and experimental expertise of researchers from diverse backgrounds, with the Sanger Institute and partners like the University of Derby ensuring all data is accessible. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation funding has allowed the ASG Project to lay the genomic foundations for scientists so they can answer key questions about the ecology and evolution of symbiosis in marine and freshwater species.

Background image: A thicket of staghorn coral. Credit: Serena Hackerott / FIU

A look to the future for symbiosis research

The ground breaking ASG Project is providing new technology and freely available methods that can be applied to help safeguard the future of aquatic organisms around the world.

There is still much to be done. The ASG Project is sequencing the DNA of other organisms living in symbiosis. Jellyfish, sponges, and protists for example, together with the microbes they live with. The data will be released openly to benefit all who work on symbiosis, from conservation geneticists to those interested in the origin of the eukaryotic cell. This research certainly propels coral research further into the genomic era.

Background image: Jellyfish. Image credit: Morgan Bennett Smith

Find out more

- Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics (ASG) Project

- Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

- Professor Michael Sweet, at the University of Derby

- Dr. Noah Gettle, at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

- Dr. Serena Hackerott at Florida International University

- Eirin-Lopez Environmental Epigenetics Lab

- Tree of Life Programme at the Wellcome Sanger Institute

- Interactive world map of coral samples sequenced by the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics project as of 1 June 2024

- Published protocols from the Sanger Institute’s Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics sample team

References

- Crucial $2.7 Trillion Resource Is Being Lost to Warming Ocean Temperatures. Past Chronicle website.

- 99% of coral reefs could disappear if we don’t slash emissions this decade, alarming new study shows. World Economic Forum website.

- Extreme Ocean Temperatures Are Affecting Florida’s Coral Reef. National Environmental Satellite Data, and Information Service. NOAA website.

- Mediterranean Heat Waves Monitoring Service web page. Copernicus Marine Service website.

Image credits for How to build a high-quality coral genome

- Morgan Bennet Smith

- Jessie Jay / Wellcome Sanger Institute

- Greg Moss / Wellcome Sanger Institute

- Elizabeth Sinclair / Wellcome Sanger Institute

- Mark Thomson / Wellcome Sanger Institute